Uncertainty and change have been the dominant features of Salma Gomez’s school years. A 17-year-old junior at Adams City High School, she saw “great teachers” repeatedly leave and get replaced by teachers who were just starting out.

In 2017, she was among several hundred students who walked out of school to demand a greater voice in the future of the struggling school. But nothing improved, leaving students disillusioned. Then this fall, she wondered if Colorado education officials would close Adams City High and force her to go elsewhere even as she was working toward early graduation.

“It’s been like this for years,” Gomez said. “Our trust has been broken.”

That broken trust can be traced back to a complex mix of factors, some of which plague many struggling districts and some which are specific to the Adams 14 district, based in a working-class suburb north of Denver. Among them: constant turnover in district leadership, an exodus of students and teachers, and a constantly shifting approach to educating English learners. Also contributing were divisions between longtime residents and newer arrivals, a mistrust of outsiders, and demographic changes that concentrated poverty within district boundaries.

Now, after failing to improve test scores for eight years, the 7,500-student district faces Colorado’s ultimate consequence of failure: Losing much of its authority.

It’s one of just two school districts in the state that has underperformed for this long.

Late last year, the State Board of Education ordered Adams 14 to hire an external manager empowered to oversee, for at least four years, instruction, teacher evaluation, and other operations. The district retained the ultimate authority to hire and fire employees.

This week, Adams 14 officials start the process of choosing that manager, ushering in more uncertainty, and a measure of hope, for a community long let down by its school system.

That external manager — which could be a public school district or a private consulting firm — will almost certainly face many of the same challenges that led Adams 14 to this point.

Superintendent Javier Abrego and Connie Quintana, the school board president, declined to comment for this story. But interviews with longtime residents, elected officials, advocates, and others portray a district plagued by obstacles — including some of its own making.

‘The community has changed’

The 7,500-student Adams 14 district covers most of Commerce City, a Denver suburb that has traditionally served as an agricultural and industrial hub.

The district includes the historic parts of Commerce City, such as the former town of Derby established around a railroad station in the 1880s and the Rose Hill neighborhood. Those parts of the city are home to many low-income families.

New development on Commerce City’s eastern edge has doubled the city’s population since 2000, but those growth patterns only served to concentrate poverty in Adams 14. Most newly built, higher-priced homes lie within the neighboring 27J Schools, a Brighton-based district.

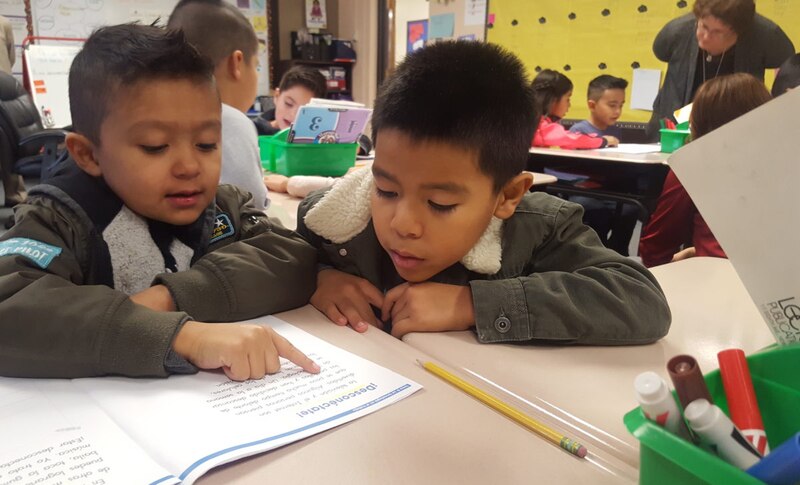

Adams 14 has the state’s highest concentration of English language learners. About half of its students are learning English as a second language — up from 17 percent in 2000. Neighboring districts don’t come close to those rates, and their populations didn’t change in the same ways.

In 27J Schools, for instance, the percentage of English learners has declined.

In the 1970s and 80s, Spanish-speaking immigrant families started arriving in Commerce City. The fault lines between new arrivals and longer-term white and Hispanic residents continue to shape the district to this day.

“You have many people on the board who have spent a lot of time in our community, who grew up in the community, who went to the same schools, but who have trouble realizing that the community has changed and that the schools are different,” said Dominick Moreno, the newest Adams 14 board member, and a 2003 graduate of Adams City High School. “I’ll be honest, even I am not completely connected to the parents and students in Adams 14.”

Officials in Adams 14, like their counterparts elsewhere, say that state funding falls far short of providing them enough money to help the high number of at-risk students the district serves. And voters consistently have rejected pleas to increase local taxes to increase funding or to fix or replace aging schools.

Most students in Adams 14 face multiple challenges, but the state doesn’t provide more money for each identified need. A student who is learning English, for example, gets the same amount of additional funding whether he or she lives in poverty or comes from a middle-class home.

In 2000, 56 percent of the district’s students qualified for free or reduced price lunch, a common measure of poverty. By 2017-18, the figure had risen to 86 percent — the fifth highest rate in the state.

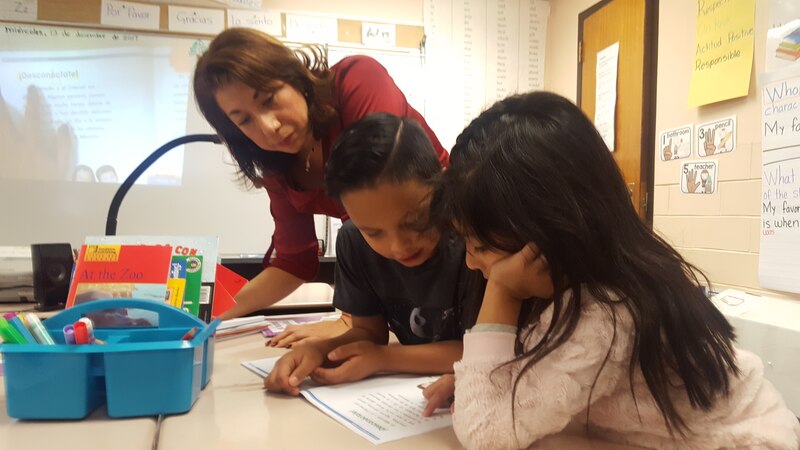

As the district’s Hispanic student body also grew, activists started pushing in the 1980s to train bilingual teachers and teacher’s aides. But holding onto those teachers proved challenging.

Around 1996, “the district really recognized the amount of students coming in from monolingual families,” said Larry Quintana, a long-time community activist and former school board member. “Adams 14 was a leader in trying to put together a program to educate these kids.”

In 2000, Adams 14 even began recruiting teachers from Mexico, securing for them three-year visas to teach in two languages.

But the district found itself on the losing end of a severe competition. As soon as teachers were trained as bilingual educators, other districts would woo them away with higher pay.

“We would go back to ground zero,” Quintana said.

Then a new federal focus on accountability and state testing changed the way many educators thought about teaching bilingual students. From 2001 it became more important to ensure students could test well in English, as soon as possible. It resulted in a retreat from bilingual education.

“That was a big shock to all the educational systems, but in particular Adams 14,” Quintana said.

Quintana said that turnover in the district has always been a problem, but that it got worse as the district transitioned from a country-town feel to an urban-type community where many administrators migrated to bigger districts to advance their careers.

One superintendent after another

The school board worsened turnover by hiring and firing superintendents. Not counting interim leaders, the district has been through four superintendents in 10 years — with each of the previous three removed unexpectedly — and work in progress often vanished with them. With those changes also came radically different approaches to instruction for English learners and attitudes toward them, causing problems that continue to this day.

In 2008, after 10 years as a superintendent who supported bilingual education initiatives, John Lange was suddenly removed. Board members pointed to financial problems, including the conviction of an employee for embezzlement and a growing budget deficit, which Lange disputed at the time.

The next superintendent, Sue Chandler, began an English-only practice that did away with foreign teachers, bilingual education, and Spanish outreach to families.

Around 2010, the federal education department opened two investigations into the mistreatment of Hispanic families, students, and staff. Findings issued in 2014 indicated the district had violated their civil rights.

In one example cited in the findings, an elementary school principal yelled at kindergarten and other students, ordering them to speak in English when asking for help and food in the lunchroom — even though the kindergartners were monolingual Spanish speakers.

“It was reported to us that when Spanish-speaking staff tried to intervene and assist these young students in Spanish, the principal stopped them,” the report read.

The principal denied the incident, but did tell federal investigators that one of the goals of the new program was to “eradicate” the native language.

The federal government ordered measures to correct the violations, including training, revised harassment policies, and a system to track complaints.

By the time the findings were published, a new school board had removed Chandler and brought in another superintendent, Pat Sanchez, a Hispanic man tasked with cleaning up the district’s discriminatory image.

In 2016, Sanchez faced a community call for his removal and allegations of harassment. After he accepted a job elsewhere, the board voted to remove him mid-contract in May of that year.

The board replaced him later that year with Abrego, an Arizona educator who promised to improve the district in two years.

Last November, the federal Office for Civil Rights told the district — and the state — that Adams 14 hasn’t followed through with the 2014 agreement and is still violating the rights of students.

“With each new administration in the district, there is a pattern of a systematic departure of individuals who possess appropriate expertise, knowledge, and understanding of all aspects of the alternative language programming for the district … as well as individuals tasked with implementing the district’s steps to address and remedy the hostile environment,” the letter states. “As a result, the district effectively starts over with its compliance efforts with each new administration.”

The State Department of Education, in laying out the plan to improve Adams 14, required that the external manger abide by the federal order.

Moreover, the district has seen a spike in the exodus of top leaders in the last year. Abrego has downplayed the departures, saying it was all part of his reorganization plan.

Abrego had made other moves that have proven controversial. He halted expansion of a biliteracy plan created by former superintendent Sanchez. The plan called for rolling out the Spanish-English framework to classes one grade level at a time, and adding schools as more teachers became trained to run those classrooms. Abrego ended the partnership with the university that provided the teacher training and classroom resources. He questioned academic progress based on the program’s first class, and cited a shortage of teachers.

Turnover in the district has not been limited to the top. Adams 14 also has seen significant turnover among board members, administrators, and even teachers.

Adams 14 has one of the highest rates of teacher turnover in the metro area. In 2017-18, almost 45 percent of teachers were in their first or second year with the district.

Trish Ramsey, one longtime middle school teacher and union leader, said that her students notice.

To try to ease their fears, she often reassures them that she isn’t leaving. But one day when she was explaining she would be gone for a couple days while attending a state hearing, her students panicked. “You said you wouldn’t leave us,” she recalls they told her.

Older students attending community meetings last month asked Adams City High School Principal Gabriella Maldonado why they are missing teachers halfway through the year. At the end of December, the district’s website listed 12 job openings at the high school, including for four teachers and a learning specialist.

The district had managed to fill most of those positions by mid-January, with students once again seeing new faces in their classrooms.

Students in the district are also leaving. About 30 percent of the students who live within Adams 14 boundaries attend school elsewhere — including more than 2,300 Hispanic students. Their departure costs the district state revenue.

All the coming and going of district leaders makes many people nervous about an outsider coming in to manage Adams 14 for four years. The constant turnover, switch in directions, and perceived refusal to heed community concerns have taken a toll — and the appointment of an external manager raises the possibility of even more turnover.

‘We start fighting amongst ourselves’

Community members still struggle to trust the district — and even to trust each other. The school board and top administrators remain locked in a contentious relationship with many parents and students.

The fate of the biliteracy program has been just one of many controversies during Abrego’s tenure that pitted the community against the administration: He ended in-person parent-teacher conferences and cut recess at elementary schools, only to reverse course in the face of public outcry. He also opposed efforts by KIPP to open a charter school that some parents wanted as an alternative to district-run schools.

And the community’s divisions include tensions between older white and Hispanic residents and more recent Hispanic immigrants.

Recently, some officials and residents have blamed the district’s problems on parents, particularly newer immigrants, who they believe are not involved in helping fix the schools.

Ramon Del Castillo, a professor of Chicano studies at Metropolitan State University of Denver, points out that this intergenerational conflict is common.

“We start fighting amongst ourselves because we somehow believe we’re better,” Del Castillo said. “It doesn’t allow people to work together.”

While some district leaders have called community turnout of 60 to 70 people at recent meetings impressive, others have been vocal in saying it’s not enough.

Connie Bonnell, one of the co-chairs of the District Accountability Advisory Committee, in December pleaded with the community to reach out to their friends and neighbors to get involved. In a district of more than 7,000 students, she said, filling up the high school auditorium should have been easy.

Timio Archuleta, who resigned from the school board last summer, also took aim at parents at a school board meeting in October.

Despite asking parents to attend meetings, he said, “they don’t get involved. They don’t come. They only want to complain.”

Hearings on the KIPP charter proposal drew many parents and advocates to speak to the board earlier in the year, most in favor of KIPP. Those parents have stepped back, though, with some saying they are scared of retaliation for supporting a charter school opposed by many teachers. The KIPP proposal became one more dividing line.

Some took issue with Archuleta’s comments, including Jorge Garcia, executive director of the Colorado Association for Bilingual Education, who was removed by police from a September board meeting when he criticized the district.

“There is an attitude that we can be as involved as we want; however, the reason we’re not here is because you never listen,” Garcia said.

Garcia, an advocate for bilingual education, became involved in the district about a decade ago, initially to help speak on behalf of Spanish-speaking parents when they complained of discrimination or being pushed away from schools. Many of those parents, he said, have moved on to other districts or have students who have since graduated.

A wariness of outsiders

School district board members David Rolla and Connie Quintana (who is married to Larry Quintana) also make a point of differentiating between those who live in the district and those like Garcia or some teachers who don’t.

Both refused to comment for this story, but comments they’ve made at public meetings suggest a feeling that’s prevalent among many longtime community members: distrust of outsiders.

Over the years, community members have seen many “outsiders” come into the district promising to help, only to leave shortly after, leaving the district in often the same or worse conditions. At the same time, many teachers and district officials have resisted outside guidance. Independent evaluators working with the state identified inconsistent implementation of new programs. In board meetings, members were often caught off guard by information presented by state officials.

The community’s resistance to outside-forced change will make the outside manager’s job tough, but some officials see glimmers of hope.

In an effort to be more responsive to the community, the district has repeatedly extended the timeline for soliciting proposals for an external manager and rewritten the request multiple times. Community members stressed that applicants must demonstrate experience in working with similar communities.

Some officials point to the district’s work with a consultant, Team Tipton, as an example of how it is improving listening and communication with the community. The consultant has run numerous public meetings to talk about the state of the district and conducted a communitywide survey with a surprising result: Parents are mostly optimistic about the district’s future, even as they don’t trust the current administration.

Lisa Medler, the district’s case worker for the Colorado Department of Education, said she has always tried to stay positive about the district’s ability to progress. For years as the district scored low in state ratings, state regulators have provided financial help and other guidance. But she laments that state law has limited how her department could help.

“I feel like we have to work very hard in a high local-control state,” Medler said. “Colorado is pretty unique in that perspective, so that’s definitely been a factor.”

Things are slowly changing, she said. Money that the department gives struggling districts now has fewer restrictions on it, enabling Adams 14 to use it for improvements. The district this year is hoping to tap into it for its external manager.

And Adams 14 officials seem to be more open to seeking help and working with their community.

“We’ve been really encouraged by that direction,” Medler said.

Gomez, the high school junior, said she’s glad to see the appointment of an external manager, something she believes has long been needed. She did well in school, but she attributes her success as much to her own initiative and persistence than to the instruction she received.

Instead of heading to college after graduation, Gomez intends to take a break, in part because of the stress and anxiety caused by all the instability she’s experienced in school.

She plans to spend her time off working to improve the schools for those who are coming behind her.

“We need to be the voice for ourselves,” she said. “This is our future.”