This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

It’s budget season in the School District of Philadelphia, and the District’s proposed $3.4 billion budget for 2019-20 includes needed investments in special education to fund new positions for psychologists, emotional support teachers, and autistic support personnel. It also includes increased support for special education training, academic advising, and coaching. But the state’s special education funding line item is not the source of support for these new investments.

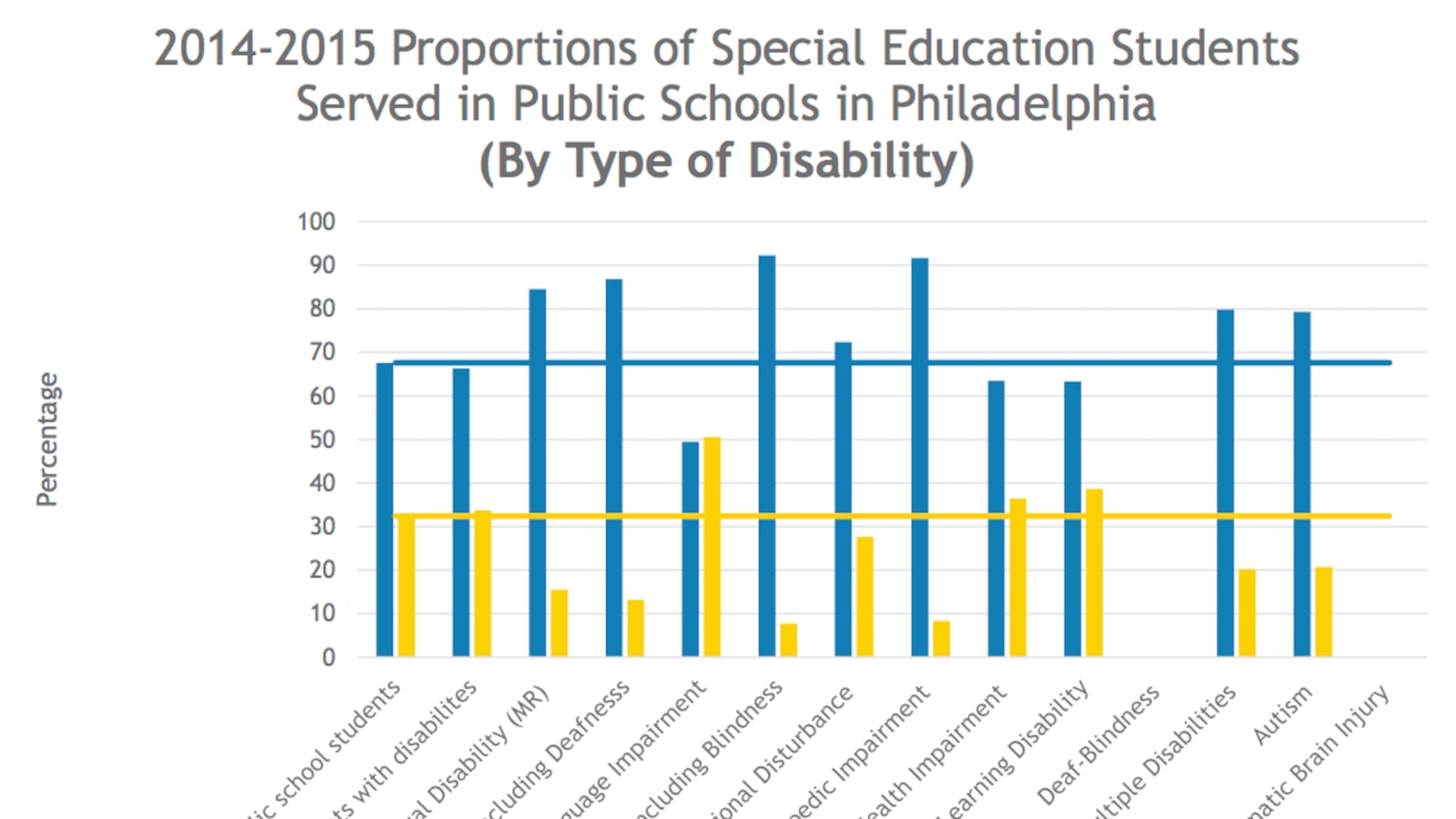

In Philadelphia, as in most Pennsylvania school districts, state special education revenue now accounts for an alarmingly low percentage of overall funding for students with disabilities. Of the $566 million the District spent on special education services in 2017-18, only 25% was supported by funds from the state special education line item. The remaining 75% was cobbled together from a variety of sources, including local taxpayer funding and Medicaid ACCESS, which provides partial reimbursement of District costs for medically related services to students with disabilities.

State special education funding once accounted for a far larger percentage of the District’s special education budget. In 2008-09, the percentage of funding coming through the state’s special education line item was significantly higher, at 42%.

A 2018 report from the Education Law Center (ELC) exposed how dramatically the state’s contribution to special education services has declined as a percentage of overall special education spending. From 2008-09 to 2016-17, the state went from providing over one-third of special education funding to less than a quarter statewide. During that time, as the costs of special education grew, local districts designated close to $20 in additional funds to special education for every additional dollar contributed by the state. The growing reliance on local wealth to fund special education exacerbates inequality between districts.

Funding shortfalls limit student access to assistive technology and other supports and services that can help students with certain disabilities learn more effectively. In a more affluent district, like Lower Merion, per pupil special education spending is as much as double Philadelphia’s rate, for example.

The current level of state special education funding is woefully inadequate to meet the needs of students with disabilities in the District. And ELC believes that many District students who are eligible for special education services have yet to be identified in Philadelphia.

ELC and other advocates argue that addressing the problems of funding for students with disabilities requires increased investments in the state special education line item. But this must be part of larger structural fixes to Pennsylvania’s entire school funding system. Basic education funding–which supports salaries, instructional materials, and other general education costs for all Pennsylvania public school students – suffers from the same funding flaws as special education, including persistent state underfunding, low state share, and overreliance on local district wealth to support students.

Also problematic is the system for special education funding to charter schools, which does not reflect what the General Assembly recommended as the most equitable way to fund education for students with disabilities. In 2013, the legislature adopted a “tiered” special education funding formula that distributes state special education dollars to districts based not only on the number of eligible students but on the actual cost of providing each student the needed level of services. However, this tiered formula currently does not apply to charters.

Charters receive a flat amount for each student that is based on the sending school district’s overall average per-pupil spending on special education services. In some cases, like in Philadelphia, this per pupil payment can be three times the amount for regular education students. As a result, charter special education funding bears no relation to the actual cost of services that charters are providing to students who have varying disabilities. And there is no requirement that charters spend the money they receive for students with disabilities on students with disabilities.

This system creates perverse incentives for both districts and charters. Charters can benefit from underserving students whose disabilities require higher cost educational supports. Districts can hang on to more dollars if they artificially limit spending on special education services in order to keep their per-pupil average low and minimize how much they will ultimately need to pay to charter schools.

The General Assembly must act to resolve these structural funding issues. But City Council is not powerless in addressing Philadelphia’s underfunding. Philadelphia needs every dollar of the proposed increases of $87.3 million for basic education and $9.8 million for special education in the governor’s proposed budget – so the state legislature should quickly adopt it. And City Council should approve the full amount of Mayor Kenney’s request for the District, which represents an increase of $33 million in payments from the city’s general fund, in addition to what is generated through the regular city taxes earmarked for schools.

While these amounts are needed, they are nowhere near enough to ensure that Philadelphia students have the resources to succeed. The state must make significant additional education investments. But it should also enact legislative reforms that accelerate funding to the neediest districts and address the flaws in special education funding to charter schools.

Reynelle Brown Staley is policy director at the Education Law Center.