This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Pamela James was thrilled when her granddaughter was accepted at Franklin Towne Charter High School. Her granddaughter raced off to tell friends the good news, and James gave the school a copy of her granddaughter’s Individual Education Program (IEP), which included the need for emotional support — a common but relatively expensive requirement among students in Philadelphia schools.

Hours later, they were both shaken when James got a call from the Northeast Philadelphia school, informing her that her granddaughter could not attend as a result of her emotional disturbance diagnosis, that the class she needed was “full,” and that the school would not accommodate her.

“After I took her IEP to the school, that’s when they shot me down,” James said. “That was really ugly discrimination.”

James was furious. No one at the school would return her calls, though she eventually received a brief letter restating that her daughter could not attend.

“I don’t understand how they’re able to do this,” James said. “They decided to change their mind because she needed emotional support.”

At that point, James did not know it is illegal to deny students enrollment in a public school based on their special education status. But she soon found out. The Education Law Center of Philadelphia has since taken up her cause, sending an open complaint letter to the school’s lawyer.

Franklin Towne CEO Joseph Venditti did not respond to requests for comment. In an email, the school’s longtime lawyer, James Rocco III, denied the allegations of discrimination.

“Franklin Towne denies all of the allegations set forth in a letter from the Education Law Center but cannot comment further based upon threatened litigation,” Rocco wrote. “I am also in the process of discussing this matter with the attorney at the Education Law Center.”

Kristina Moon, the staff attorney with the Education Law Center (ELC) who helped James write the open letter, said she had not heard from the school or its lawyer except a generic communication in which Rocco informed her that the school’s CEO was out of town.

“We’re eager to discuss this with the school, but we haven’t yet been given any opportunity to discuss the substance of this,” Moon stated in an email.

According to a recent analysis by the ELC, Philadelphia’s charter schools serve “disproportionately fewer of Pennsylvania’s vulnerable students than traditional public schools.” And those gaps are especially wide between special education students with inexpensive disabilities, who are common in Philadelphia charters, and those with expensive disabilities, who are relatively rare.

“Of course, not all charter schools violate the law, but this case fits a citywide pattern that students identified with emotional disturbance — and other more complex disabilities — are consistently underrepresented in charter schools,” Moon said, “even though charters are required to serve all students regardless of any particular special needs.”

The motivation for this pattern is written into the state’s charter school law. School districts in Pennsylvania are required to pay charter schools for each student living within the district who enrolls in a charter school. There is a per-pupil payment for regular education students and a much higher payment for special education students.

The per-pupil payment for each special education student is based on the average cost of educating a student with a disability. But the cost of educating special education students varies dramatically depending on their disability. So a charter school brings in thousands of extra dollars for every student enrolled with a disability that costs less than average, but it also has to spend thousands of extra dollars to educate a student with a disability that costs more than average.

“The charter sector, by and large, does not educate students with disabilities who require higher-cost aides and services — e.g., students with intellectual disabilities, serious emotional disturbance and multiple disabilities,” the Education Law Center’s analysis reads. “Instead, the charter sector serves students with disabilities who require lower-cost aides and services, such as speech and language impairment and specific learning disabilities.”

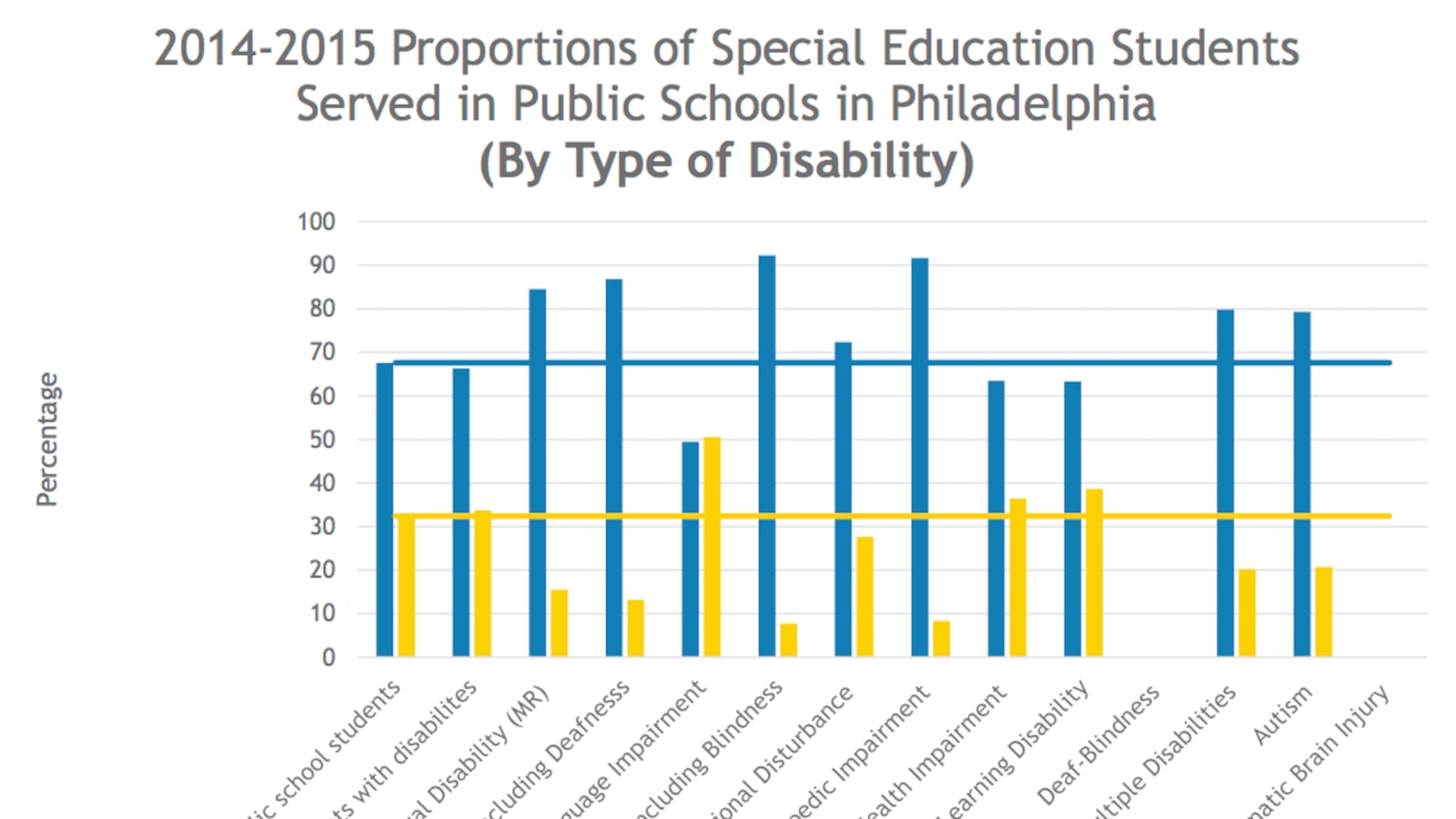

In Philadelphia, charters serve more than 32 percent of all public school students classified as special education, so presumably, they would serve roughly 32 percent of students in each disability category. But that’s not the case.

Philadelphia’s charters serve more than 50 percent of all students with speech or language impairment — some of the least-expensive disabilities — while serving only 15 percent of those with intellectual disabilities — some of the most expensive.

The most expensive students to educate are those with multiple disabilities. District schools enroll roughly four times more students with multiple disabilities than charter schools.

‘A funding windfall’

“Until funding with respect to students with disabilities in the charter sector is equitable, Pennsylvania’s schools will remain and continue to become more segregated by disability and race,” the Education Law Center’s analysis reads. “There is simply no fiscal motivation for charter schools to reform these policies, as maintaining such practices create a funding windfall for charter schools who receive surplus special education funding — and benefit from better performance.”

This pattern is seen beyond Philadelphia as well. In the 2012-13 school year, Pennsylvania’s charter schools received a total of $350 million in special education revenue, but spent only $156 million on special education, according to research by the Pennsylvania Association of School Business Officials. That’s a difference of $194 million.

“The additional dollars that they receive can be used to support the school in any way,” Moon said. “That money is not tracked and does not go to the individual students.”

In 2014, when a state commission was working on a new special education funding formula, charter proponents pushed back against the idea of replacing the flat payment for all special education students with payments that varied depending on the expenses associated with each student’s disability.

“Politicians I’ve talked to just don’t understand what this will do to charter schools,” John Swoyer, CEO of MaST Community Charter in Northeast Philadelphia, told the Harrisburg news service Capitolwire. “There are schools that are on that list that, within six months, the formula would destroy their program.”

The Notebook calculated that Philadelphia’s charters accounted for $100 million — or about half — of the $194 million in special education funding that wasn’t spent on special education. Pennsylvania’s charters spend an average of 45 percent of the special education money they receive on their special education students. And that’s legal under the current charter school law, unless they get caught weeding out certain students based on their particular disability, which would be discrimination.

“It might mean nothing to them, but it means everything to me because my granddaughter was very hurt,” James said. “She told friends at school she was leaving, and everyone was wishing her well. All that, only to have her go back with tears in her eyes.”

‘The whole nine yards’

James’ granddaughter was attending KIPP DuBois Collegiate Academy, but when James moved to Northeast Philadelphia for her new job, her granddaughter’s commute to school became unbearable — nearly two hours every morning. So she asked a coworker about schools in the area with low levels of violence and high test scores.

That coworker told her about Franklin Towne. With a new state-of-the-art building, no tolerance for bullying, and high PSSA scores, the school sounded like a dream come true. They applied through the lottery, and when her granddaughter was accepted, she got a call from the school.

Susan McGeehan, the school’s office manager, also in charge of admissions, called to invite the two of them to tour the school and fill out some paperwork.

“I filled out a whole pack of papers, and we toured the school and bought the uniforms, and they were congratulating her — the whole nine yards,” James said. They paid $27 for a uniform and a $25 “activity fee.”

And with that paperwork, James turned in a copy of her granddaughter’s IEP. Within two hours, she received a call from McGeehan.

“McGeehan said, ‘I’m so sorry, Ms. James, but we will not be able to accept her at this time, because the class she needs is full, and there’s no more room,’” James reported that McGeehan told her. “I was hurt. I called her back the next day. She didn’t answer.”

James said that when she called the front desk and told them who she was, “they transferred my call, but it went to voicemail three or four times. I called back and said to the secretary: ‘You tell her it’s not fair for her not to pick up the phone.’ Ever since then, they’ve just put me right to her voicemail. That’s when I emailed her and the CEO.”

‘I had no choice’

This happened in January, but James has still not been refunded her $52 in fees, despite providing copies of her receipts to the school. This is what prompted her to seek out a lawyer.

“Who do they think they are that they can just avoid people and treat us like we’re under the bottom of their feet?” James said. “It’s bad enough that they didn’t want her to be there, and now they turn around and act like they don’t hear me asking for my money back.”

McGeehan eventually responded via email, telling James that they were not accepting her granddaughter because of James “agreeing” not to enroll her when they spoke over the phone. James said she was not even offered a choice and did not agree to anything.

“I didn’t say I would send her back to KIPP because I agreed; I said it because I had no choice,” James said. “She told me my granddaughter can’t come here. I’m not a fool. That’s exactly what she said.”

“The charter school office is aware of the situation, has worked with the family to try to resolve it, and is trying to work with the school to ensure that all its policies and practices are compliant with what we expect,” said Lee Whack, spokesman for the District.

Whack clarified that, for example, the charter school office does not allow schools to charge fees as a requirement for enrollment. However, Franklin Towne’s fee was labeled an “activity fee,” which Whack said is allowed as long as the fee is optional.

A long history

Franklin Towne Charter High School has a long history of special-education-related violations, according to annual evaluations by the District’s Charter Schools Office.

Most relevant is that for the last three years, the school has consistently violated the “Child Find Notice” portion of the federal Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which mandates that schools identify all students with disabilities, provide for their needs, and inform parents of their rights under the act.

Franklin Towne neither provided for James’ granddaughter’s disability, nor informed her grandmother that she had the right to have those needs provided for.

“Parents need to be made aware of their rights to special education services,” said Moon, adding that the Education Law Center frequently meets with parents who don’t know their rights have been violated because they never knew their rights in the first place.

“All public schools, including charter schools, have the legal obligation to enroll all students and provide services regardless of their needs. … It is the school’s responsibility to inform parents,” Moon said.

As recently as 2016, Franklin Towne was criticized by the Charter Schools Office for requiring accepted students to submit copies of their Individual Education Programs before enrolling them, although this complaint was not made in its most recent evaluation. Requiring these IEPs before enrollment is a violation of state law.

But James’ experience indicates that the practice is still going on.

Manifestation determination

The Charter Schools Office has reported that Franklin Towne has also consistently violated another part of IDEA: manifestation determination. Manifestation determination applies when a school wants to use exclusionary punishment, such as expulsion or long suspensions, on a student with a disability. This provision mandates that the school call the student’s parents to arrange a meeting with special education staff, in which they determine whether the behavior the student is being punished for was the result of a disability.

If the misbehavior was the result of a disability, it is illegal to remove the student from the classroom, and instead, the special education staff must work to provide further support for the student’s needs.

“A school cannot punish a student with a disability for behavior related to their disability,” Moon said. “Manifestation determination is a meeting, an opportunity to assess whether the behavior at issue is related to the disability, so that you don’t discipline a student for acting in a way they can’t control.”

But Franklin Towne has not been doing this, according to the Charter Schools Office.

“The school’s code of conduct does not fully articulate all the conditions in which a manifestation determination meeting must occur, nor does it reference the inclusion of parents,” the Charter Schools Office found.

Secret waitlist

During the phone call in which her granddaughter’s acceptance was rescinded, James said she was told that her granddaughter could be put on the waitlist. But in its most recent evaluation, the Charter Schools Office found that the school does not make that waitlist public, which Moon called a “concern about transparency,” or the lack of it, that creates the potential for manipulation.

“I can imagine a scenario in which someone at the top [of the waitlist] is told she has a spot at the school, but when they find out this child has a disability that the school is not interested in serving, they can remove her and move on to the next person on the list,” Moon said.

In other words, if the list is secret, no one can tell whether the school is actually following it.

“When a charter denies access to their school, those charter schools should be held accountable,” Moon said. “We believe it’s the role of the new school board to hold all schools accountable for appropriately serving our students. So we encourage the new school board to consider not only management and academics when considering a charter, but how they treat all students.”