Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

This article was co-reported by Chalkbeat Indiana and Axios Indianapolis as part of a reporting partnership about youth gun violence in Indianapolis.

As teenager Oswin Ortiz Jr. lay shot outside his home in 2019, his father approached him and asked who had shot him.

“All he could say was ‘Snapchat’ and pointed to his phone,” police wrote in a probable cause affidavit for the arrest of Joshua Grow.

After Ortiz’s death, police officers went through his and Grow’s Snapchat accounts. There, they found videos Ortiz took of THC he was trying to sell, according to the affidavit. And hours before Ortiz’s death, Grow was trying to find someone he could rob.

“Where a lick,” read a message from Grow’s Snapchat account to another acquaintance, using slang for a robbery target. “I need money.” Grow, who was 18 at the time, eventually pleaded guilty to a charge in connection with Ortiz’s shooting and was sentenced to several decades in prison.

Since 2018, over one-third of the gun homicides involving Indianapolis youth for which prosecutors have brought murder charges have featured social media in some form, according to a Chalkbeat and Axios analysis of 72 probable-cause affidavits. Teenagers use Facebook to set up drug deals that turn into robberies gone wrong. Trash talking that starts on Snapchat ends in gunfire. Police search Instagram messages and videos for clues.

Social media’s complex role in the city’s youth gun homicides makes for a daunting obstacle in curbing youth violence. Already, 21 people ages 19 and under have been killed by gunfire in 2025, more than all of last year. Since 2020, nearly 200 people in that age range have been killed by gunfire.

The algorithm of platforms like Instagram can feed vulnerable youth a fake reality in which violence is the norm, students and experts say. It can also amplify pre-existing drama between students before an audience of their peers both during and outside of school hours. And it can make communication between teenagers — whether to meet up to trade a gun or buy marijuana — instantaneous and discreet.

Each of these pieces contributes to a youth violence problem that’s difficult to solve, but not impossible, researchers say. And calls for the city to do more have reached a fever pitch after a mass shooting involving at least four teens in the heart of downtown during the Fourth of July weekend.

Paul Boxer, a professor of psychology at Rutgers and author of “The Future of Youth Violence Prevention: A Mixtape for Practice, Policy, and Research,” said there are effective strategies to combat youth violence that social media is exacerbating, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. But they often come with a fairly significant upfront investment that communities don’t always want to make — despite cost effectiveness studies that show a positive return.

“We can prevent youth violence,” Boxer said. “We can prevent gun violence. Where there’s a will there’s a way.”

Social media aids meetups, makes private fights public

Ania Raines remembers her brother, 16-year-old Xavier Weir, arguing with people over Instagram live in the months leading up to his death in 2019.

Isaiha Funez, one of the two people charged with his murder, told police that Weir posted a $1,200 bounty on his head on Snapchat weeks before.

Weir, in turn, was being accused of giving information to authorities about car thefts in Carmel, Raines said.

“‘He’s calling you a snitch,’” one girl said to Weir in a video, according to Raines. He sent emojis of laughing faces back in response.

All that time, Weir’s peers at Scecina Memorial High School watched the drama from their phone screens. After his death that April, a classmate showed Weir’s mother, Michelle Raines, the arguments that unfolded over social media — which the classmate had recorded. (Funez eventually pleaded guilty to a lesser charge.)

Since 2018, many of the gun homicides involving school-aged children that have reached the Marion County prosecutor’s office have involved social media in some form.

In at least 25 out of 72 of those homicides, police documented the use of Instagram, Snapchat, Discord, or Facebook in the moments leading up to or after the homicide, according to a Chalkbeat Indiana and Axios Indianapolis analysis of affidavits for those arrested for the deaths.

The analysis examined cases filed from 2018 through late January 2025, and includes all cases in which a defendant or a victim of gun homicides were ages 6 to 18. (Not all defendants arrested for these homicides were convicted of murder — some had their cases dropped, for example, while others pleaded guilty to a lesser charge.)

Data: Marion County Prosecutor’s Office, Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department, and probable cause affidavits.

Note: Not all defendants were found guilty as charges may have changed or cases may still be pending.

Chart: Kavya Beheraj/Axios

To teenagers, social media is a form of both entertainment and communication, students told Chalkbeat. Instagram trends can flood a school community. One account might be dedicated to publicizing school fights. Another account might post photos of students asleep in class.

Teens use social media apps in place of a classmate’s direct phone number, which can feel too personal. But that also means that communication between students is highly publicized.

Vague notes left on Instagram stories might be a “sneak diss” — an insult that does not directly name the target. Students fight through posts on their Instagram stories by screenshotting their aggressor’s post and writing their reply over it so that everyone can see.

“It’s one thing for someone to be rude to you,” said Noa Kaufman-Nichols, a recent graduate of Shortridge High School who was active in the school’s Key Club and student government. “But for someone to be rude to you in front of hundreds of people and possibly more if you have a public account, I think that adds a level of anger that [wasn’t] there before.”

The Chalkbeat and Axios analysis found that students also used social media often to meet in person and buy or trade guns or marijuana.

Hours before his fatal shooting in 2019, Weir advertised THC cartridges and marijuana for sale on Snapchat, one witness told police, according to the affidavit for Funez’s arrest. (Raines said that a detective later told her the cartridges contained nicotine, not THC). After Ortiz Jr. was shot the same year at age 17, police also found videos of THC he wanted to sell in his Snapchat account, according to an affidavit.

After Weir sold cartridges to girls at a westside gas station, a car followed him to a residential area in Beech Grove, where Weir was fatally shot.

Even after his death, Weir’s younger sister, Ania, faced bullying online, Raines said. One student at her private school sent a screenshot of Weir’s tombstone to her, asking her how her brother was.

“I told them, ‘This has got to stop, she’s going to end up retaliating,’” Raines recalled telling school officials before she pulled her from the school. “It’s not going to be good.”

Social media presents alternate reality to teens

Hours before his death in October 2021,17-year-old Abdulla Mubarak posted two videos to his Snapchat, according to police records. He was standing in a field, talking and laughing with 22-year-old Michael James, who is recorded shooting a handgun with a switch on it and emptying the gun’s magazine. Their bodies — along with the body of 18-year-old Joseph Thomas — were later found in the same field.

Social media can present an echo chamber for teens — one in which having guns, money, and marijuana is normalized, students and experts said.

“It turns into something you see every day, basically. It influences you to be like these people,” said Ariyah Mitchell, a recent Southport High School graduate who previously served on the Mayor’s Youth Leadership Council.

Social media algorithms can also preference controversial, emotional, and violent content to drive activity and engagement, Boxer said.

“It’s making them believe the world is a violent place,” Boxer said, “and suspect guns are a good way to solve problems.”

These kinds of posts and references on social media can help police make an arrest.

In the early morning hours of Jan. 4, 2020, a Snapchat user police believed to be Treshawn Davidson, 17, was looking for 15-year-old Peter Lambermont.

“He took my gun I need u to find him,” lilbandz1219 said to another user, according to an affidavit filed in Davidson’s arrest. Davidson later pleaded guilty to theft of a firearm and assisting a criminal, charges connected with Lambermont’s death.

Later that afternoon, Snapchat messages show that Lambermont met with Treshawn and 18-year-old Jakeb Wells, who was later found guilty of Lambermont’s murder. After Lambermont was found dead on the city’s east side, Wells posted a video of himself singing on Snapchat.

“That little kid got murk’d, I had to put him on a shirt,” Wells sang, referencing slang for murder, according to the affidavit. “I shot his body, made him twerk.”

Indiana seeks solutions in and out of school

User guidelines for several social media companies technically prohibit content containing violence or threats. To avoid spreading harmful content, Snapchat moderates content in Spotlight and Discover feeds before it is recommended for distribution to a larger audience, according to Snap, the company that operates Snapchat.

Meta, which operates Instagram and Facebook, says that it hides certain content from teenagers, including offers from legitimate businesses to sell firearms.

But those policies alone can’t fix the problem.

Government officials have tried both in-school and out-of-school solutions to limit screen time or reduce the potential for youth violence.

Northwest Middle School Principal Nichole Morrow-Weaver told Chalkbeat last November that Indiana’s cell phone ban in schools, which took effect last year, had a positive effect.

“A lot of the issues that we have stem from social media outside of school,” Morrow-Weaver said. “Without having the cell phones in schools this year, we’ve seen a big decrease in that.”

Yet other potentially useful in-school approaches aren’t getting the same support from policymakers.

Social-emotional learning can be effective in improving student well-being and reducing violence, research has shown. But Republican lawmakers removed teacher training requirements related to social-emotional learning, cultural competency and restorative justice this past legislative session as part of a larger school deregulation effort.

“Teachers should focus on academic rigor, math, science, reading, and writing, technical skills, instead of this emotional regulation, empathy, and et cetera,” said Sen. Gary Byrne, a Republican.

Studies conducted in school settings have also found that cognitive behavioral therapy-based anger management interventions are effective. But Indiana had just one counselor for every 351 students last school year, higher than the recommended ratio of 1-to-250.

Ratios for other school-based mental health care providers are even worse, with 2,700 students per school psychologist and 1,829 students per social worker, according to Indiana University.

Outside of school, Indianapolis officials recently implemented a stricter curfew for youth — but even city leaders disagree on the effectiveness of such policies.

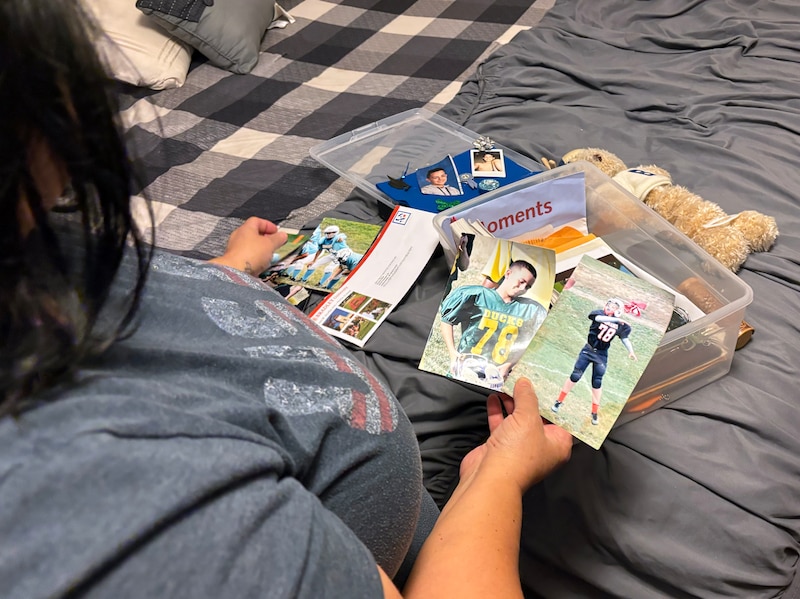

Weir’s bedroom is filled with childhood mementos — certificates of accomplishment from the private Catholic school he attended, a collection of Nike shoes stacked in boxes, and photos of him on the school basketball and football team.

His mother leaves it all packed up in remembrance of the life he lived. Her son played football and was recruited by Xavier University before his death. Last month, he would have turned 23.

Growing up, Raines said, she was outside playing with friends. Now, kids are texting each other from neighboring rooms.

“I wish we could just not have a phone,” she said.

Read the Axios Indianapolis story here.

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Lawrence Township schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.

Arika Herron is a reporter for Axios Indianapolis. You can reach her atArika.Herron@axios.com.