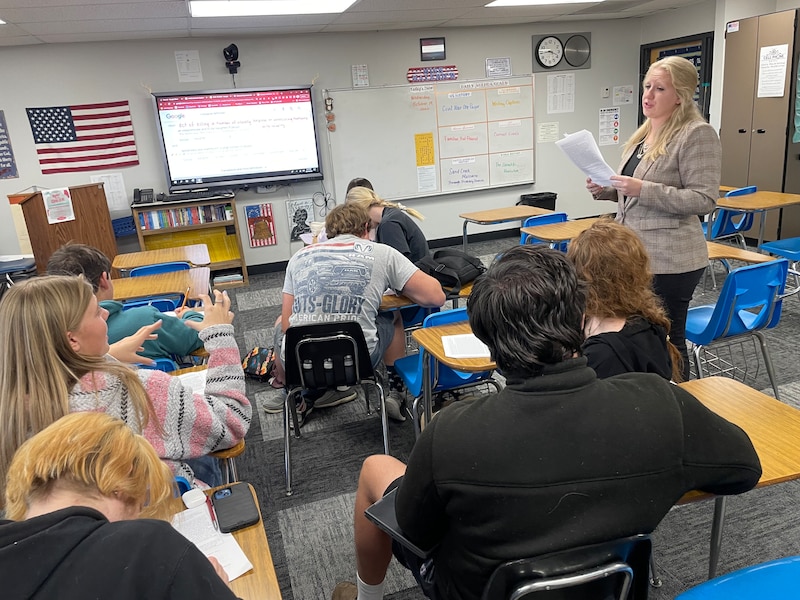

Teacher Sarah Malerich read a letter to the students gathered in her history classroom in the southeastern Colorado town of Kiowa.

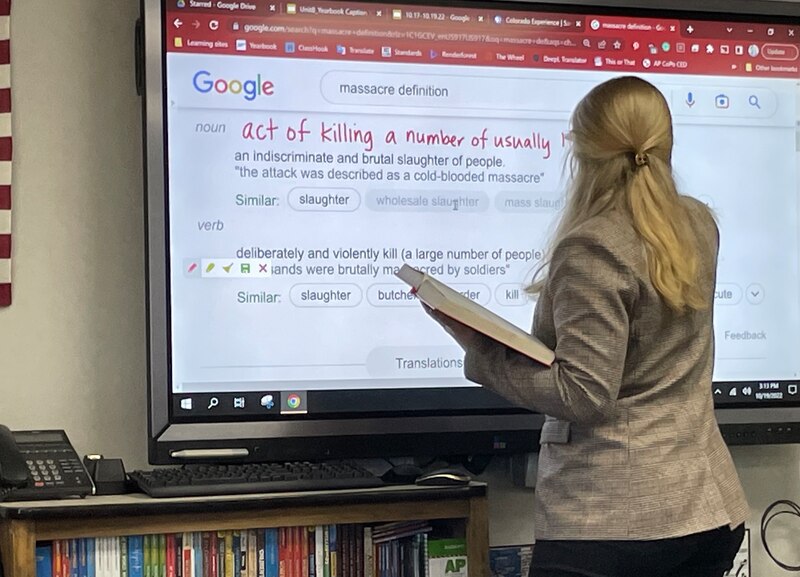

The eyewitness account described how U.S. soldiers attacked a peaceful creekside camp at daybreak, killing more than 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho villagers.

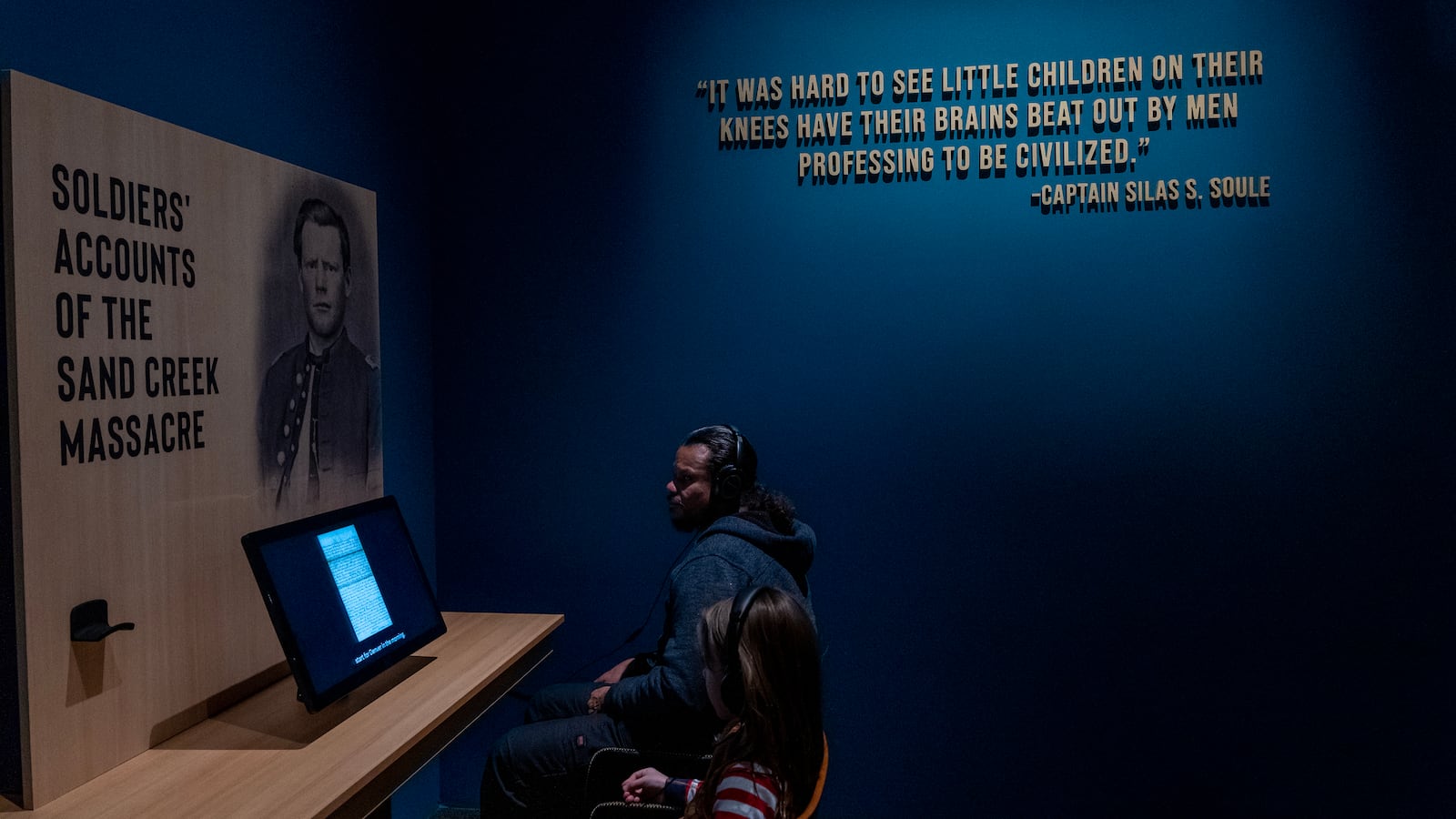

“It was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized,” Malerich said, quoting the letter.

Students murmured “oh my God” and “geez” as Malerich read about the atrocities — the most graphic of which she’d excised. In that moment, the horrors of the Sand Creek Massacre, which unfolded on Colorado’s Eastern Plains more than 150 years ago, became uncomfortably real.

“I’m so upset with history,” said Mariah Vigil-Gonzales, a 17-year-old junior at Kiowa High School. “I wish we had a time machine.”

Other students quickly chimed in, imagining how they could change the events of that long-ago November day. A girl said, “Expose Chivington,” referring to the colonel who led the attack.

So much about the classroom scene was unusual. Few Colorado students learn much about the Sand Creek Massacre — the deadliest day in Colorado history — and even fewer spend several days studying the topic as part of a Native American history class as Malerich’s students did.

The new course is timely, coming as efforts to commemorate and elevate the Sand Creek Massacre are gaining steam across the state. Colorado’s history museum in Denver unveiled an exhibit on the massacre this month, and earlier this fall, federal officials announced a major expansion of the national historic site marking the massacre — about a two-hour drive from Kiowa. In addition, new social studies standards include the Sand Creek Massacre on a list of genocides that Colorado students should study before graduation.

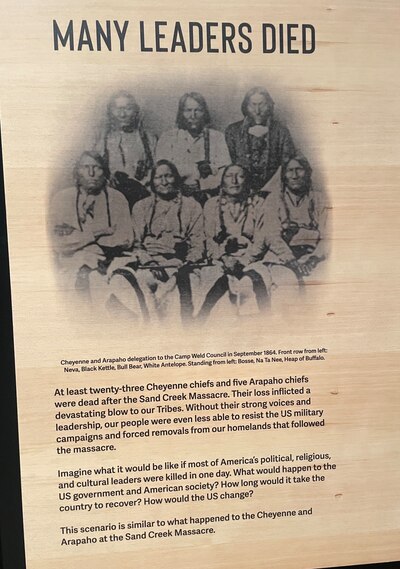

The Sand Creek Massacre occurred on Nov. 29, 1864, when U.S. troops attacked a camp of Native Americans who’d been assured by territorial officials that they’d be safe at that site. Many Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs who’d sought peace with the U.S. government were among the murdered, upending the tribal power structure and fueling decades of war in the West.

“It’s a story that needs to be told. It’s a story that needs to be respected,” said Gail Ridgely, a Northern Arapaho tribal elder who lives on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming.

Ridgely, who is the great-great-grandson of Little Raven, a peace chief who survived the massacre, said the episode contributed to the displacement of the Cheyenne and Arapaho from their homeland in Colorado.

“After the massacre, we were hunted,” he said.

It was only last year that the state formally rescinded the 1864 proclamation that allowed settlers to “kill and destroy” Native Americans and steal their property.

Malerich believes there’s lots of good things to highlight in American history, but that it’s important to teach about shameful episodes like the Sand Creek Massacre, too.

“What can we learn from that?” she said. “We can’t go back and save those peoples’ lives or anything, but what sort of ways can we kind of atone for that?”

Mascot law begets new class

Malerich’s Native American history class exists largely because of a 2021 state law banning Native American mascots in Colorado schools — a measure lawmakers saw as a step toward “justice and healing to the descendants of the survivors of the Sand Creek Massacre, most notably the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes.”

Following the law’s passage, the 318-student Kiowa district, which is crisscrossed by streets with names like Ute Avenue and Comanche Street, sought to retain its Indians nickname. Leaders there asked the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma to approve continued use of the name and mascot, a scenario allowed under the law. The tribe agreed to the request, updating a 2005 agreement, as long as the district met certain conditions, including providing “a curriculum that teaches American Indian History.”

Strasburg High School, which also uses the Indians nickname, and Arapahoe High School in Centennial, which uses the Warriors nickname, have similar agreements with the Northern Arapaho tribe.

The agreement to keep the mascot was “a gigantic win for our community,” said Kiowa district Superintendent Travis Hargreaves. “Teachers are coming with more and more ideas of how we can honor that.”

One of those ideas was the new semester-long history course, which will be a graduation requirement for district students starting with the class of 2025. Malerich said she was excited to launch the class this fall, but also nervous because she wanted to do it justice and couldn’t find many resources designed for high school students.

Students started out by learning about the many tribes that have called Colorado home over the centuries, making maps outlining where each lived. They also discussed the culture and traditions of those tribes, and more broadly, the influence of Native Americans during colonial times and beyond.

“It’s really cool to think about the roots of the land,” said ninth grader Alyssa Edwards, “like, what was here before.”

Several of the 11 students in Malerich’s class — a typical class size at the rural high school — signed up for the new course because they wanted to, not because they had to.

Mariah, who started at Kiowa High this year, said her family is Apache, and she wanted to learn more Native American history. “There’s just a lot of Indians that came through Colorado and so it’s like, a lot of this originated here … and no one ever really talks about that.”

Who learns about the Sand Creek Massacre?

It’s not clear how many Colorado students learn about the Sand Creek Massacre at school — either during their Colorado history unit in fourth grade or any other time.

Representatives from the Colorado Council for the Social Studies and the History Colorado Center in Denver, where the new Sand Creek exhibit opened earlier this month, both guessed the numbers are relatively small.

Hargreaves, who used to be a fourth grade teacher in the Cherry Creek district, said the textbook he used at the time included about a half page on the Sand Creek Massacre.

“It was about a day dedicated to it,” he said.

Malerich, who teaches in the same Kiowa High School history classroom where she once sat as a student, said her first distinct memories of learning about the massacre were not from school but from the TNT miniseries, “Into the West,” which she watched before sixth grade.

Some students in Malerich’s Native American history class said they’d learned a little about the Sand Creek Massacre in other classes. Others never had.

Josie Chang-Order, school programs manager at History Colorado, said there are no children’s books about the massacre and few materials designed for older students either.

“Teachers coming to Indigenous history when we ourselves didn’t get very much of it in schools is a huge challenge,” she said.

She and other museum staff hope the new exhibit will help turn the tide. They’re creating special lessons for fourth- to 12-graders who take field trips to the exhibit and an online list of Sand Creek Massacre resources for educators.

Elishama Goldfarb, whose class at Denver’s Lincoln Elementary includes fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-graders, covers the Sand Creek Massacre at least every three years, interspersing primary source accounts of the massacre with excerpts from a miniseries on Colorado history called “Centennial.”

He wants students to understand the massacre within the context of ongoing conflict, broken treaties, and mistrust between Native Americans and white settlers who wanted gold, land, or other resources.

Goldfarb, who plans to take his students to the new Sand Creek exhibit in January, also connects the prejudice that fueled the massacre to the human temptation to judge people or deem certain people superior to others.

He wants to help students understand that “when we see each other as worthy of dignity and love and care,” horrific events like the Sand Creek Massacre don’t have to happen.

Voices of the people

History Colorado had a Sand Creek Massacre exhibit once before. It closed a decade ago after pressure from tribal leaders, who didn’t feel it accurately reflected their history.

“It was a fairytale, Barbie dolls, misprints,” Ridgely said.

But the new Sand Creek Exhibit — subtitled “The betrayal that changed Cheyenne and Arapaho people forever” — has been done right, he said, with tribal leaders consulted extensively on the details.

“It’s a historic milestone for Colorado and it’s sacred,” he said. “Every time I go down to the museum, it’s a real good feeling because the victims are speaking.”

The exhibit starts years before the massacre, grounding visitors in the tribes’ culture and way of life. Besides maps, timelines, and larger-than-life photos, the exhibit features oral histories from tribe members telling the stories of Sand Creek that have been passed down over generations. The exhibit incorporates Cheyenne and Arapaho language throughout.

Shannon Voirol, director of exhibit planning at History Colorado, believes the new exhibit will help make the Sand Creek Massacre part of the state’s lexicon in the same way the museum’s Amache exhibit raised awareness about the southern Colorado camp where Japanese-Americans were imprisoned during World War II.

“More people now understand that we had Japanese internment camps in Colorado. We get more and more teachers asking about it. We get more students having some knowledge of it. It’s part of the canon as this will become,” she said, gesturing to the photos and artifacts, in the Sand Creek exhibit.

Ridgely, one of several tribe members who worked with museum officials on the exhibit thinks students will become more humble and respectful — “better citizens” — by learning about the Sand Creek Massacre.

In October, Malerich began a series of lessons on the Sand Creek Massacre by discussing the history of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes — their traditions, language, and culture. During the third lesson, she and her students read five accounts of the massacre, including from Col. John Chivington; Silas Soule, an army captain who refused to fire on the Native Americans; and a survivor named Singing Under Water, whose oral account was written down by her grandson.

Malerich read aloud from Chivington’s 1865 testimony to Congress, which falsely portrayed the massacre as a battle where only a few women and no children were killed.

“I had no reason to believe that [Chief] Black Kettle and the Indians with him were in good faith at peace with the whites,” she read.

But students were skeptical and indignant.

“Literally, [they] had the white flag up and the American flag up,” Mariah said of the tribes.

She and her classmates concluded that Chivington knew the Arapaho and Cheyenne were camped peacefully but didn’t care. Other firsthand accounts didn’t support his claims, they said.

After the lesson, Alyssa said knowing how and why the massacre happened might help prevent something similar from happening again.

“That was really inspirational,” responded Brooke Mills, a junior whose mother is partly descended from the Blackfoot tribe. “Like the saying that, if you don’t know your history, you’re doomed to repeat it. I feel like that’s a huge part of all of this, too.”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.