Read the list of grants made by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative that Chalkbeat has compiled.

In late 2015, Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan promised to donate 99 percent of their Facebook shares to their philanthropy, which would focus part of its work on improving American education.

In the three years since, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative has given away millions to groups working to “personalize” learning, reshape teacher training, and diversify the ranks of education leaders. But the full scope of that giving hasn’t been clear.

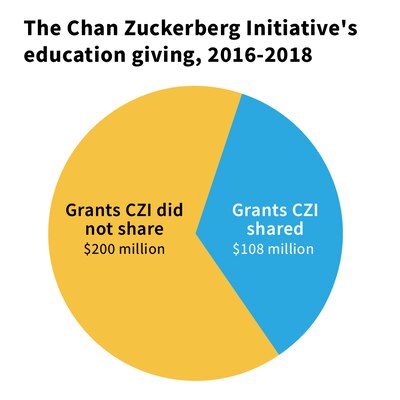

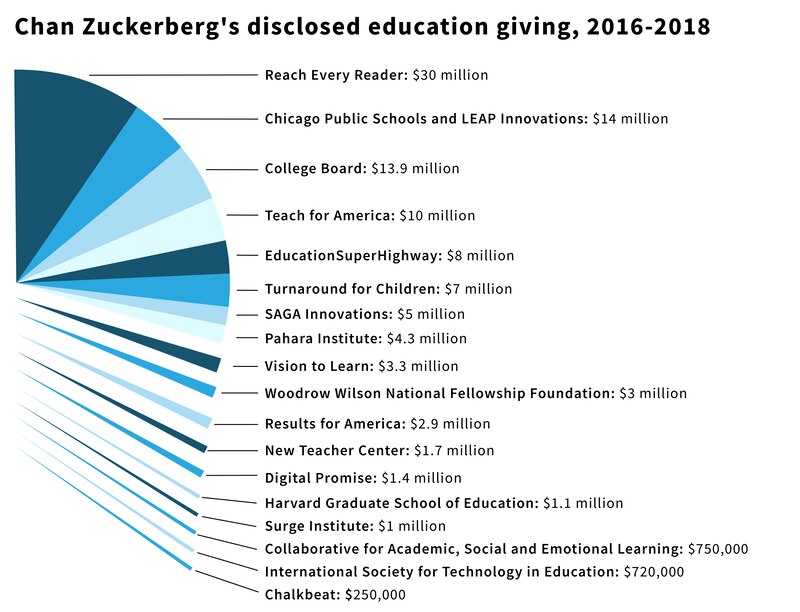

Now, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative is putting a number on it: The organization has given $308 million in education grants since January 2016, when CZI took its current form. After inquiries from Chalkbeat, the organization provided that total, which has not been previously disclosed, as well as details of 19 specific grants.

The numbers offer new perspective on a philanthropy that has quickly become one of the biggest in U.S. education, thrusting itself into the ongoing debate over the appropriate role for private dollars in education policy. They also offer hints about how broadly CZI may try to extend its philanthropy in the years to come, as Zuckerberg’s billions position the organization to become even more influential. The Facebook founder, whose net worth is currently estimated at over $60 billion, is poised to transfer up to $13 billion to CZI by early 2019.

“Even given the fact it can be hard to pinpoint every dollar over time, $308 million over nearly three years would pretty easily make CZI a top-five grantmaker in pre-K-to-12 education,” said Jeff Snyder, a professor at Cleveland State University who has studied education philanthropy. Available data suggests that CZI’s donations may put it behind only the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation, he said.

(Chalkbeat receives support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and other funders mentioned in this story, including the Gates Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation, and the Emerson Collective through the Silicon Valley Community Foundation.)

CZI’s education work is at an inflection point. Its head, former Obama administration official Jim Shelton, said in July that he was leaving the post. His replacement stands to become one of the most influential figures in education policy.

As for its past giving, CZI is being more open than it has ever been by providing the new data. But the organization remains one of the least transparent funders in education.

Unlike a number of other philanthropies, CZI does not publicly list its grants, instead announcing only certain awards on Facebook or in press releases.

The 19 grants that CZI disclosed to Chalkbeat account for about one-third of the $308 million it has spent on education.

As a limited liability company, CZI is not required to list donations on its tax forms, unlike private foundations. Still, the organization says its approach is changing. “We have begun sharing our learnings to date with the education community and news media as part of our commitment to transparency,” spokesperson Dakarai Aarons said in a statement. “As we continue to build our strategy and systems, we plan to share more information about our grants in the future in a way that respects our grantees and community partners.”

Based on the information from CZI, details provided by other organizations, and publicly available information, Chalkbeat compiled its own list of over 50 groups that have received grants from CZI since 2016. Of the $308 million CZI says it has given away, Chalkbeat was able to account for roughly 45 percent. (Find our full list here.)

A push for tech-based personalized learning

The organizations receiving money from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative illustrate the scope of CZI’s efforts to personalize learning, the central focus of its known education giving. Shelton of CZI has suggested that the approach can produce massive gains in student learning; research hasn’t backed that up so far, but some programs have shown promise.

CZI’s giving includes expanding the use of technology in schools so that students can learn at their own pace or teachers can closely track student progress. CZI has also defined personalized learning as including “social-emotional and interpersonal skills, mental and physical health, and a child’s confident progress toward a sense of purpose,” as Shelton put it in 2017.

CZI has funded personalized learning efforts directly in a variety of places: statewide in Rhode Island ($1.5 million), in more than 100 Chicago-area schools ($14 million), and in a small district in California, Lindsay Unified ($775,000).

It has supported personalized learning-focused work by leadership groups Chiefs for Change ($3 million) and the Council of Chief State Schools Officers (nearly $400,000).

This includes the 19 grants that CZI provided details about to Chalkbeat.

CZI has backed efforts to infuse the concept into teacher training, including through the Woodrow Wilson Teaching and Learning Academy ($3 million), the New Teacher Center ($1.7 million), and the Harvard Graduate School of Education ($1.1 million).

CZI teamed up with the Gates Foundation to each send about $6 million to New Profit, which used that money to fund groups including iNACOL, an online learning association, and Valor Collegiate, a Tennessee-based charter network that uses a curriculum that students move through at their own pace.

CZI has built a unique relationship with Summit Public Schools, a charter network in California, which created a tool known as the Summit Learning Platform. Now being used in hundreds of schools across the country, the platform got early engineering help from Facebook and gets ongoing support from CZI.

Both CZI and Summit declined to say how much CZI has spent supporting the effort, though the details of their partnership form a long — and likely expensive — list.

Summit schools have received CZI money to launch and operate a teacher residency program and to buy and build school facilities, according to a Summit spokesperson. CZI support also allows the network to distribute its learning platform to schools, put on three free trainings each year for more than 2,500 educators, and pay for mentors who coach schools using the platform.

Expanding the definition of personalized learning and the pipeline of leaders

CZI has also supported efforts to give poor children eyeglasses through Vision to Learn ($3 million) and a partnership that includes Community in Schools ($2.2 million).

One of CZI’s priorities has been expanding what we know about how students learn, and it’s backed research on the science of learning by both the Learning Policy Institute and Turnaround for Children ($7 million).

It has funded initiatives focusing on non-academic skills, including the Character Lab — led by Angela Duckworth, the professor who popularized the concept of “grit” — and the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning ($750,000).

CZI awarded $750,000 over two years to Common Sense Media to review the privacy protections offered by education technology products.

The College Board won nearly $14 million for initiatives including expanding access to SAT practice using Khan Academy; an expansion of AP computer science courses, particularly in rural areas; and a college advising program.

CZI has also placed a major emphasis on growing the number of leaders of color in education, with grants to Teach For America ($10 million), The Surge Institute ($1 million), Camelback Ventures, Education Leaders of Color ($300,000), and Latinos for Education.

CZI has supported media and communications ventures, too, including personalized learning and other coverage at EdSurge (at least $700,000), a video series on social and emotional learning by Edutopia ($500,000), and “future of learning” coverage by The Hechinger Report. Education Post, a communications firm and blog, netted $1 million from CZI, half of which went to its California-focused outlet. Chalkbeat received a $250,000 grant from CZI in 2018; the grant is not for a coverage of a particular topic.

The grants illustrate how Chan and Zuckerberg have adjusted their approach since their first major foray into education philanthropy, a $100 million gift to Newark schools in 2010. Used to expand charter schools and implement a performance pay system for that city’s teachers, the donation proved deeply controversial.

Although CZI has given to traditional districts, other grants remain tied to charter schools. In addition to its work with Summit, it has donated to the Charter School Growth Fund and given at least $5 million to New Schools Venture Fund, which supports charter schools and efforts to grow the number of leaders of color in education. Achievement First, a charter network, got $350,000 for its “Greenfield” schools, which have an online learning component.

Meanwhile, CZI continues to be involved in Newark. Chalkbeat reported last month that CZI provided funding meant to ease the school district’s transition from state to local control.

Big influence but limited transparency

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s recent giving vaults CZI into the top echelon of education funders, though it remains behind the Gates Foundation and Walton Family Foundation for now. Whereas CZI averaged a bit over $100 million in grants each of the last three years, Walton spent $191 million on U.S. education programs in 2016 and the Gates spent about $367 million.

That kind of funding is dwarfed by the public dollars spent on education. But philanthropic money can have an outsized influence on policy: think the rapid spread of teacher evaluation changes, the Common Core standards, and charter schools, all catalyzed by funding from major philanthropies in the last decade.

For now, the entirety of CZI’s grantmaking strategy is unknown. A number of organizations that Chalkbeat contacted declined to say how much money they’ve received from CZI or whether they have received funding at all.

That level of transparency differs from the two biggest foundations in U.S. education. The Gates Foundation has a searchable database of grants going back many years. The Walton Family Foundation posts annual giving reports reaching back to 2009. Other philanthropies, like the Broad Foundation, are somewhat less transparent — listing current grantees but not amounts, for instance, though more detail can be found on tax forms.

Chan Zuckerberg differs from those foundations in key ways, some reflecting changing preferences among philanthropists.

Unlike the Gates, Walton, and Broad foundations, CZI is a limited liability company. That allows it to make political donations, invest in for-profit companies, and not disclose the compensation of its top leaders. CZI is not alone in this approach: The Laurene Powell Jobs-funded Emerson Collective is also an LLC.

CZI says it has not made political donations pertaining to its education work. It has invested in a number of for-profit businesses, though, including RaiseMe, a software platform aimed at helping students access information about college scholarships; Ellevation, a product to help teachers of English language learners; and Panorama Education, which provides student surveys. Any profit earned will be put back into the organization, CZI says.

“Just constraining yourself to only nonprofit giving cuts off a lot of good options,” Zuckerberg told Education Week in 2016. “I believe that companies can do a lot of good stuff in the world.”

A complicated funding web

Adding a layer of complication, CZI has given much of its $308 million in education grants through a “donor-advised fund” at the Silicon Valley Community Foundation — an increasingly popular but controversial strategy offering tax benefits for funders and little transparency.

Such community foundations allow donors to reap substantial tax benefits by donating stock; Chan and Zuckerberg have given the Silicon Valley Community Foundation about $1.75 billion worth of it. CZI directs the community foundation to make grants, and those donations are listed on the community foundation’s tax forms and its website.

But, crucially, those disclosures don’t indicate which fund makes which donation — meaning grants directed by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative through SVCF are not distinguishable from those made by more than 1,000 other funds.

For instance, the Silicon Valley Community Foundation lists $35 million, $20 million, and $16 million grants made to Summit Public Schools in 2016 and 2017, but offers no information on which fund made the donations.

The result of this trend? “Even as we’ve entered a period in which more donors are writing bigger checks to promote this or that cause, it’s become ever harder to follow the money,” Inside Philanthropy editor David Callahan wrote in a 2016 piece highlighting the rise of donor-advised funds. (He praises the Silicon Valley Community Foundation’s database of grants, while noting that it “doesn’t give us any clue” who is behind the donations.)

Those donor-advised funds also do not have to give away a specific share of their assets each year, unlike private foundations, which must donate 5 percent — a setup that has prompted criticism that they allow money meant for charity to sit idle.

To defenders, these funds are just a new vehicle for helping nonprofits improve their communities. The Silicon Valley Community Foundation says its donor-advised funds with more than $1 million pay out an average of over 15 percent each year.

Snyder of Cleveland State University said this new breed of philanthropy raises fresh questions about how groups like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative will use their influence.

“Traditional philanthropy from private foundations has been critiqued for being anti-democratic, yet LLCs such as CZI have opportunity to be even more emblematic of this concern,” he said.

“That’s really the question: Can LLCs simultaneously be freed from constraints that are supposed to ensure they work in the public interest, and evolve into institutions that democratically work with communities they seek to shape?”

Amanda Zhou contributed reporting. Graphics by Sam Park.