Leer en español.

During this Hispanic Heritage Month, Alicia Jones-Lumbuz’s Houston classrooms came alive with folk songs from Nicaragua and renditions from the musical, “In the Heights,” set in Washington Heights, a New York City neighborhood home to many Dominican Americans.

The masked, in-person performances were sweeter, albeit quieter, than the Zoom performances of the previous two years.

“We’re still learning to get loud,” Jones-Lumbuz told Chalkbeat. “This has been such a difficult season for everyone, especially our children. They are coming back into schools now quiet, unsure of themselves. I want them to sing out and be proud of who they are. I want them to see themselves in our songs.”

Oct. 15 marks the end of Hispanic Heritage Month. Chalkbeat spoke to Hispanic and Latino teachers and students around the nation about how they are celebrating their cultures and navigating this season of loss. Hispanic and Latino populations across the nation have made up a disproportionate number of deaths from COVID-19, and the pandemic exacerbated existing inequities for Hispanic and Latino students — widening education gaps and spurring drops in college enrollment.

For students like Ines Adriana Martinez, the pandemic upended college plans due to new caregiving responsibilities.

“I got accepted into UC Davis, but I decided to stay local and do community college, and then transfer,” said Ines, now a sophomore at Cabrillo College in California. “Because of this whole pandemic, I became more financially responsible, not only for myself but also for my family. And I realized how much I knew nothing. I wanted to know more.”

Below, Ines’ story and others’ are interspersed with poetry and artwork from students across the country. These excerpts have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

At Chalkbeat, we know the stories of Hispanic and Latino students and educators should be told all year long, not just during Hispanic Heritage Month. Do you have a story idea for us? A student or educator that should be highlighted? Email us anytime at community@chalkbeat.org.

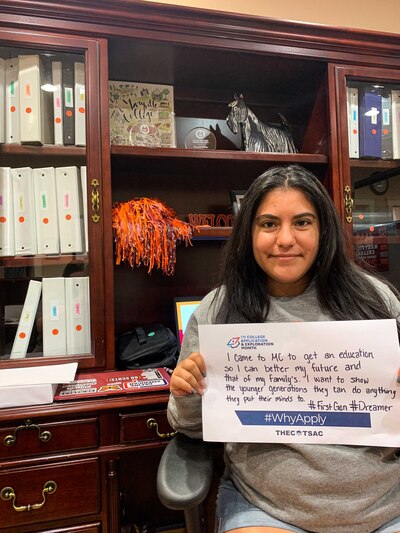

Alexa Maqueo-Toledo, 21, Maryville, Tennessee

Senior, Maryville College

I was born in Mexico City and moved to Tennessee when I was in elementary school. For as long as I can remember, it was me and my mom. When my grandmother got sick in March 2020, my mom was the only one who could easily move back to Mexico and care for her. We knew being apart would be difficult — but we didn’t fully understand then what the pandemic was going to do to the world. We use Zoom all the time for conversations and family gatherings, and we’re trying to get her set up to come for my graduation in May, but that feels like slim chances.

So much of my life and my choices have been tied with my [immigration] status as a DACA recipient. I found out about my status when I was 14 and tried to get a driver’s permit with all of my friends. That’s when my family told me. I grew up in the immigrant community, my aunt was involved, my mom taught English classes. I watched firsthand families being torn apart through deportation. I always wanted to go to college, but with the news of my status dimmed that dream.

My senior year of high school is when it really hit. I had to apply to some colleges as an international student, and I didn’t qualify for significant state scholarship programs or in-state tuition. Thankfully, I had a great guidance counselor who didn’t let me give up — and I applied to Maryville, which at the time had recently partnered with [a scholarship organization for Dreamers], Equal Chance for Education.

When I arrived at Maryville, a small liberal arts college, the school’s first openly undocumented student was in his senior year. He served as a mentor to me, and I’m proud to say 15 of us will be graduating this year. We’re getting matching stoles for graduation. And we’re working hard to make the path easier for those who come after us. Tuition equity is one of my missions in life. My passion lies in immigrant, and undocumented youth, in particular, being able to obtain state tuition and state aid as any other Tennessee high school senior. They shouldn’t have to jump through the hoops that I had to or face the challenges that I was able to navigate thanks to my high school guidance counselor.

When many people picture “undocumented,” they think of criminals. They don’t think of the girl you took to soccer practice when your kids were young. They don’t think it’s the people your family grew up with. They don’t think of a girl moving mountains to try to further her education, to contribute. I want them to see me.

Alicia Jones-Lumbuz, Houston, Texas

Choir director and district content lead, KIPP Texas Public Schools: Houston

I have taught choir for over 23 years — and I’m used to my fifth through eighth graders bounding into class, ready to sing, and often leaving me exhausted after corralling their incredible, chaotic energy. Not this year. Many of my students have been going through this pandemic since they were in third grade, and their energy is low.

They barely smile, their speaking and singing voices are very soft, and when we work on choreography, their movements are very lethargic. I have a few students who are happy to be in person — their energy is high, and they have difficulty calming down after completing fun activities or singing. I welcome their excitement and joy to surpass the quiet.

I know my students need my classrooms to be a safe place to process this year — to process the grief of losing loved ones during the pandemic or to navigate in-person environments that feel new and scary. But even before the pandemic, I knew how to create an environment in my classroom where students could process big questions around their identity. I remember what it was like to be in elementary school and have other students ask me, “What are you?” I didn’t look like the Hispanic kids in Florida, where I spent part of my childhood, and I didn’t look Black enough. I certainly didn’t look white. So, what was I? My parents — from Puerto Rico and Jamaica — provided a very encouraging space for me to process these questions, and I now offer that same encouragement to my students.

Our school systems and leaders need to understand that Hispanics are not monoliths. I bring the pride of my roots, especially for Afro-Latino students who may not feel seen or accepted. To celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month this year, I wore a shirt that read: Taino, African, and Spanish. I explained to my students that the Taino are the Indigenous people of Puerto Rico and the Caribbean, that Africans were taken to Latin America to be slaves, like what happened in the United States, and how Spain and other European countries colonized Latin America. I told my students that without these three cultures, I would not be the person I am today.

You see, my Indigenous ancestors gave me the character to be humble, creative, loving, giving, patient, wise, and able to make music. My African ancestors gave me strength, spiritual wisdom, persistence, and a love of rhythm. My Spanish ancestors gave me vision and taught me how I could destroy lives when I let greed and selfish ambitions drive me. My Spanish ancestors also gave me the love of flowing melodies. Without any of these ancestors, the Hispanic and Latino cultures would not exist. Without any of these cultures, infectious Latin American music and hip-hop would not exist. The aim of these lessons was for all of my students, especially my brown and Black students, to stand proud of all their roots, be proud of their ancestors, and love who they are.

Ines Adriana Martinez, 19, Santa Cruz, California

Sophomore, Cabrillo College

Before COVID, I used to do a lot of folkloric dancing. It was very exciting to learn more about my heritage, my background, and the history of Mexico, where I’m from. It just felt empowering. There’s one local event called the Guelaguetza; it’s more like a Oaxacan, Indigenous-type of performance. With the music and with the dancing, it all just looked so beautiful.

Because of the pandemic, a lot has changed. I got accepted into UC Davis, but I decided to stay local and do community college, and then transfer. I wanted to stay home and help out.

I’m the oldest and I had to look after my younger sister. That was a lot to balance. Not only was she attending online school, but so was I. I kind of had to make my schedule around hers. She’d get distracted, and I’d have to tell her to pay attention or make sure she was on camera. I would do my homework in the afternoon, and I’d try to take her outside to the park to get a walk. We all kind of needed that. She would just be more sensitive, angrier, shyer in virtual school. We sought counseling from the school for her, and it helped.

When I started college virtually, I felt a little lost. I quickly discovered that I did not like being on a computer for very long. I just felt tired and had no energy to do anything. It would have been very helpful for them to provide more mental health resources, like free access to someone to talk to. That would have helped me because I was very stressed.

My mom worked all throughout the pandemic; in fact, I think she worked a lot more [than usual]. She works at a tea factory. My dad works in construction, and he didn’t work for a while, so my mom was like the full provider. I noticed she was really stressed. She would leave, and my sister and I would still be sleeping. I would do all of the extra work at home, like chores, cook, and look after my sister, but not like in an ‘Ugh, my god, I have to do this. I don’t want to but I have to.’ Not really. It was more like: ‘I’m going to do this because that’s my new job. I’m helping my mom, I’m helping my dad, and I’m a member of this whole team.’

I think that there is a beauty in the struggle because you’re able to appreciate what you have a lot more and also focus — like have a plan to achieve what it is that you want. Not only that but to have backups, because you never know.

Right now, I’m studying business administration. Because of this whole pandemic, I became more financially responsible, not only for myself but also for my family. And I realized how much I knew nothing. I wanted to know more. I have an aunt, and she has her own business. It’s a daycare program that she runs, and I think that’s such an amazing idea. I’ve always liked the idea of being my own boss, a girl boss.

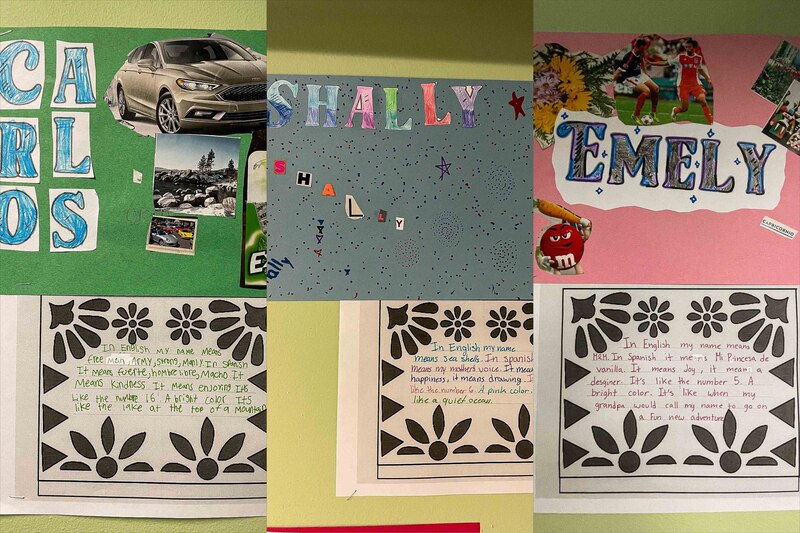

Dennis Martin, Newark, New Jersey

Kindergarten teacher at KIPP Spark Academy

One of the hardest things I witnessed as a student-teacher last school year was parents with language barriers having a hard time logging on their children for remote learning. There was frustration, desperation, and concern. All they wanted was for their kindergarteners to get every minute of instruction they could, even if it had to be through a screen.

As the only Spanish-speaking teacher in a classroom of mostly Latinx students, I was proud to be there for these families during a time of high anxiety as many of them were experiencing the relentlessness of COVID-19. Whether it was guidance with logging on and disabling pop-up blockers so that their students could take a test, or interpreting during parent-teacher conferences, I was able to help in a big way.

But the most meaningful way I was able to support my students was by creating a safe space for them to embrace their identity and cultural backgrounds.

That safe space comes in different forms, given the tools and resources you have. Last year, through those video conversations, I welcomed students to speak to me with both languages if that was how they felt comfortable expressing themselves. This year, as a first-time kindergarten teacher in person at KIPP Spark Academy, I’ve brought my love of bachata and merengue music and dancing to the classroom.

Showing these elements of my identity and pride in my background as a Cuban and Nicaraguan born and raised in Newark, fosters an environment where Latinx students can also embrace the parts of themselves that bring them joy.

Latinx students don’t often get the chance to see themselves reflected in their teachers. Nationally, only 9% of public school teachers are Hispanic. I know how important it is for these students to have a teacher who’s also their advocate, speaks like them, and sees through a familiar lens.

As we wrap up the celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, I’ve been encouraging my students to display pride in their own cultures, even if they are not Hispanic or Latinx. On Oct. 1, KIPP Spark Academy held a parade to honor Hispanic Heritage Month, and students participated by making homemade maracas, shaking them, and dancing to music. As I looked on, I felt a wave of pride all over again as my youngest students laughed and danced along. In that moment, I knew that it’s also a valuable experience for me to see myself reflected in my students. Watching them express this Hispanic and Latinx pride, they may not know it now, but it meant a lot to me.