I recently saw photos of special education teachers making protective face shields out of Velcro strips and laminate sheets.

The photos came from a teacher who works at a very expensive private school in Manhattan for students with autism spectrum disorder. But it was the kind of creativity all teachers of students with autism are accustomed to. Their classrooms often don’t have all of the resources or the staff they need, but teams of educators, therapists, and specialists together make it work for students.

But in the time of COVID-19, I’m worried that educators’ creativity won’t equal safety, despite their best efforts. These students and teachers are in a uniquely problematic spot, and no one appears to have a proper plan.

The physicality of this job is the same everywhere. I’ve worked in private schools specializing in students on the autism spectrum, and over the last six years I’ve spent extensive time conducting observations in New York City’s public District 75 schools, serving students with significant disabilities, and charter schools for students on the autism spectrum. In any of these schools, the idea of social distancing from a student with level 2 or 3 autism, meaning they have moderate to severe impairments, is incomprehensible.

Most students require some assistance at mealtime. Many students have individualized sensory protocols that involve teachers using a special comb to brush students’ arms, legs, and backs. Some students are learning how to independently complete bathroom routines.

Speech pathologists help strengthen mouths and tongues by using specialized tools that must be inserted into a student’s mouth. Some students wear a chewy necklace, which is a nontoxic ring that gives students a way to mouth and chew appropriately. It is an item that needs to be washed throughout the day, and when students are frustrated, it sometimes gets hurled across classrooms, sending saliva flying.

Not only do our students’ daily needs make social distance impossible, so do many of their wants. It’s a misunderstanding that students with autism don’t crave human touch. Students with autism may request hugs, tickles, and squeezes throughout the day.

The thought of creating a social story — a narrative meant to explain a particular situation — titled “No more hugs or tickles because of COVID” seems too much to bear. Most of these routines can’t realistically change, anyway.

The reality is that students with autism and others with highly specialized requirements need in-person school more than other student populations, but the actual work puts both teachers and the students at risk for transmitting COVID-19. The adults who work with these students can’t rely on the kind of social distancing other educators can.

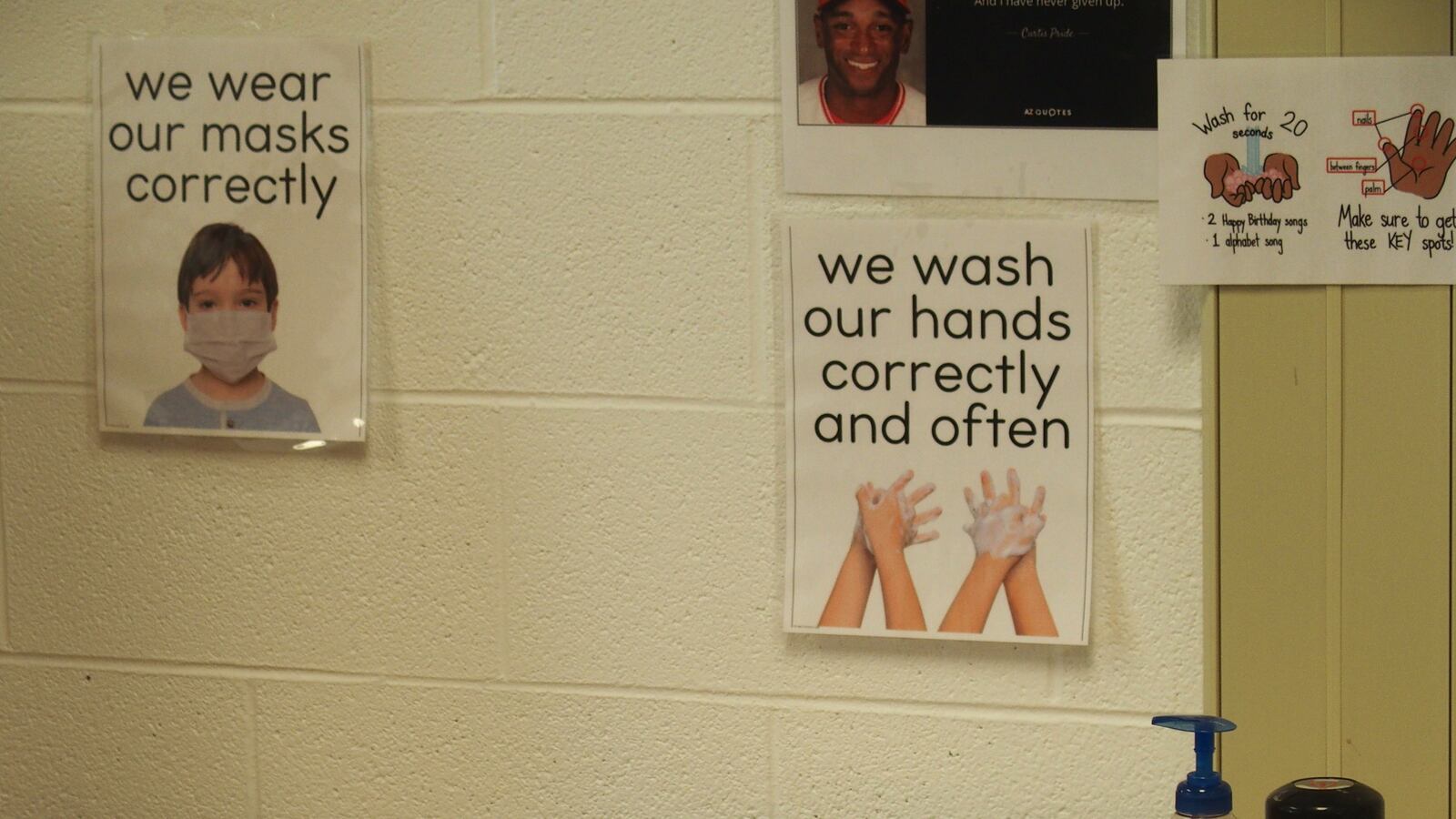

That means educators of students with autism need more comprehensive planning and guarantees of proper personal protective equipment. Hand sanitizer with the recommended percentage of alcohol should be readily available. Air filters should be spread throughout the school as recommended. Coronavirus testing should be frequent and mandated, and educators should be provided with not just masks but also face shields and goggles.

At the private school in Manhattan where teachers are making face shields, teachers feel trapped by the lack of personal protective equipment, hot or even warm water, and working thermometers. I hope New York City’s public schools will do more.

Without special attention, the students with the highest needs, and the teachers who work with them, will be left in an unsafe and unethical spot.

Samantha Mann writes primarily nonfiction essays exploring LGBTQ life, mental health, and feminism. She has published essays in Elle, Bustle, Bust, and various other publications. Her debut essay collection, “Putting Out: Essays on Otherness,” was published in March 2016 by Read Furiously. Find more of Samantha’s work here.