A basic tenet of school choice is that families will choose higher-quality schools when they can, spurring schools to improve in order to compete for students. Bad schools will fail the grueling test of the market, while good ones will thrive.

Now a new study raises questions about this basic premise.

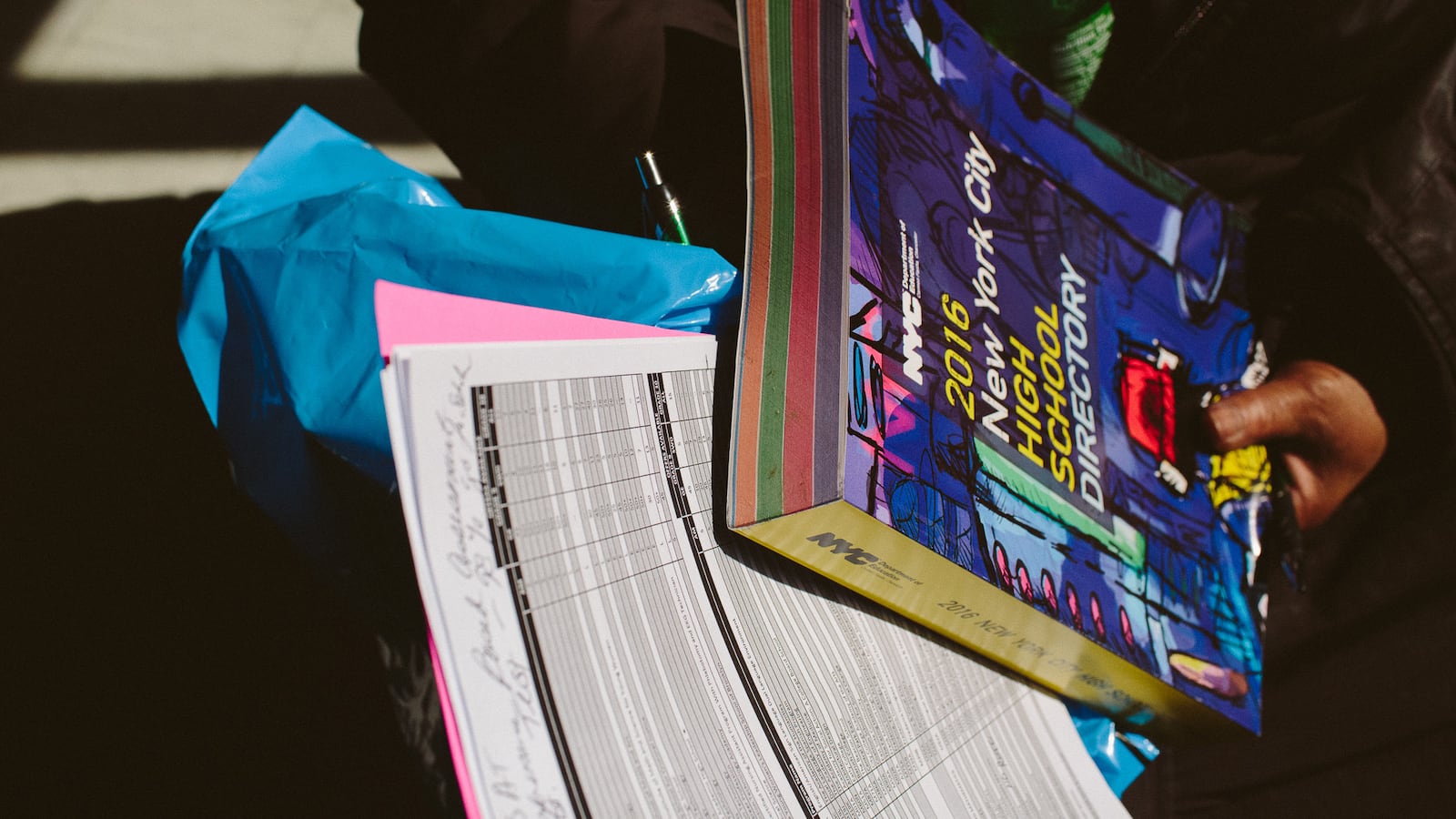

The analysis examines high school choice in New York City, where students in district schools have a bevy of options and can attend schools outside their neighborhood. But families aren’t flocking to the most effective schools — they are looking for schools with higher-achieving students.

“Among schools with similar student populations, parents do not rank more effective schools more favorably,” write researchers Atila Abdulkadiroglu, Parag Pathak, Jonathan Schellenberg, and Christopher Walters. “Our findings imply that parents’ choices tend to penalize schools that enroll low achievers rather than schools that offer poor instruction.”

The result: school choice programs may incentivize schools to do more to attract students more likely to perform well, not help students learn more.

It’s a strong indictment of the theory behind school choice, though the research — like any single study — is hardly definitive. Prior studies on vouchers and New York City charters have shown that district schools generally see (small) increases in test scores when parents and students have more choices about what school to attend. Charter schools in several states have improved over time, which may be evidence of choice and and competition working.

But the study highlights some of the often-unspoken factors that drive school choice and how schools, in turn, are likely to respond.

Peers trump school quality in the eyes of families

The paper, which has not been formally peer-reviewed and was released through the National Bureau of Economic Research, examines how families of eighth-graders chose public high schools in New York City between fall 2003 and spring 2007.

Because the city allows students to rank many district high schools, and then assigns them one, the researchers have a treasure trove of data to draw from. (The latest analysis does not examine charter or private schools.) The study then connects how students ranked schools to metrics like test scores, high school graduation, and college attendance.

It is true that better schools — defined as schools improving those specific outcomes — are ranked higher, but that seems solely due to the fact that those schools also have higher-achieving students. Comparing schools with similar students, better schools don’t get a boost in parent demand.

“Our findings imply that parents’ choices tend to penalize schools that enroll low achievers rather than schools that offer poor instruction,” the authors write.

Perhaps surprisingly, there is not much evidence that schools that seem to do better with certain groups of kids are more likely to attract those students. In fact, schools that are particularly effective with low-achieving students tend to be especially popular with high-scoring kids.

It’s not clear which interpretation of the results is correct

There are a number of ways to interpret these results.

One, is that families value characteristics — like safety or after-school programs — besides the metrics of school quality used in this study. That said, the study includes measures like high-school graduation and college attendance, that parents and students are likely to care about.

Another hypothesis is that families and students simply don’t have good data on which schools are good.

“Without direct information about school effectiveness … parents may use peer characteristics as a proxy for school quality,” the study suggests. Indeed, there is evidence that families respond to information about school performance, but it’s unclear to what extent they would prioritize sophisticated measures of school quality, even if given that additional data.

Perhaps families are simply more concerned about peers than schools. Families may consider the types of students at a school as a proxy for school success — something that might be deeply ingrained and difficult to overcome. It may also be due to biases, including racism.

This, the authors suggests, has troubling implications for policy.

“If parents respond to peer quality but not causal effectiveness, a school’s easiest path to boosting its popularity is to improve the average ability of its student population,” the paper says. “Since peer quality is a fixed resource, this creates the potential for … costly zero-sum competition as schools invest in mechanisms to attract the best students.”

Want to learn more about NYC high schools? Come to Chalkbeat’s event this Thursday on how to make the high school admissions process more fair. Also be sure to sign up for Chalkbeat’s national and New York newsletters.