Tennessee has begun accepting applications from families wanting government-funded vouchers to send their children to private schools, even as the new program is mired in a court battle and public schools may lose more funding if the coronavirus pandemic causes a recession.

The state education department will accept applications through April 29 via an online site that went live on Friday.

As of Monday afternoon, the families of 338 students had applied for up to 5,000 slots available to receive education savings accounts for next school year in Memphis and Nashville.

The program could grow to 15,000 students by its fifth year, potentially diverting more than $100 million in taxpayer money to private schools under a 2019 law championed by Gov. Bill Lee.

Lee’s decision to move ahead with the launch of the major program amid a state of emergency shows his depth of commitment to introducing more education choices for Tennessee families.

On Monday, the governor shut down non-essential businesses statewide due to the spread of COVID-19. A significant drop in revenue is certain in a state that depends on sales taxes to help fund public schools. Lee’s finance commissioner, Stuart McWhorter, who is now managing the state’s response to COVID-19, has said a recession is likely.

In response to the crisis, the legislature passed a reduced budget earlier this month that slashed hundreds of millions of dollars in investments earmarked for public education. The spending plan kept $41 million for the voucher program to begin this fall, a year earlier than the law required but in keeping with Lee’s order for an expedited launch.

Most of that voucher program money is to offset per-pupil funding losses to school districts in Memphis and Nashville as voucher participants move their children out of public schools. The reimbursement plan is scheduled to end within three years, and lawmakers also could choose not to fund it at all in the second and third years.

Saying that “hard times require hard choices,” Lee told reporters in mid-March that his reduced budget retained funding for any previously passed education initiatives, plus includes a 2% increase toward teacher salaries.

Meanwhile, two lawsuits challenging Tennessee’s 2019 voucher law charge that the program will saddle governments in Memphis and Nashville with an unfair financial burden by transferring state and local funds from struggling public schools to private schools.

Governments in Metropolitan Nashville and Shelby County sued the state in February to block the program. A second lawsuit was filed in early March on behalf of 11 public school parents in those communities. Both suits charge that the law arbitrarily targets Tennessee’s two largest cities — and that resulting shifts in funding will violate the constitutional rights of public schoolchildren to receive an adequate and equitable education. Three pro-voucher groups representing other parents who want to receive education savings accounts have also joined the legal battle.

Chancellor Anne C. Martin has promised to move swiftly in the case and is expected to rule May 22 on two motions that have since been filed in the first lawsuit. The state is seeking to dismiss the case completely, while Metro Nashville is asking Martin for a summary judgment to strike down the law.

The voucher application process is being handled by FACTS Management, a company based in Lincoln, Nebraska, that is a subcontractor to ClassWallet, the vendor hired by the state education department to manage online payments and applications under a two-year contract worth $2.5 million.

“Everything is working seamlessly,” said Deputy Commissioner Amity Schuyler of the application rollout. “No issues, no crashes, no problems.”

However, the pandemic has affected how the department and pro-voucher groups had planned to get the word out about education savings accounts and engage with the parents of eligible students.

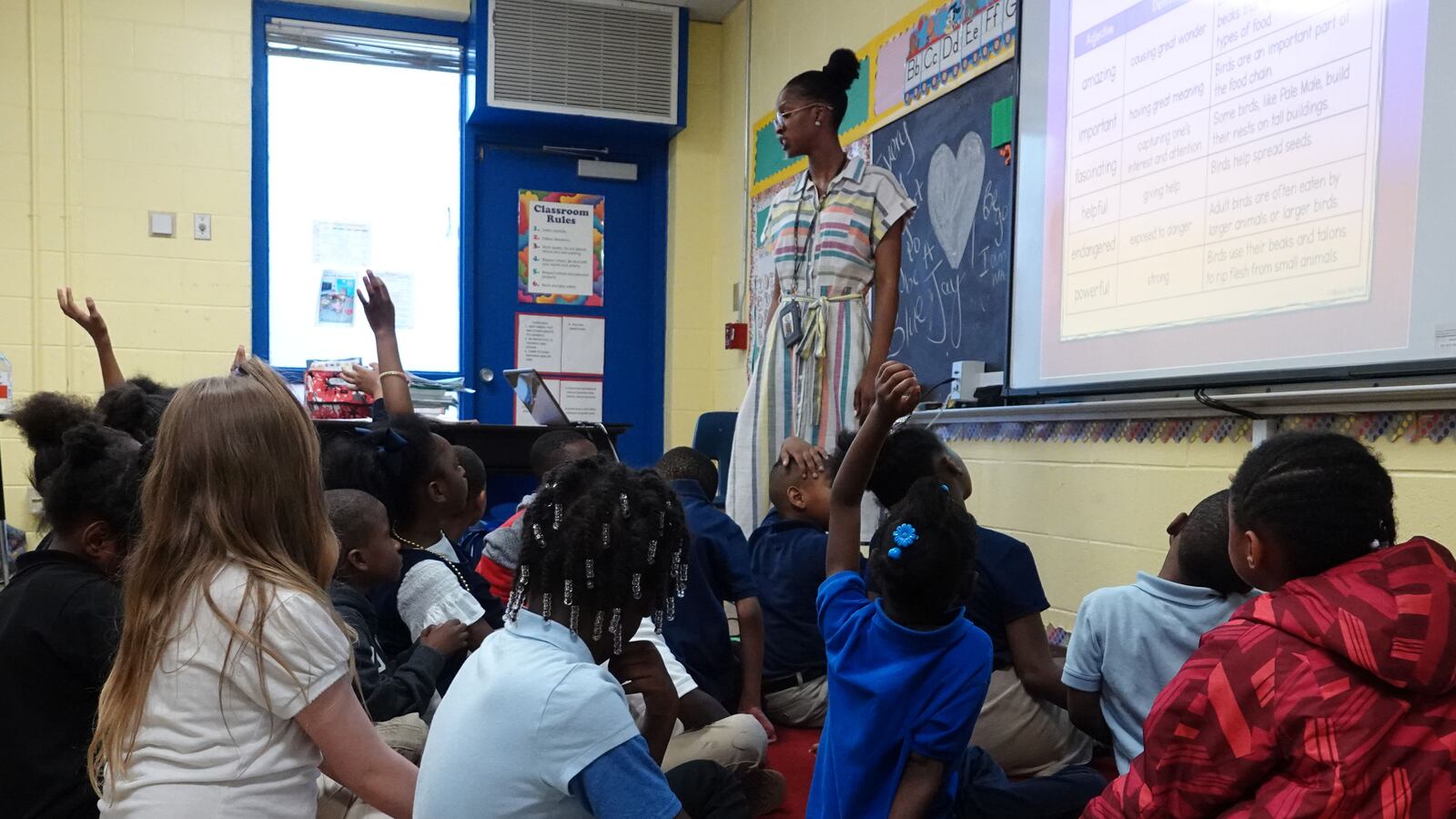

Workshops to speak with parents in public libraries, community centers, and private schools have been canceled. Instead, the state is relying on printed information being mailed next week to 86,000 households whose students receive free and reduced lunches. And Tennessee leaders with the American Federation for Children are moving their engagement efforts online.

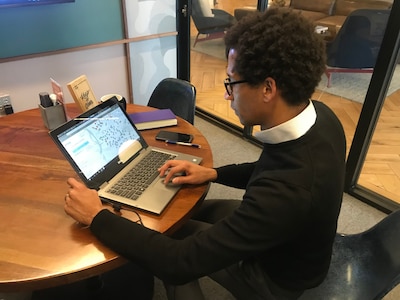

“We’re putting together materials that are easily digestible if you’re looking at your phone — quick videos, for instance,” said Shaka Mitchell, the AFC’s state director. “We’re using services like Facebook Live and YouTube, things that are already out there. It’s much more of a challenge, for sure.”

To be eligible, students must be attending a Tennessee school this school year or entering kindergarten next year and must be zoned for schools either in Memphis or Nashville. The family’s household income also must not exceed double what’s needed to qualify for free lunch under federal guidelines. For a family of four, that’s about $65,000 annually.

Applicants must submit several pieces of documentation that could include a valid driver’s license or state ID, a utility bill, a voter’s registration card, or an affidavit from a landlord.

If approved, students will receive an average of $7,000 to attend one of 55 private schools authorized so far to accept the vouchers, including 25 in the Memphis area and 28 in the Nashville area.

Participating schools must be state-accredited and provide legal assurances that all employees have undergone the same level of background checks required of public schools through the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation.

Families with questions can email ESA.Questions@tn.gov or call the department’s ESA hotline at (855) 828-0754.