When Ted Finn first heard about the new way of running a high school, he was excited.

Forget students squeaking by with Cs and moving on without truly understanding math or biology. Throw out the idea that a student has to pass a collection of classes to earn a diploma — instead, tell them what essential skills they need. Instead of letting a bad test grade derail a student, give them multiple chances to demonstrate what they know.

“The idea of having an identified set of standards and expectations that would be put out there, so that … everybody would know that if you had earned credit in, say, an Algebra I class, you did in fact meet specific identified standards — at first I was thinking, this is great,” said Finn, a longtime Maine educator and the principal of Gray-New Gloucester High School, about 20 miles from Portland.

For the last several years, he has been part of an ambitious experiment to take that approach, known as proficiency-based education, statewide. In 2012, Maine passed a law changing how high school diplomas were awarded. To earn one, students would have to demonstrate that they had mastered material in eight subjects. Advocates said this would better prepare students to compete in the future economy.

But the latest developments suggest that Maine may become a cautionary tale rather than the successful proof point advocates had hoped for.

Across the state, districts struggled to define what “proficiency” meant and teachers struggled to explain to students how they would be graded. Those challenges, plus strong backlash from parents, caused the state to scrap the experiment earlier this year, allowing districts the choice to return to traditional diplomas.

“If you don’t have the buy-in of your community, you’re in for a world of hurt,” Finn explained.

Maine’s meltdown matters because the ideas at the core of the state’s efforts are influencing states and school districts across the country. Forty-eight states have adopted policies to promote “competency-based” education to varying degrees, often at the urging of a constellation of influential philanthropies, including the Nellie Mae Foundation, which poured at least $13 million into Maine’s effort.

Meanwhile, new research documents the challenges that beset the effort seemingly from day one. And there remains little evidence that proficiency-based education has boosted student learning, in Maine or elsewhere.

“A lot of folks are looking closely at what’s happened in Maine and trying to draw lessons from it,” said Charlie Toulmin, the policy director of the Nellie Mae Foundation.

Maine schools quickly faced hurdles

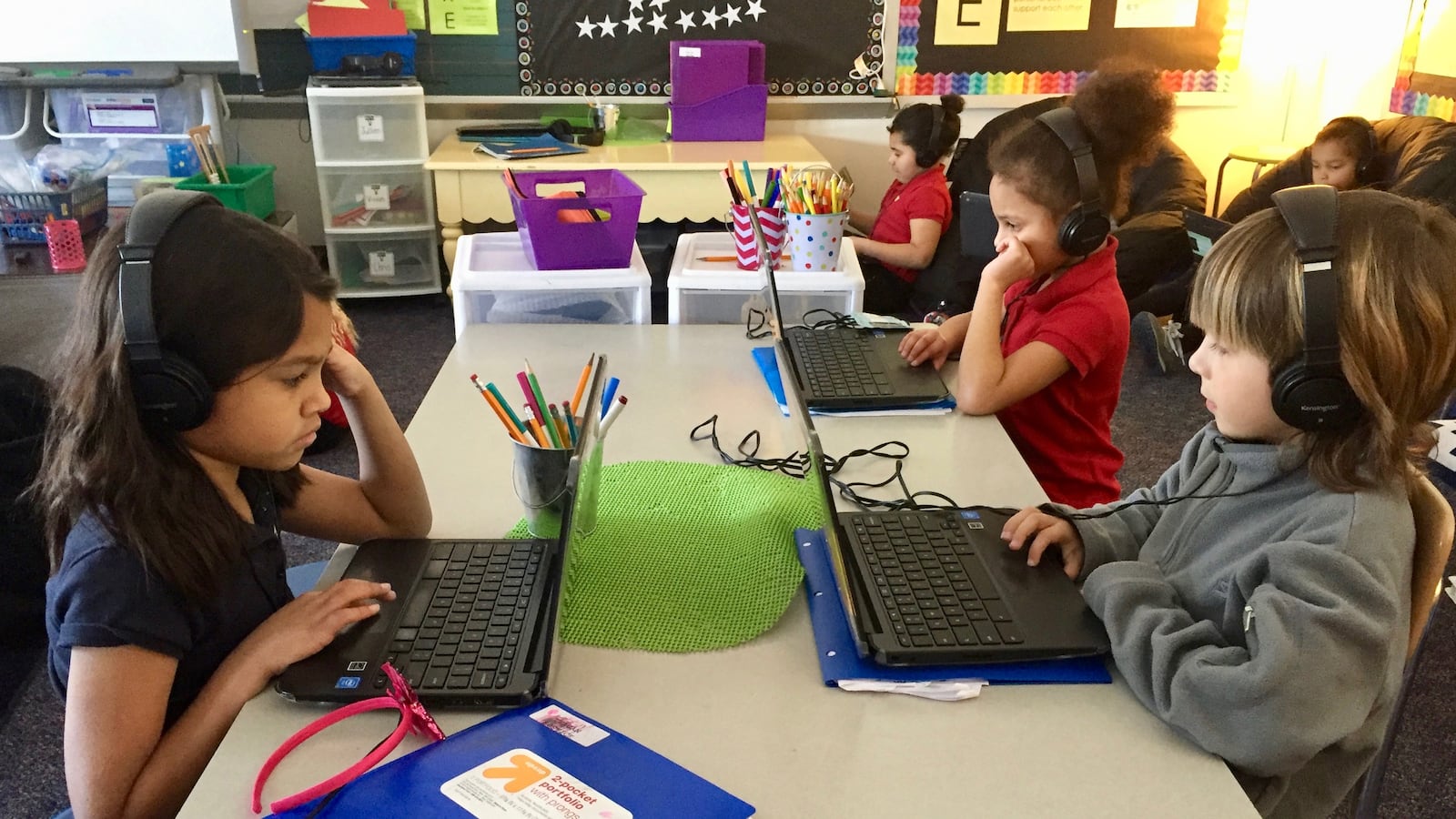

Earlier in 2012, the Massachusetts-based Nellie Mae Foundation awarded nearly $9 million to two of Maine’s largest school districts, Portland and Sanford. The money was meant to help them adopt what the organization calls “student-centered” approaches. That includes what’s called mastery, competency, or proficiency-based learning, which means that students progress at their own pace, moving on only when they demonstrate they’ve learned a certain topic.

Those districts quickly got to work. “Parents may ultimately stop seeing report cards with A, B, or C grades on it and instead start seeing what it is that their student can do,” the Sanford superintendent said.

Those districts’ moves made what came next seem less radical than it might otherwise have. With bipartisan support, Maine lawmakers passed the bill revamping graduation requirements statewide, titled “An Act To Prepare Maine People for the Future Economy.” It required all districts to begin awarding diplomas based on student proficiency in several years.

Then it fell to districts and schools to make sense of the new rules — a complicated endeavor that sometimes meant scrapping key elements of how high school traditionally worked.

Each district was tasked with determining what it meant for a student to be “proficient” in the subjects Maine required. Officials knew that if they set standards too high, an unprecedented number of students could fail to graduate. Too low, and it would defeat the purpose of the whole exercise.

Those questions reverberated in schools, too. Schools weren’t required to change their grading systems, and some held onto their A-Fs. Teachers in many others starting awarding students scores of 1 through 4, with 3 equalling proficient, for each of the key standards.

The law required that students be able to demonstrate that proficiency in a variety of ways, whether through a traditional exam, a portfolio of work, a project, or a performance. But what that meant varied widely between classrooms, creating headaches for students.

Many let students take and retake tests to prove they were proficient, and some stopped grading homework or classwork altogether.

“Each teacher has their own system,” Ellie Roy, a senior at Gray-New Gloucester High School, told the Hechinger Report last year.

Evan Cyr, a high school teacher in Auburn, Maine, said the changes forced him to get “really explicit with students” about the connection between the work they were doing in class and the standards that they would actually be tested on.

At the same time, teachers began evaluating students on things like being a critical thinker or an informed citizen — qualities that were included in the new graduation requirements.

The shifts left plenty of students and parents confused and frustrated. Proficiency was the goal, but doesn’t 3 out of 4 equate to a C? Would out-of-state colleges be able to make sense of the new and confusing transcripts? And how did any of these scores translate into the information that undergirds many of the traditional trappings of high school, like sports eligibility, class rankings, and a valedictorian?

Research, including a series of papers released by the University of Southern Maine and a study funded by Nellie Mae released this month, has examined how a number of districts responded to those challenges.

They found that most teachers continued using traditional exams, not portfolios or performances. Some teachers remained overwhelmed by the prospect of helping struggling students clear the bar without more guidance.

“We’re only till the end of quarter one, and they’re already not able to meet the standards from quarter one of that class, so it’s very concerning,” one special education teacher told researchers. “How is this going to work? And to be honest, nobody really … has a good answer for us.”

Others remained concerned that allowing students to demonstrate proficiency whenever they wanted could have unintended consequences. Cyr said this was the most controversial aspects with parents in his district. “Some of our students have developed some bad habits that are really going to plague them about deadlines,” said one teacher.

A few students agreed. “I just feel like I’m not getting challenged enough because I know if I don’t pass it, I can just do it again and do it again,” one 10th-grader told researchers.

Concerns began mounting among district leaders, too, about how the changes might affect their graduation rates. Since 2011, Maine, like virtually every other state in the country, has seen its graduation rate climb.

“We heard school administrators indicate that their graduation rate wasn’t going to plummet — because they would just change their definition of proficiency,” said Erika Stump, one of the researchers.

Then there was the issue of funding. Districts got a 0.1 percent boost in state funding to implement the law, which in most cases amounted to just a few thousand dollars. This ran headlong into some of the ramped-up graduation requirements, like proficiency in a foreign language. One Maine district resorted to purchasing the Rosetta Stone program after being unable to find French or Spanish teachers.

Nellie Mae tried to fill in some of that funding gap. The foundation has given nearly $9 million since 2010 to the nonprofit Great Schools Partnership to help schools implement the law and to build support for the policy. The state department of education was also supposed to provide support; it created a help website, including a best practices page also funded by Nellie Mae.

But the foundation’s outsize role has drawn criticism. “The proficiency-based diploma law has created a niche market for a special group of education ‘consultants’ with financial backing, mostly from the Nellie Mae Foundation, to dictate to policymakers what a diploma should mean,” one skeptical Republican state legislator wrote in March.

Toulmin of Nellie Mae said the philanthropy wasn’t the driving force some made it out to be. “There was already some energy in different places of the state to do this before any of our support came along,” he said.

It’s unclear whether Maine’s new approach led to better results

Did all of that change help students?

The patchwork of local policies mean it’s difficult to measure just how much instruction in Maine high schools changed. The recent Nellie Mae-funded report found that across 11 high schools, most students still weren’t experiencing much “personalized” instruction.

It did find that students who were exposed to more of the approach had slightly lower SAT scores but a higher feeling of engagement in school, though the study couldn’t show whether the proficiency-based approach was the cause of either one.

As for educators, a survey found that only 18 percent of high school teachers believed that the new graduation requirements “increase academic rigor.” But some did say it pushed them to focus more intensely on struggling students. In a number of places, schools added tutoring and after-school programs to help kids who were behind.

“I want them to meet the standard, and the only way to meet some of those kids is to sit down one-on-one,” one math teacher told researchers. “I’ve done a lot more conferencing, and a lot more walking around the room, and a lot more helping them than I have before.”

Any educational successes, though, weren’t enough to keep the experiment from becoming a political failure.

Earlier this year, talk of changing the law attracted hundreds of comments from parents and teachers, sometimes spurring fierce protest.

The state legislature soon conceded. Lawmakers repealed the requirement that districts issue proficiency-based diplomas in June — before a single class of students statewide was required to earn them. Maine Governor Paul LePage, who backed the 2012 law, signed off on the changes in July.

A few districts quickly jumped at the chance to scrap the proficiency-based diplomas.

“Student achievement will be recognized as it has historically been recognized with honor roll, with valedictorian, salutatorian, top 10 percent of the class, some of the historical things that we’re familiar with will be in place,” explained a principal in York, Maine.

Other districts have announced they’re going to keep going. The state department of education says it doesn’t have a count on how many districts have moved back to the traditional system.

Finn, the principal at Gray-New Gloucester High, is still optimistic. He wants his district to continue working to get proficiency-based education right, particularly after the time and money that’s already been invested.

“Can you imagine shifting gears?” he said. “We’ve got kids right now, members of the class of 2020, who are under the new graduation requirements.”

Advocates push forward

Proponents of proficiency-based learning argue that none of this reflects flaws in the concept. Maine struggled, they say, because they didn’t introduce the new systems thoughtfully enough, moving too quickly and requiring change rather than encouraging it.

“When there was poor implementation — and there was poor implementation — then of course the parents and the community members start saying, hey, we don’t like this competency-based education,” said Chris Sturgis, co-founder of CompetencyWorks. “But it wasn’t really competency-based education.”

“It is a lesson on the perils of putting a mandate in place and not having organized for the necessary clarity and guidance for the field,” said Toulmin, Nellie Mae’s policy director.

Those lessons matter far beyond Maine. Competency-based education and other related approaches, like “personalized learning,” are spreading across the country, catalyzed by prominent advocates and influential funders. They include the U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, as well as philanthropies like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Laurene Powell Jobs’ Emerson Collective, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. (Chalkbeat is funded by CZI, Emerson via the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, and Gates.)

Many have made arguments strikingly similar to the ones Maine lawmakers used to push for the new graduation requirements — that schools haven’t changed in many years and they need to in order to prepare students for a rapidly changing economy.

Neither of those claims is nearly as clear-cut as advocates contend, and there remains limited research on whether competency-based or personalized approaches boost students’ success in school. Existing studies have often focused on schools that are best poised to implement such changes and have generally found small to moderate learning gains.

“A lot of it says: The reality is that there is some initial early results, and that we don’t know enough,” said Eve Goldberg, the director of research at Nellie Mae.

Today, almost every state support proficiency-based education in some way — a number that has increased dramatically since 2012, according to CompetencyWorks. Fifteen districts in Illinois are participating in a competency-based high school graduation pilot program. In Arizona, students can opt to earn a proficiency-based diploma. Examples of schools and districts trying the approach also exist in Indiana and Colorado, among others.

The concept has particularly taken hold in the Northeast, often with funding from Nellie Mae, which focuses on the region. New Hampshire now requires districts to base academic credits on mastery of content.

Most similar to Maine is Vermont, which is set to require students to earn proficiency-based diplomas in 2020. That’s causing pushback there too.

“We are leapfrogging everyone,” one resident said at a Vermont house committee hearing in April. “We are running an educational experiment on our kids based on theory, not proof that this has worked in another state.”