The trove of New York City charter-school data released by the Independent Budget Office this week answered a few questions about how schools replace students who leave, but raised many more.

Between 2008 and 2013, the report showed that a set of elementary schools filled seats that opened up between kindergarten and third grade, and most — though not all — filled seats that opened up in fourth and fifth grades. But which schools were which?

Chalkbeat readers wanted to know, especially since the IBO had ranked individual charter school networks by their schools’ average scores on state tests. “Why aren’t we seeing individual attrition and backfill rates or at least by network, as they did with the ‘performance’ rankings?” one commenter wrote on Monday.

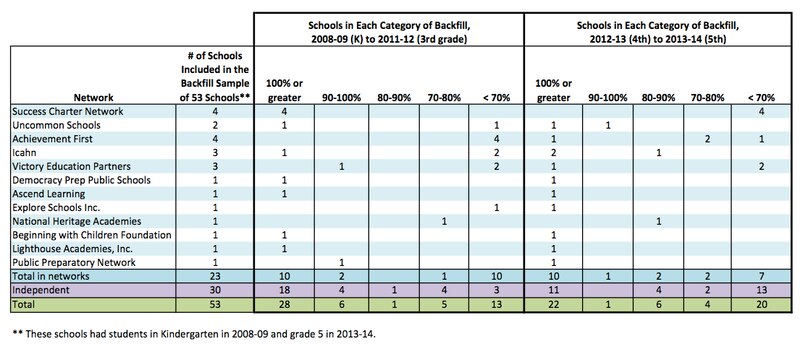

We asked for a more detailed look at the “backfill” data, which the IBO provided and we’ve summarized in the tables above. The additional information sorts the data by charter network.

It is still a very limited slice of information about 53 charter schools with a kindergarten in 2008 and a fifth grade in 2013. (The city had 183 charter schools operating by 2013-14.) Middle and high schools were not included. And some schools have changed their policies in the seven years since this cohort of kindergarteners entered school.

But it is a rigorous look at what those schools did when students left, an issue that has divided charter leaders in the past. Most schools fill those seats with new students, though some restrict backfilling to younger grades. Recently, leaders within the sector and critics, including the city’s teachers union, have said that charter schools that don’t backfill are failing to serve their fair share of needy children, and that the tactic can be used to boost test scores. Some schools say restricting enrollment of older students is necessary for maintaining school culture and advanced academics.

The bigger networks, like Success Academy, have often been criticized for not backfilling, but the IBO’s more detailed data shows a divide among independent charter schools, too.

Nearly half of the independent charter schools filled less than 70 percent of their open seats when when the cohort of students was in fourth and fifth grade. Four Success Academy schools, one Achievement First school, and two schools affiliated with Victory Education Partners fit into that low-backfill category in older grades. (Achievement First spokeswoman Amanda Pinto noted that its schools now backfill their open seats.)

The IBO also looked at whether schools backfilled their seats over the entire six-year span. Half of the schools reached a 100 percent overall backfill rate between kindergarten and fifth grade, including the four Success Academy schools, even though their backfill rates were low in fourth and fifth grade.

Enrollment numbers from the state help explain that conclusion, showing that Success grew its cohort a sizable amount before third grade. Harlem Success Academy 2’s 2008 kindergarten class started with 106 students, grew to 135 students by third grade, then shrank back down to 100 students in fifth grade, for example.

Ann Powell, a spokeswoman for Success Academy, noted that the network typically opens schools with smaller cohorts and expands them as the school grows.

“In 2008, we had only two years’ experience of opening/operating schools,” Powell wrote in an email. “Most likely if you looked at any new organization in its first few years you might see patterns that would be different in later years.”

Ray Domanico, the IBO’s director of education research, cautioned that the more detailed information still should not be used to “make generalizations about the relationships among networks, backfill policies and student achievement.”

“The analysis to study those issues would be complicated,” Domanico said, “and would have to rely on student level analysis.”