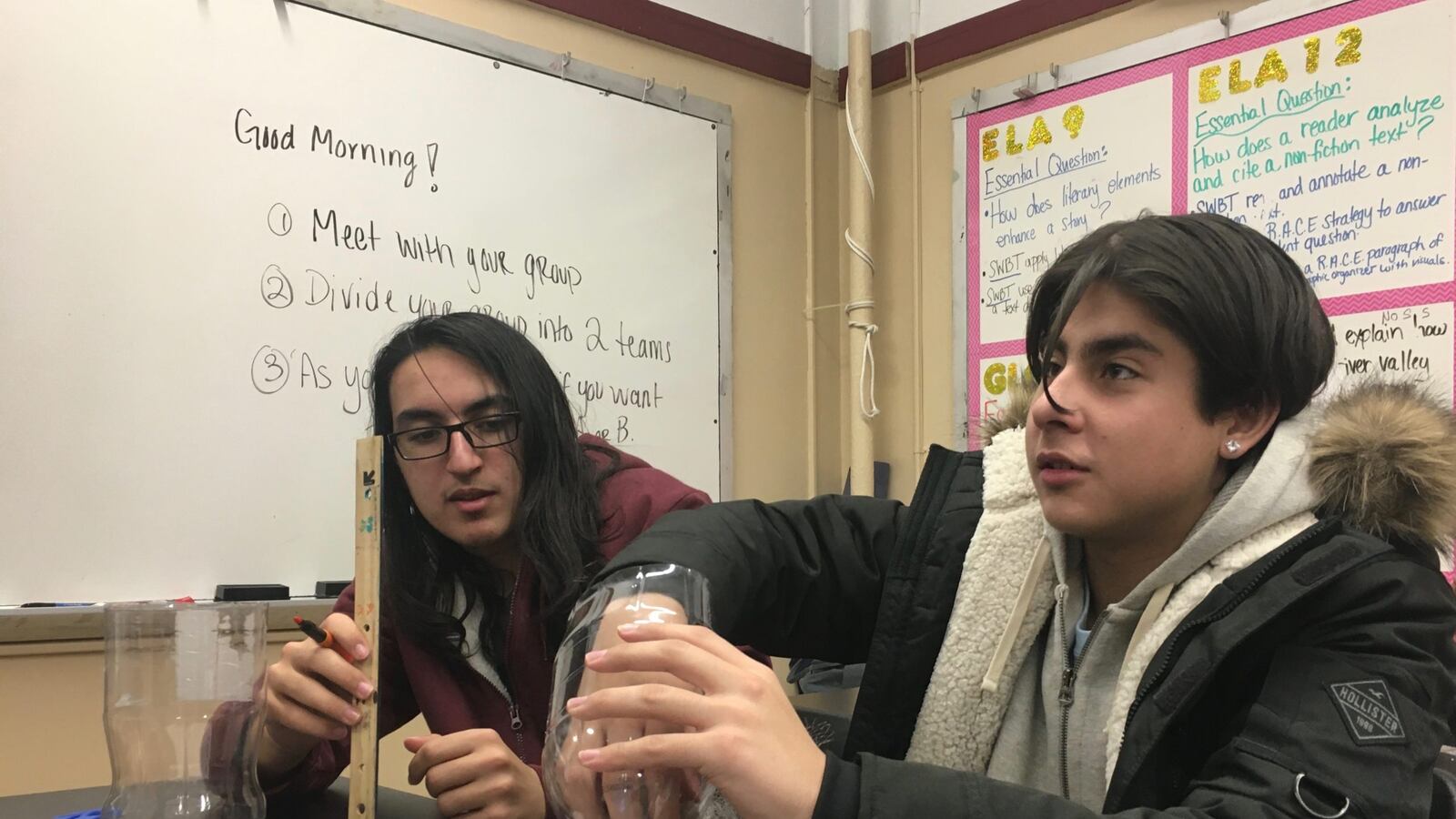

Students in a horticulture class at Veritas Academy in Queens were scooping soil into plastic soda bottles with sawed-off bottoms, creating mini-ecosystems with layers for plants, compost, and a small fish.

The idea to pursue this multi-week project wasn’t solely dictated by Vittoria Venuti, the teacher shuttling around the classroom that recent morning. This science elective had grown out of overwhelming student interest, and students themselves had a direct say in choosing to experiment with creating small-scale ecosystems.

“I’m so used to lessons given to us,” said Jennifer Gallego, a senior at Veritas who helped push for the horticulture elective. “This is kind of a break where we get to say what we want to do.”

The Flushing high school is laser-focused on finding ways to unearth the gifts and talents of its students.

To do so, Veritas is one of several schools across the city that have embraced a “Schoolwide Enrichment Model.” The approach emphasizes that students of various ability levels should receive high-level, hands-on, project-based instruction — not just those labeled “gifted and talented.” Educators develop projects based on their students’ interests.

The school’s model is at the heart of a broader debate in New York City education about whether students at different academic levels should be served in the same classrooms.

A high-level mayoral task force grappling with how to bolster school diversity has called for rapidly scaling up similar enrichment approaches as a replacement for gifted and talented programs. Elementary school gifted programs, which generally admit students on the basis of a single test given to 4-year-olds, tend to be disproportionately white and Asian.

When it comes to tackling high school segregation, some activists and experts are pushing the city to scale back or overhaul “screened” admissions that choose students based on grades, test scores, and attendance. These schools also tend to be starkly segregated by race, class, and previous academic performance.

Such changes remain controversial. Many families and advocates argue that maintaining programs that track students by ability are essential to ensure that academically advanced students are adequately challenged.

‘Less about measuring students’

Officials at Veritas see their program as a proof point that selective admissions aren’t necessary to offer academically rigorous classes. The school offers priority to students in Queens, but does not admit students based on their academic records. The school’s student body is 61% Hispanic, 13% Asian, 13% black, and 9% white. Nearly 69% of families come from low-income families, roughly in line with the district average.

“Our opinion has always been put [school-wide enrichment] in every school because that way you address every child,” said Cheryl Quatrano, a co-founder of Veritas, who retired last month. She also helped launch a Bayside middle school that uses a similar model.

In the horticulture class, for instance, students who are still learning English participate alongside their peers. When students break out into groups for activities like the ecosystem project, Venuti said she makes sure students aren’t simply clustered by ability.

“They have to be successful as a team,” Venuti said, noting that students will sometimes serve as de facto translators for each other to make sure the task at hand is clear to everyone in the group.

To dig deeper into students’ interests and help shape the school’s battery of electives, Veritas deploys regular surveys that ask dozens of questions about student learning styles, interests, and even their degree of motivation. One of them is adapted from a questionnaire developed by Joseph Renzulli and Sally Reis, academics at the University of Connecticut who helped pioneer the Schoolwide Enrichment Model.

“It’s much less about measuring students,” Reis said of their approach. “We’re trying to create the conditions in which interest develops.”

Still, despite a weeklong training teachers attend when they first arrive, some said it can be a big learning curve to tailor their classes to hew with student interests.

“There are so many different ideas. How do you incorporate this hands-on model, student choice?” Venuti said. “Planning the lessons we do takes a long time.”

Following teacher interests, too

In addition to taking student interests into account, Quatrano emphasized that it’s important to give educators an outlet for their passion projects.

Based on his lifelong passion for superheroes, social studies teacher Laurence Neadel created a contemporary mythology class where students draw parallels between Star Wars and ancient Greek and Roman myths, as well as design extraterrestrial species and invent biological explanations for how they would survive.

While the school offers Advanced Placement classes typically designed for students who are ready for more accelerated work, Veritas takes a more flexible approach. In one case, a student with a disability advocated for enrolling in AP Psychology, a request the school accommodated. That prompted several other students with disabilities to ask about taking AP classes, according to the school’s quality review.

“I love the fact that we’re giving more chances for students to come in and take those more rigorous courses,” said Matt Gill, who teaches AP computer science.

Providing access is more important than whether students get top scores on the AP exams, he said.

School officials also emphasized that they work hard to get to know students and hold regular meetings to get a handle on any social emotional issues that may crop up and which can affect a student’s attendance or overall school performance.

In a recent meeting of the school’s “social emotional inquiry team,” school social worker Hal Eisenberg led a conversation with a group of teachers about students they were worried about. One student was struggling with a parent’s negative reaction after coming out as bisexual. Another, who often misses class, was wrestling with being the de facto caretaker for an autistic brother. One was dealing with a mother’s terminal illness.

After each discussion, a handful of assembled teachers offered their insights into what was going on with each student, offering up strategies to help them.

A model to replicate?

Still, there are some signs that the school has room for improvement. Only about half of the students said they were challenged in their classes, according to the education department’s annual survey from last year. That figure was slightly lower than the city and borough averages.

“That’s something we’re aware of and is a constant conversation here,” Eisenberg said of the survey responses. “We’re always, always looking at curriculum.” School officials added that they believe some students may have misinterpreted the question.

It remains unclear whether Veritas’ schoolwide enrichment model will be implemented more widely in New York City. Mayor Bill de Blasio has indicated he won’t be making any decisions about gifted and talented programs this year and has been reluctant to implement sweeping changes to selective high schools.

Still, Matt Gonzales, a member of the advisory group that recommended expanding schoolwide enrichment, says he is hopeful the model will catch on, emphasizing that there are many different ways for schools to incorporate it.

“There’s not necessarily one way to lay this out across the system,” he said. “Veritas is one of the standards of what we should be thinking about.”