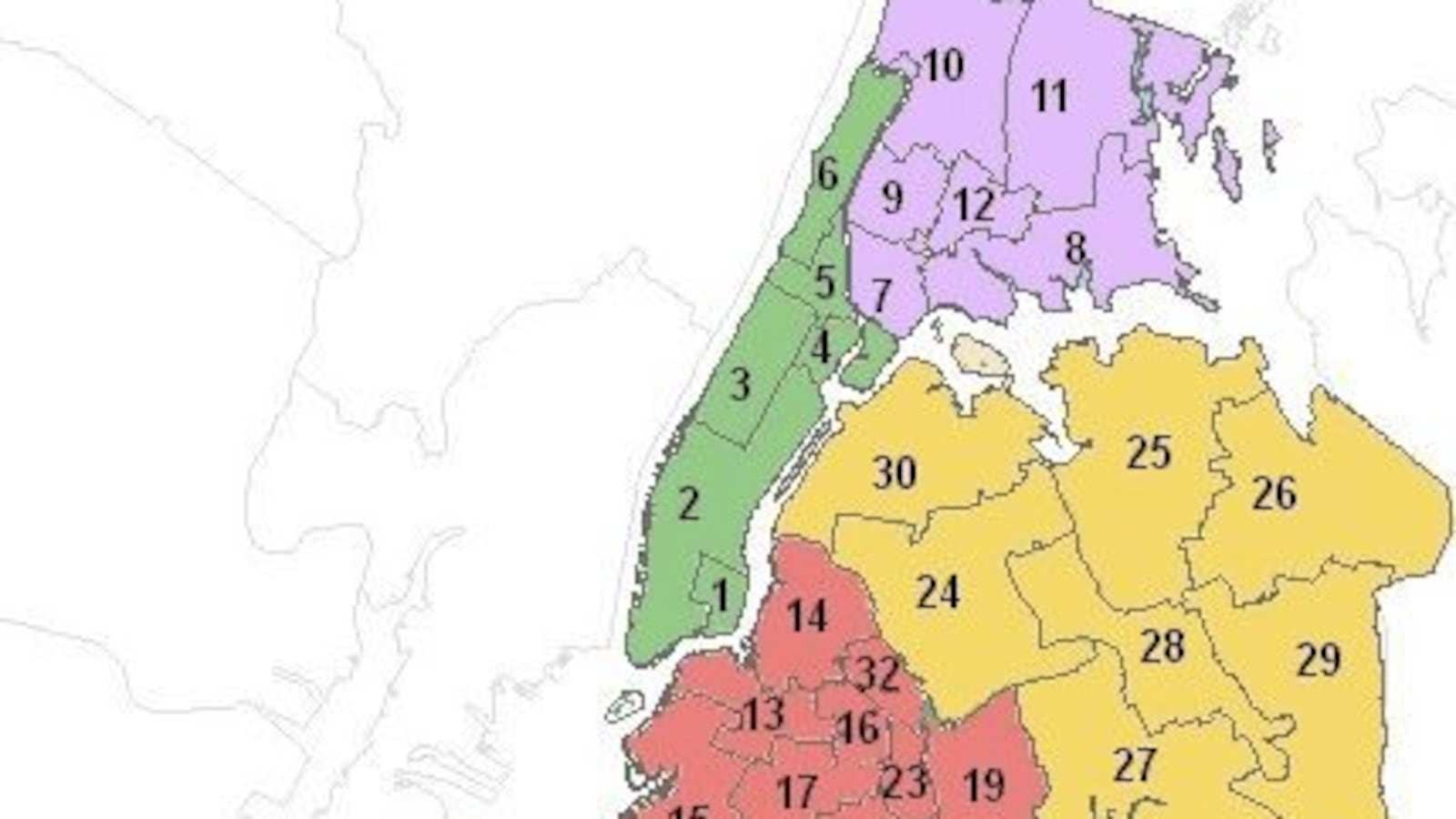

As the school year ramps up, so do plans to integrate New York City classrooms.

School segregation in one of the country’s most diverse cities dominated headlines over the last school year. Across the city, parents, education leaders and elected officials are tackling the problem.

Some plans are small-scale, individual school approaches. The city Department of Education announced in May that any district school could submit plans to change enrollment policies to increase diversity.

Other proposals have the potential for district-wide impact. In many cases, those plans are bubbling up from the districts’ Community Education Councils, but any changes to enrollment policies still require Department of Education approval.

Here’s a quick look back at what has already been accomplished in those districts — and what to expect in the months ahead.

District 1

Stretching back to the 1990s, elementary schools in District 1 on the Lower East Side weighed student diversity in admissions decisions. That changed under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, leaving a pure choice policy in place.

In some Lower East Side schools today, 100 percent of students are low-income; in others, only about 20 percent are. That’s compared to a poverty rate of 69 percent district-wide. But the area includes a rich mix of students: 21 percent Asian, 17 percent black, 42 percent Hispanic and 17 percent white, according to city figures.

Now the district is trying to get back to its roots. With funding from the state’s Socioeconomic Integration Pilot Program grant, or SIPP, community members hope to implement a plan to make elementary schools more reflective of their neighborhood.

Diversity advocates are pushing for a “controlled choice” system that would reintroduce student diversity as a consideration in admissions. Under a proposal presented in March, students would be assigned an “at-risk” score based on family income, disability status and other factors. Families would apply to three to five schools, and a computer algorithm would determine assignments.

In July, a consultant working for the district said the plan had been presented to a top-level official at the city Department of Education. On Tuesday, a DOE spokesman said the consultant is currently using city data to model how the proposal might work. “We look forward to discussing the results of this analysis when complete,” he wrote in a statement.

An update on the general proposal is expected at the CEC’s October 5 meeting.

District 2

In meandering District 2, which covers most of lower Manhattan and the Upper East Side, the integration conversation is just kicking off.

The Community Education Council recently launched a diversity committee to explore inequities in district middle schools, most of which are already unzoned.

District 2 includes a mix of students — 23 percent Asian, 16 percent black, 33 percent Hispanic and 24 percent white, according to city figures. But those demographics are not represented in many of its middle schools, with Asian students clustered at some and white students disproportionately represented at others — and poverty levels ranging from almost 100 percent of students to less than 10 percent at some schools.

“I think everyone on the CEC recognizes that our schools are segregated and we ought to do something about it,” said Shino Tanikawa, chair of the district’s diversity committee.

It’s too early to tell what integration plans might look like in the district. Tanikawa wants to host community forums to get feedback on what changes are needed.

Tanikawa suspects advocates will have to assuage concerns from both parents and principals about the potential impact of mixing high-achieving students with struggling learners — something she plans to present research on. To make sure schools and teachers are equipped to meet the needs of all students, Tanikawa hopes to gradually phase in any changes to school admission policies.

“It will be very difficult but, luckily, research is on our side,” she said. “In the end, this is deeply personal and emotional for each family.”

Tanikawa hopes the community can agree on a proposal, or a set of recommendations for the city Department of Education, by the end of this school year.

District 3

In the Upper West Side’s District 3, a long-fought rezoning battle could change admissions boundaries for 11 schools.

The district’s students are 8 percent Asian, 23 percent black, 34 percent Hispanic and 31 percent white. Half of students live in poverty.

City planners and the Community Education Council say the rezoning could relieve overcrowding while increasing student diversity. But debate around only a few schools with vastly different demographics threatens those goals — and has largely drowned out voices calling for more ambitious, district-wide plans.

Parents have come out in droves to protest a proposal that would shift some students from P.S. 199, a school with stellar test scores and a majority-white student body, to P.S. 191, which serves mostly black and Hispanic students from the surrounding public housing, and has struggled on standardized tests.

Some advocates in District 3 hope to shift the focus from individual schools to a truly district-wide vision for integration. The District 3 Equity in Education Task Force, along with a recently formed group called New York City Public School Parents for Equity and Desegregation, is pushing for controlled choice as an option.

“It’s like they’re addressing the symptoms of this lack of school equity and segregation in the schools, but there’s little effort to think about it more broadly and more constructively,” said Chris Parkman, the parent of a fourth-grader at P.S. 75 and a member of Parents for Equity and Desegregation.

Some CEC members have also called for schools in Harlem, on the northern edge of District 3, to be included in rezoning conversations.

City planners hope to present an official rezoning proposal this month, with a CEC vote expected in November.

District 13

District 13 in Brooklyn, like District 1 in Manhattan, landed a state SIPP grant that local leaders want to use to explore large-scale integration plans. The district — which includes Brooklyn Heights, Vinegar Hill, DUMBO, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Fort Greene and Prospect Heights — is targeting its middle schools.

The students in the area are 19 percent Asian, 48 percent black, 16 percent Hispanic and 14 percent white. Almost 67 percent are poor.

Under the grant process, the district has already opened a bilingual program in M.S. 113 Ronald Edmonds Learning Center in Fort Greene. Community members hope the program will make the under-enrolled school more attractive to the community and to newcomers as the neighborhood gentrifies.

“This is not about telling people where to go. It’s about creating a system where people can make choices that encourage diversity [and] integration,” said David Goldsmith, president of the Community Education Council in District 13 and a member of the SIPP working group. “Because we know that’s what works and what’s good for our kids.”

Goldsmith said the SIPP working group hopes to present its larger integration plans to the community by January, and to get final approval from the city by June.

District 15

In District 15, which includes Park Slope, Carroll Gardens, Red Hook and Sunset Park, a grassroots group of parents is looking for ways to make applying for middle schools easier — and more fair — for all students.

The district’s demographics create an opening for integration: 16 percent of students are Asian, 15 percent black, 38 percent Hispanic and 28 percent white, according to city stats. More than half — 66 percent — are poor.

As Chalkbeat reported in July, District 15 Parents for Middle School Equity has surveyed community members about the difficulties of the application process, and is working to rally supporters to make changes.

The group is also pushing its CEC to organize forums so frank discussions on segregation — and the search for solutions — can begin. So far, Parents for Middle School Equity hasn’t endorsed any particular integration plan over another.

“The conversation needs to start with listening to parents and listening to the educators,” said Miriam Nunberg, cofounder of the group.

Nunberg said the group may use New York City Council participatory budgeting sessions to request money that could be used to explore diversity plans. City Councilman Brad Lander represents much of the area, and has been an outspoken voice on school segregation issues.

“There are a lot of ways it can happen,” Nunberg said. “We believe very strongly that the community is able to come up with a better process.”

This story has been corrected to reflect that District 13’s SIPP working group, not the CEC, hopes to present an integration proposal in January.