A seventh-grade girl in black skinny jeans and a black cardigan casually strolled into the gymnasium before fifth period at Falcon Bluffs Middle School in Littleton. She crossed toward a box of bright orange pedometers sitting on the floor, stooped to pick one up and immediately broke into a run as she headed to the locker room to change. She wasn’t late for class.

Neither were the boys who burst through the gym doors and sprinted to the pedometer box or the girls who speed-walked to the locker room.

Strange as it sounds, the students were all rushing to rack up Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity minutes in P.E. class. Commonly known as MVPA, the student keep track of their minutes using the pedometers, which they clip to the waistband of their green gym shorts.

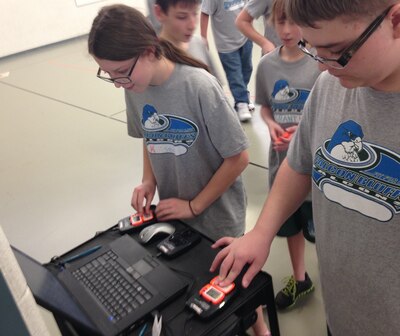

In addition to arriving early for P.E at Falcon Bluffs, students hopped up and down or skipped in circles while waiting for class to begin. They jogged in place while standing in line to bat during the day’s indoor baseball game. Some kept bouncing at the end of class as they waited in line to insert their pedometers into docking stations that would record their MVPA numbers in a computer database.

The students’ motivation to move stems from the school’s new approach to physical activity, both during P.E. and a before-school fitness program. It’s no longer just a means of achieving physical fitness, but also mental fitness, with the pedometers serving as a source of instant feedback and a tool for long-term tracking. The new approach, which began at Falcon Bluffs and four other Jeffco schools last year, is based on the work of Harvard psychiatry professor John Ratey, who wrote, “Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain.”

While many educators instinctively sense that exercise helps kids in the classroom, the reasons are often articulated with vague explanations like “it burns off energy” or “it gets the wiggles out.” Ratey details the science behind the intuition, describing how exercise affects neurotransmitters and brain infrastructure to facilitate learning.

“He calls exercise ‘Miracle-Gro for the brain,’” said Emily O’Winter, Jeffco’s healthy schools coordinator. “It is so compelling. It’s so motivating to exercise for your brain.”

In the education realm, there may be no better example of the brain-fitness connection than Naperville School District 203, a high-achieving district near Chicago that pioneered many of the physical education practices that Ratey recommends. In “Spark,” Ratey lauds the district’s student body as “perhaps the fittest in the nation” and talks about their world-class performance on the international TIMSS test.

The idea of leveraging exercise for academic success obviously intrigues principals and teachers, but it also seems to resonate with students. During a recent P.E. class, seventh-grader Brody Hall jogged in place as he explained to a visitor why he comes to the before-school “Spark” most days. “I wanted to come … in the morning and get my brain going for the day so I’d be able to learn better.”

His first class is language arts and he said his mind wanders less when he attends Spark first.

“I think it’s just like I’m more focused and ready to learn and more awake.”

This spring, the district plans to expand its Spark-inspired approach to seven additional schools with the help of a $200,000 “Thriving Schools” grant from Kaiser Permanente. Next fall, the funds will allow up to 15 additional schools to come on board.

While Jeffco is hardly the only Colorado district attempting to increase students’ physical activity, its approach appears unique. The use of pedometers and the careful tracking of MVPA is uncommon, said Jamie Hurley, a professional development consultant for RMC Health who has worked with many districts on physical activity initiatives. More often, he said, schools try to increase opportunities for physical activity throughout the school day, perhaps in the form of added recess or classroom “brain breaks.”

The hallmarks of Spark

Jeffco’s brand of Spark, which is not to be confused with two unrelated programs –the SPARK physical activity curriculum and SPARK After-School Academy—aims to provide daily or near-daily chances for physical activity at school with the goal of measuring and boosting students’ MVPA. Ideally, Spark takes place just before core academic classes though scheduling logistics don’t always allow that.

Ryan West, the principal at Falcon Bluffs, launched the school’s first iteration of Spark in the fall of 2012 after a central administrator gave him and four other principals a copy of Ratey’s book.

“I had no idea that this was out there,” said West. “I knew the anecdotal stuff about the importance of athletics, but I didn’t have the research.”

West, with the help of counselor Rob Longbrake, soon launched a Spark elective class, selecting 16 students, mostly boys, who were reading below grade level. Each day, Longbrake led the students in a physical activity session in the former staff lounge, which had been equipped with stationary bikes, workout videos and circuit training equipment. The students tracked their MVPA using heart rate monitors strapped around their chests. Right after Spark, the students went to their remedial reading class.

Longbrake quickly discovered the kids didn’t enjoy spinning and weren’t as driven as he’d expected.

“So I finally just said, ‘OK guys, what do you want to do to get moving here?’” he said. “So we ended up…doing anything we could to move. We played a lot of ultimate football outside.”

Meanwhile, the students made huge academic gains in reading.

“Their TCAP scores went through the roof,” said Longbrake. “It was pretty cool.”

West said all the students had scored “unsatisfactory” on the 2012 TCAP reading test. On the 2013 test, all but two scored “proficient” or “partially proficient” and more than half showed higher-than-average growth rates. In some cases, students went from reading at a first- or second-grade level to a fifth-, sixth- or seventh-grade level, he said.

O’Winter said the preliminary findings, which were similar at the other schools, are encouraging but can’t be indisputably attributed to the Spark programs.

“The thing is we’re not a research institute,” she said. “With this data we hope to show success, but we can’t prove anything without a randomized clinical trial.”

Taking it schoolwide

While the first-year data may not rise to the level of a scientific study, Falcon Bluffs administrators found it convincing enough to expand the Spark philosophy to all P.E. classes this year, and launch a 7 a.m. Spark fitness session four mornings a week.

The biggest change, aside from a wider swath of participants, was the switch from heart rate monitors to the more user-friendly pedometers, which use an algorithm based on step counts to calculate MVPA. While the heart monitors are probably a bit more accurate, the straps got sweat soaked after one or two class periods and the associated software didn’t always work, said P.E. teacher Allyn Atadero.

While the pedometers provide instant feedback on exercise intensity, students seem to glean at least as much inspiration from the many lists Atadero posts on the gym bulletin board. First, he created the 10-Minute Club, posting the name of every student who achieved at least that amount of MVPA during his 44-minute class. Initially, his hope was that 70 percent of students would reach that threshold.

“I thought I was shooting high,” he laughed.

Turns out, he was shooting too low. Pretty soon, Atadero added a 20-Minute Club, a 30-Minute Club, even a 40-Minute Club. He also created a Top 10 Boys list and Top 10 Girls list for every class, a Top 10 All-Time list and class vs. class competitions.

Perhaps most surprising is the 50-Minute Club, which was added a few weeks ago after one boy somehow spent every minute of P.E. plus most of two passing times in the MVPA zone.

“I can’t think of any student I have that has not bought into it, every single kid,” said Atadero.

While there are certainly a share of lean, athletic students who make the high-minute clubs, Atadero said he’s seen major improvements even by students who don’t typically embrace fitness. He described one girl in morning Spark, who started out with only two to three minutes of MVPA during the 40-minute session. Now, just by picking up her walking pace, she routinely breaks 20 minutes.

Atadero also said Spark has changed the way he teaches some of his P.E. units. For example, to incorporate more movement into baseball, he now requires students to sprint across the gym and touch the bleachers after every three outs. He also grades on effort, not athletic ability, awarding the top score of four to every student who achieves at least 10 minutes of MVPA.

“I have that tool now where I can monitor 100 percent of my students,” he said.

Lack of policies, funding

While West, Atadero and others involved in the Spark experiment at Falcon Bluffs are enthusiastic about the program, it’s not without weaknesses. For one, physical education is not required at the middle school level in Jeffco, so about 15 percent of Falcon Bluffs students don’t take it at all.

Those who do, take it daily for one trimester, or about 12 weeks. That means any benefits, whether physical or academic, are temporary, except for the 30-40 students who voluntarily attend before-school Spark.

What about the possibility of offering daily P.E. to students all year?

“I would absolutely love to do that. That would be a dream of mine,” said West, a former high school football coach. “The reality is I have 650 kids in this building and Allyn is my only P.E teacher.”

O’Winter said that problem exists across the district. Still, she believes excitement about Spark is growing and feels it provides a better solution for struggling students than loading them up with extra academics.

“Why isn’t this the most obvious thing?” she said. “This is how our brains are built.”