This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

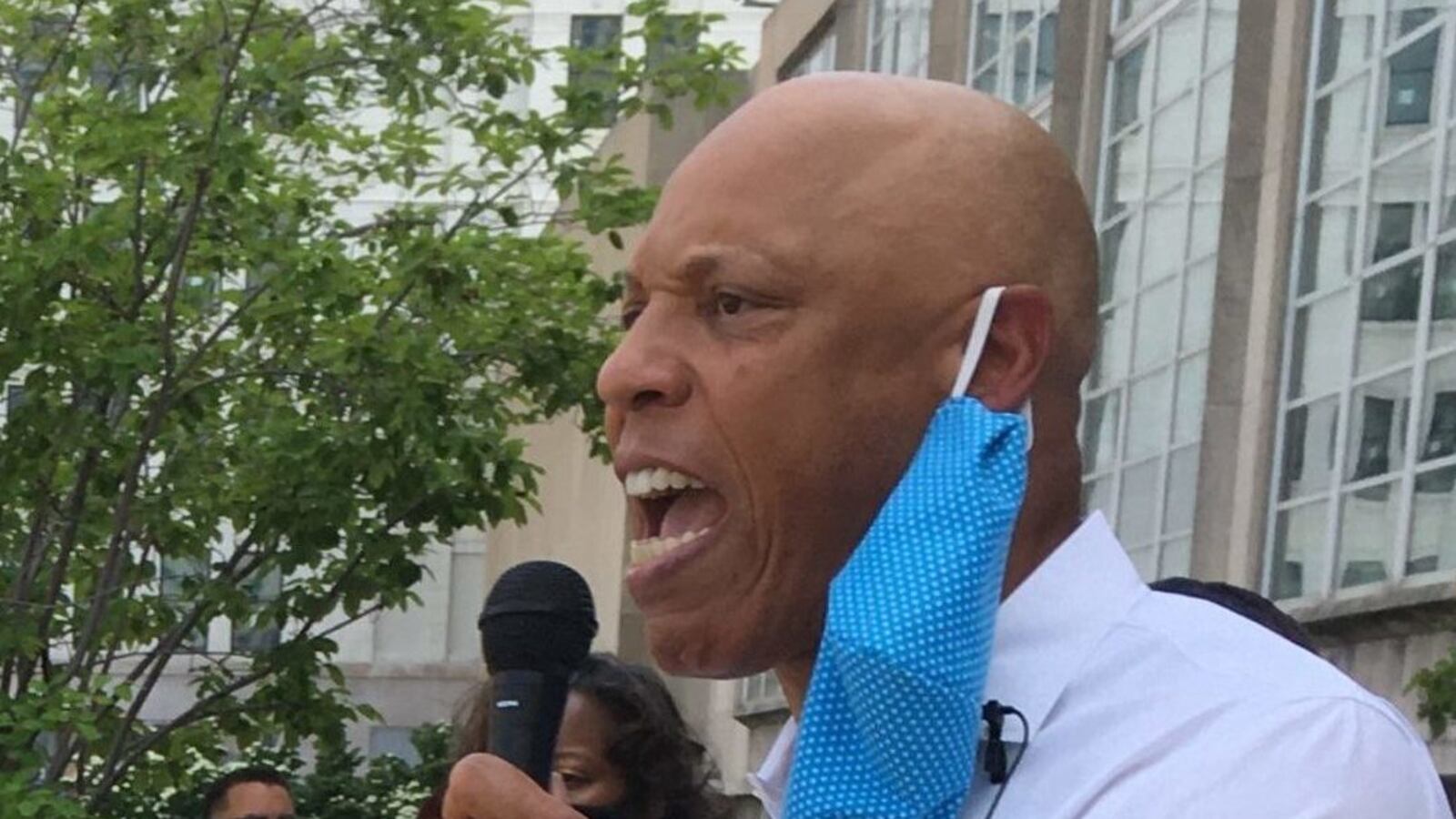

Superintendent William Hite said Thursday that the District is embarking on a major effort to combat racial inequities that exist within it. He declared that “it is our intention to ensure that all our school communities are inclusive and have inclusive cultures.”

Hite and other school officials who are heading up the effort said that the time is right for such a self-examination.

“We are in transformational times as a country and seeing a nationwide conversation on race,” said Estelle Acquah, the special projects director in the District’s leadership development office who is helping to organize the project.

The District is putting together an “equity coalition,” beginning with staff but with intentions to eventually include students, parents, and community members, who will join subcommittees that will spend a year meeting and making recommendations for policy changes.

More than policy, though, the District wants teachers and others who work with students to go deep into their own attitudes and behaviors.

“We’re focused on policy changes, but also on how we address beliefs about our students and their potential, and what they can do,” said Acquah. “We understand that there are always activists on the ground, on the student level, our teachers, our leaders, who have been … passionately calling attention to issues of racial inequity for decades. And what we’re trying to do right now is really give organizational and systemic power to their voices.”

Acquah and Sabriya Jubilee, executive director of school improvement, are organizing the effort.

“The equity coalition is really about providing the organizational leadership and structure needed to design a more equitable district,” said Jubilee. One of the first things it will do is “identify and understand our district’s current demographics through a deep analysis of data and looking at historical trends with a focus on equity,” leading to an “equity audit and subsequent action plan that will highlight our short- and long-term commitments.”

The District sent a statement to staff on Thursday inviting participation in the coalition, saying the effort “is not a sprint, it’s a marathon” and outlining areas of focus. Besides the data analysis, those areas include reframing mission, refining policies “through an equity lens,” promoting cultural awareness, embedding equity training for all staff, and collaborating locally and nationally around equity issues.

“Nothing is off the table,” said Acquah.

By the end of August, there will be more information about the subcommittees and an invitation for parents, students, and community members to participate in them, officials said.

The initiative comes as students, faculty, and alumni of two of the District’s most selective high schools, Masterman and Central, have been highlighting on social media and elsewhere discrimination and microaggressions against Black students. The percentages of Black students in both schools are far below the percentage of Black students in the District as a whole.

Central students called for changes in the school’s heavily test-based admissions policy and more active recruitment of Black students from schools and neighborhoods that rarely send students there. They also want the schools to hire equity officers, review discipline policies, and overhaul curriculum to better reflect the Black experience and contributions.

The president of Central, Timothy McKenna, said in response that he would act on the students’ concerns, hiring a new climate manager and equity coordinator, and opening a frank dialogue about racism, “beginning with implicit bias training for all administrative and faculty members.”

“The goal is for us to collaboratively improve student life for our African American students,” he said in a statement. “I take ownership and recognize changes need to be made.”

The District’s heavily test-based admissions policy for its most desirable magnet schools has come under scrutiny before, only for the effort to be abandoned when parents of students who benefited the most raised an outcry.

“I think the collective will is different now,” Hite said, citing the recent demonstrations, “including lots of young people and people of all races who are talking about just fundamental fairness” and who are ready to acknowledge that “some of these systems that have advantaged some over others based on race and class, are just inequitable, and we can no longer tolerate those in cities like Philadelphia.”

“If we’re going to have antiracist policies, then those are some that we’re going to have to look at and take on, no matter how hard the conversations are,” he said. “We’re just going to have to do that.”

He also noted, as the Central students and faculty did, that the District, at least for next year, has no choice: Administration of the state standardized test, the PSSA, was cancelled due to the pandemic.

Curricular overhaul

Hite said that a curricular overhaul is already underway in social studies and that similar undertakings would occur for English, math, and science.

“We are rewriting most of the curriculum,” he said, so students can better understand different cultures and learn about Black and multicultural history “in a way it was not related before.”

In 2005, Philadelphia became the first big city to mandate an African American history course as a graduation requirement, but this effort, Hite said, will go far beyond that to encompass curriculum in all areas from kindergarten through 12th grade.

The issues go beyond curriculum to staffing. Although all schools are allocated teachers and resources based on the same formula, there is a perception that schools in the poorest areas are shortchanged. Schools like Central and Masterman with more affluent student bodies can draw on parental and community resources in a way that those in low-income areas cannot. Those in the city’s poorest neighborhoods are often in the oldest buildings in the poorest condition. These schools are also the hardest to staff, meaning that they are most likely to have inexperienced teachers or rely heavily on substitutes.

Most of the students in the District are Black and Latinx. Most of the teachers are white — a reality that is true across the country. This needs more honest unpacking, Acquah said.

“That’s absolutely not a condemnation of who can and cannot teach our kids, but really we’re called right now to an invitation to try to bridge cultural divides that we might be seeing in our schools,” she said.

Jubilee said that these conversations will be difficult, but this initiative “is something we hope every facet of the educational community will come together and be part of.” She expects most of the work to take place during the upcoming school year, with recommendations and an action plan ready by next summer, including a “phased strategic plan” for one year, three years, and five years.

But she added that she recognizes that the work will never be completed.

Hite is hoping for a larger conversation that looks honestly at the regional, statewide, and national inequities in education. Philadelphia’s student body is mostly low-income, and Black and Latinx, while it is surrounded by districts that are, with some exceptions, mostly white and relatively affluent.

“The issues of inequity and equity occur in a larger context,” Jubilee said. “There’s no denying there may be a larger impact, and we would welcome that. We are having conversations about what we can engage with on that, and when we can, we will.”

But the immediate focus, she said, “is on our community members, parents and students and teachers, what are their lived experiences. Their voices are most important.”

The Racial Justice Organizing Committee and the Melanated Educators Collective, with other teacher and student activist groups, are planning a “march for Black lives” from City Hall to the District’s headquarters at 11 a.m. on Sunday.