A mayoral commission designed to bring competitive district and charter schools together began to take shape on Monday.

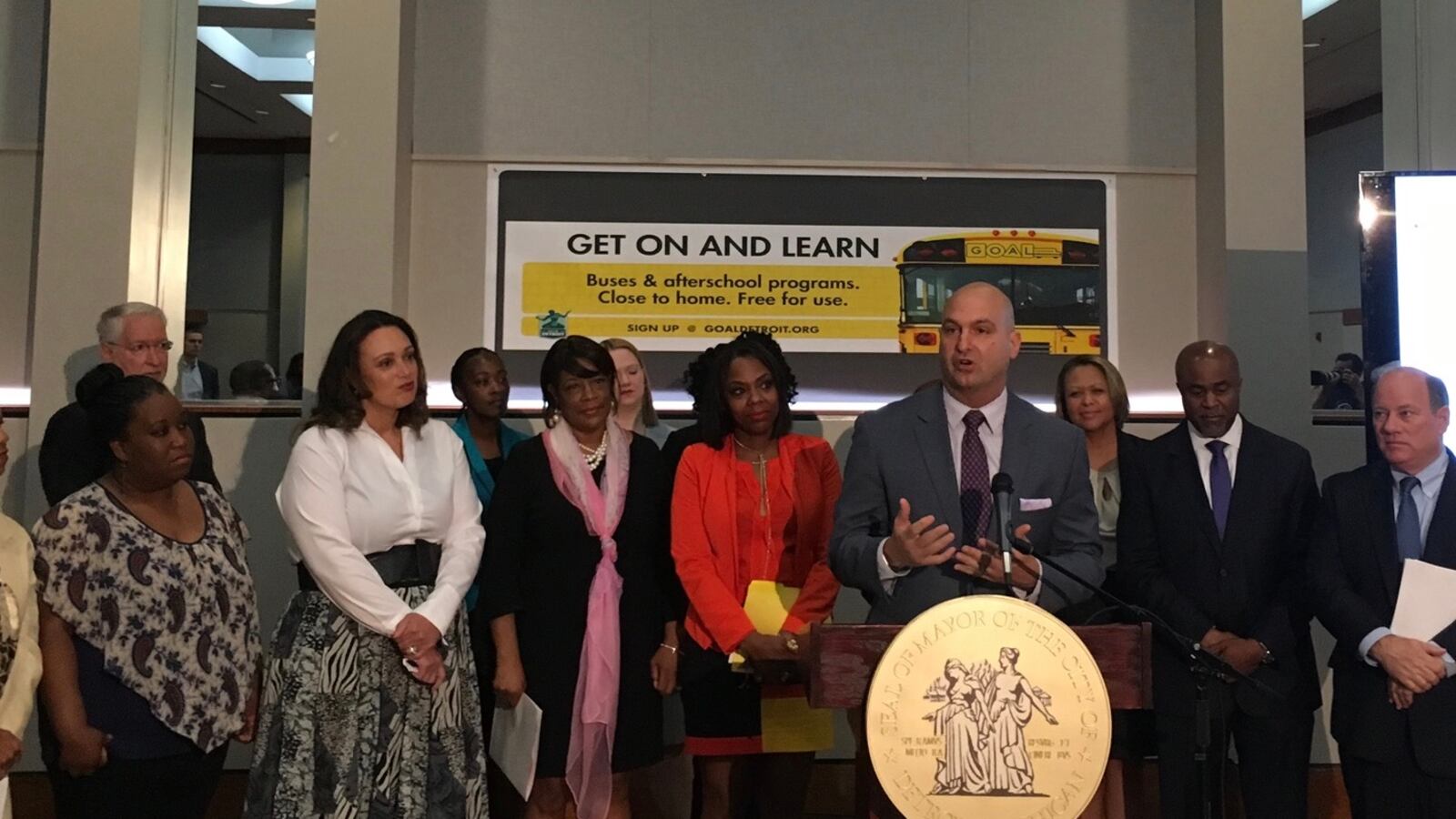

Speaking before television cameras at a recreation center on Detroit’s northwest side, Mayor Mike Duggan named the people who will lead the commission’s signature project — a bus loop that will carry students to charter and district schools this fall, along with after-school programs.

Duggan also confirmed for the first time that the loop will feature a tracking system capable of sending text messages to parents each time their child gets on or off the bus and swipes an identification card. The loop will give as many as 200 children access to after-school programming, including swimming and tutoring, at the Northwest Activities Center.

The mayor’s announcement signaled the opening of enrollment for the program. Parents can visit its website or call 313-224-1222 to enroll.

The appointees to sit on the Community Education Commission are:

- Monique Marks, Franklin Wright Settlements, commission chair

- Nikolai Vitti, superintendent of Detroit Public Schools Community District

- Tonya Allen, head of the Skillman Foundation

- Marsha A. Lewis, a DPSCD teacher

- Ralph Bland, manager of University Yes Academy

- Rachel Ignagni, a teacher and founder of Detroit Achievement Academy

- Nate Walker, of the American Federation of Teachers in Detroit

- Teferi Brent, of Detroit 300 and Goodwill Industries

- Sherita Smith, of Grandmont-Rosedale Community Development

- Vanessa Kessler, of the state Department of Education

- Matthew Simoncini, former head of Lear Corporation

Bland said the loop will benefit students at University Yes, his school, but said more cooperation is needed.

“It’s not charter school students and DPSCD students, it’s Detroit students,” he said. “At the end of the day that’s what it’s all about: Detroit students.”

The commission’s founding document makes clear that the group’s focus could expand. The group may organize an effort to rate Detroit schools, and serve as a clearinghouse for other philanthropic projects in the city’s schools.

The bus loop is intended to fight the tide of students who leave Detroit’s borders to attend school. Almost half of the city’s school-age children attend the main district, with another 30 percent attending charter schools, and the remaining 27 percent — more than 30,000 children — attending a private school or a public school in the suburbs.

But a few extra buses alone won’t be enough to reverse that trend, Vitti said after the press conference.

“There has to be a broader network of transportation lines,” he said. “But most importantly, there has to be an improvement of student performance, and student safety, and quality of programs and instruction.”

While most details were already known, Duggan’s announcement marked the first time the plan was completely unveiled after months-long negotiations that were not without speed bumps.

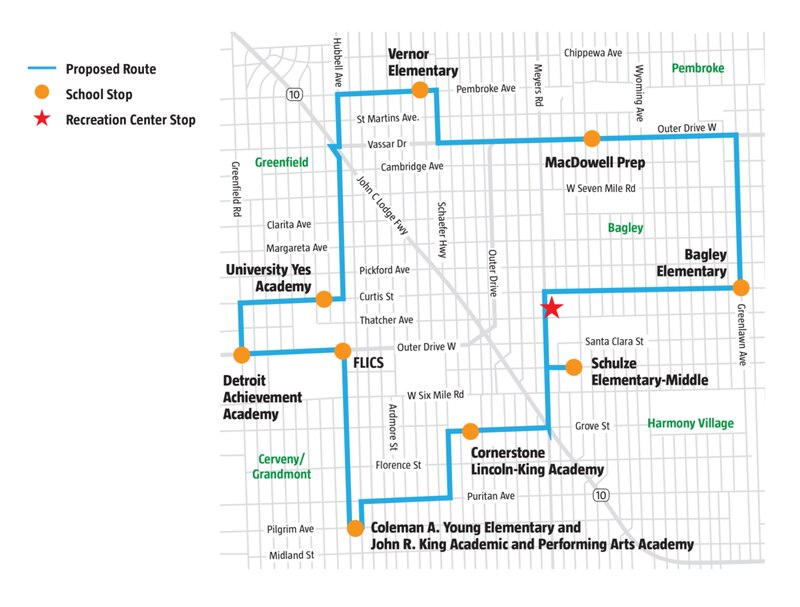

The newly named GOAL Line (GOAL stands for “get out and learn”), will run from 6:30-9:00 a.m. and 2:30-6:30 p.m. on school days. Four buses will transport students between 10 school buildings — four charter and six district schools — covering roughly a five-square-mile area on Detroit’s northwest side.

The program is open to any parents who want to put their children on a bus at one of the participating schools. In the afternoon, the buses will stop at the Northwest Activities Center, where after-school programming will be provided to a maximum of 200 students.

Expected to cost upwards of $1.2 million, the project will be paid for by three parties, and each will contribute about one-third of the expense.

Duggan says the project is expected to continue for five years, and he wants to add more bus lines to other areas of the city before then. Detroit’s main district, however, reduced its commitment to one year amid concerns about the cost of the program. Board members plan to reevaluate the program next spring.