Since 2012, Tennessee has used financial incentives to lure some of its most effective teachers to work in struggling schools under an intense turnaround model known as the Innovation Zone.

The strategy appears to have worked. But even as students in iZone schools have shown academic gains, one question has nagged: Did students in schools left behind have to lose in order for students in iZone schools to win?

Researchers examining student achievement in the exited schools are now offering answers. In short, their analysis shows that those students experienced a small negative effect, especially in reading and science. But it wasn’t enough, they concluded, to offset the positive work happening in the iZone.

That’s good news for a state that has invested heavily in school turnaround work through initiatives like the iZone. And it suggests that offering financial incentives to recruit the best teachers to struggling schools is a good strategy to equalize access to high-quality instruction.

The analysis, released Thursday, was conducted by researchers at Vanderbilt University and the University of Kentucky through the Tennessee Education Research Alliance, a partnership between Vanderbilt and the Tennessee Department of Education.

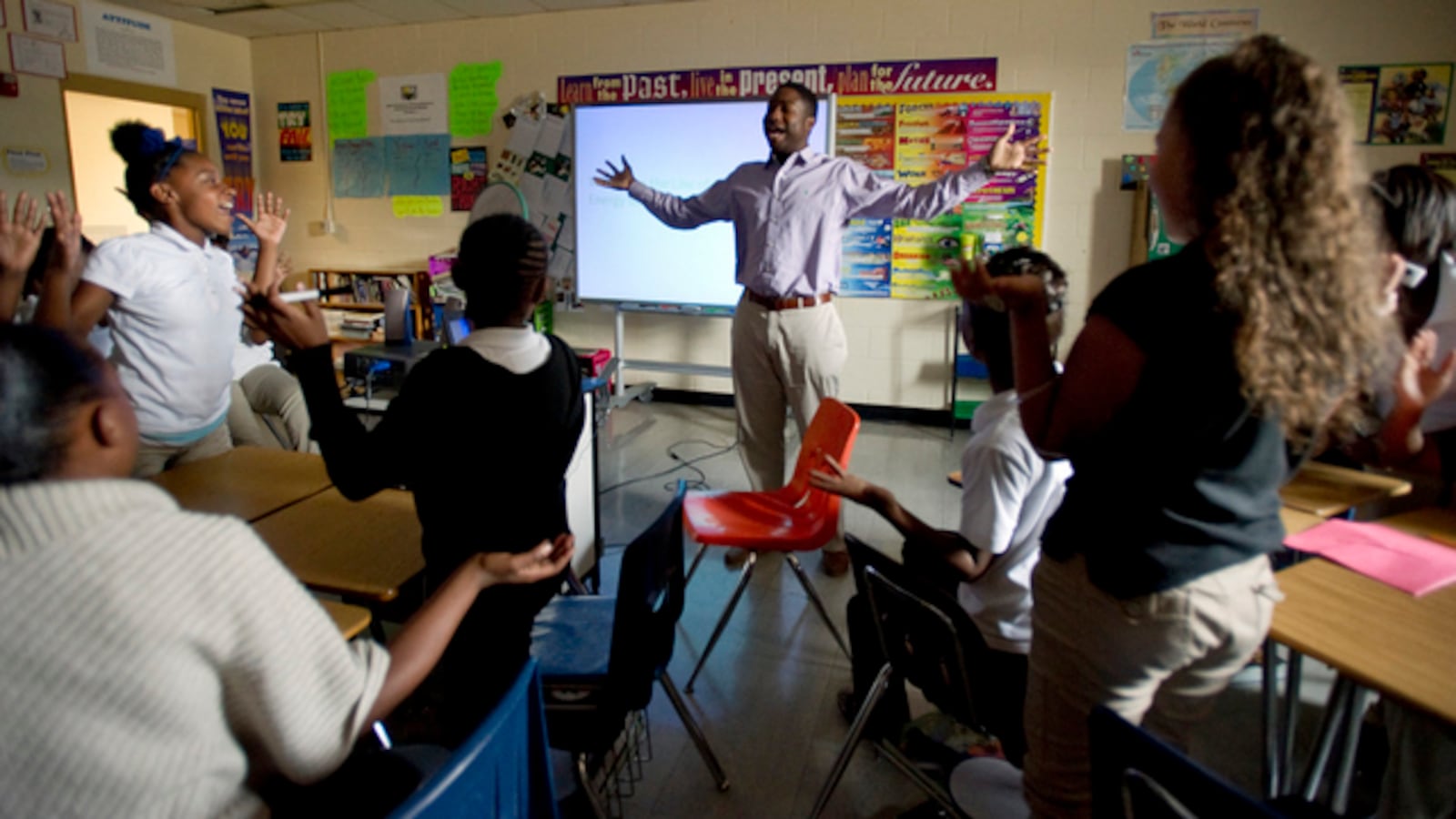

Tennessee’s vaunted iZone serves mostly minority and economically disadvantaged students in chronically struggling schools. To turn them around, the model gives local districts the freedom and funding to add resources, write their own curriculum, and extend the school day. But the recruitment of top principals and teachers is its linchpin, incentivizing the work with hiring bonuses, retention bonuses, and extra pay.

In all, 652 teachers transferred into one of 26 iZone schools in Memphis, Nashville and Chattanooga in the three years ending in the spring of 2015. Most came from within their districts.

Researchers looked at the data of more than a third who previously taught grades and subjects that were tested by the state. They compared gains in grades that lost their teachers to the iZone to other grades in the same school that didn’t lose teachers to the iZone. The loss was small, and researchers concluded that achievement gains in iZone schools more than made up for it.

“It shows that this strategy of providing bonuses and salary increases to recruit highly effective teachers to low-performing schools is still worth pursuing,” said Gary Henry, one of the researchers and a professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt University.

“And based on our research, communities that are worried about losing teachers to the iZone shouldn’t be as worried,” he added. “These are usually higher-performing schools that have many natural advantages in recruiting effective teachers.”

At the heart of the iZone turnaround model is the reality that low-performing schools struggle to compete for the best teachers. When they get extra money, they often seek to reduce class size, then end up hiring novice teachers or those who aren’t trained to teach the assigned subject matter.

“Turnaround work is very difficult,” Henry said, “with extra duties, extra requirements, long days that even sometimes include walking their students home because of potentially unsafe conditions. Without incentives, teachers often gravitate to other schools where they can feel more rewarded and have fewer challenges. But this model levels the playing field. And our study makes it appear that it’s not coming at a large cost to the schools that lose these teachers to the iZone.”

Not all of the top teachers recruited to the iZone came from high-performing schools. About a fourth left other struggling schools known as “priority schools,” which are academically in the state’s bottom 5 percent. (iZone schools are “priority schools” too.) So the researchers also looked into the impact on priority schools that were left behind — knowing that teacher turnover is more harmful for lower-achieving schools. They found that the effect was even smaller than on non-priority schools, possibly because they usually lost a single teacher instead of multiple teachers.

“It could have been a more negative scenario,” Henry said, “if teachers were simply being pulled from one priority school to another in the iZone and the students in schools that were left behind were losing.”

FIVE YEARS IN: Tennessee’s two big school turnaround experiments yield big lessons

You can read the full research brief below:

Clarification, February 1, 2018: This story has been updated to clarify that the Tennessee Research Alliance is a partnership of Vanderbilt University and the Tennessee Department of Education.