A heavy routine has taken shape at some schools across the country.

A tragedy grips the nation — often the killing of an unarmed Black man by police, but sometimes it’s a woman or a teenager — and school leaders bring their students together to learn, to process, to grieve.

The conversations Wednesday, a day after a jury found former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin guilty in the death of George Floyd, were in some ways unique. The verdict brought a measure of relief, a semblance of accountability in a death that served as a catalyst for a massive protest movement.

But in other ways, the town halls and conversations and safe spaces held in classrooms and over Zoom were similarly somber. Because George Floyd was still dead. Because another teenager was killed Tuesday.

In Brooklyn, a school read a remembrance poem for Americans killed by police. In Newark, a school board member reflected on the textbooks her community needs. And in St. Louis, a class of sixth graders talked about their own city’s history of police violence.

One Brooklyn high school’s sad ritual

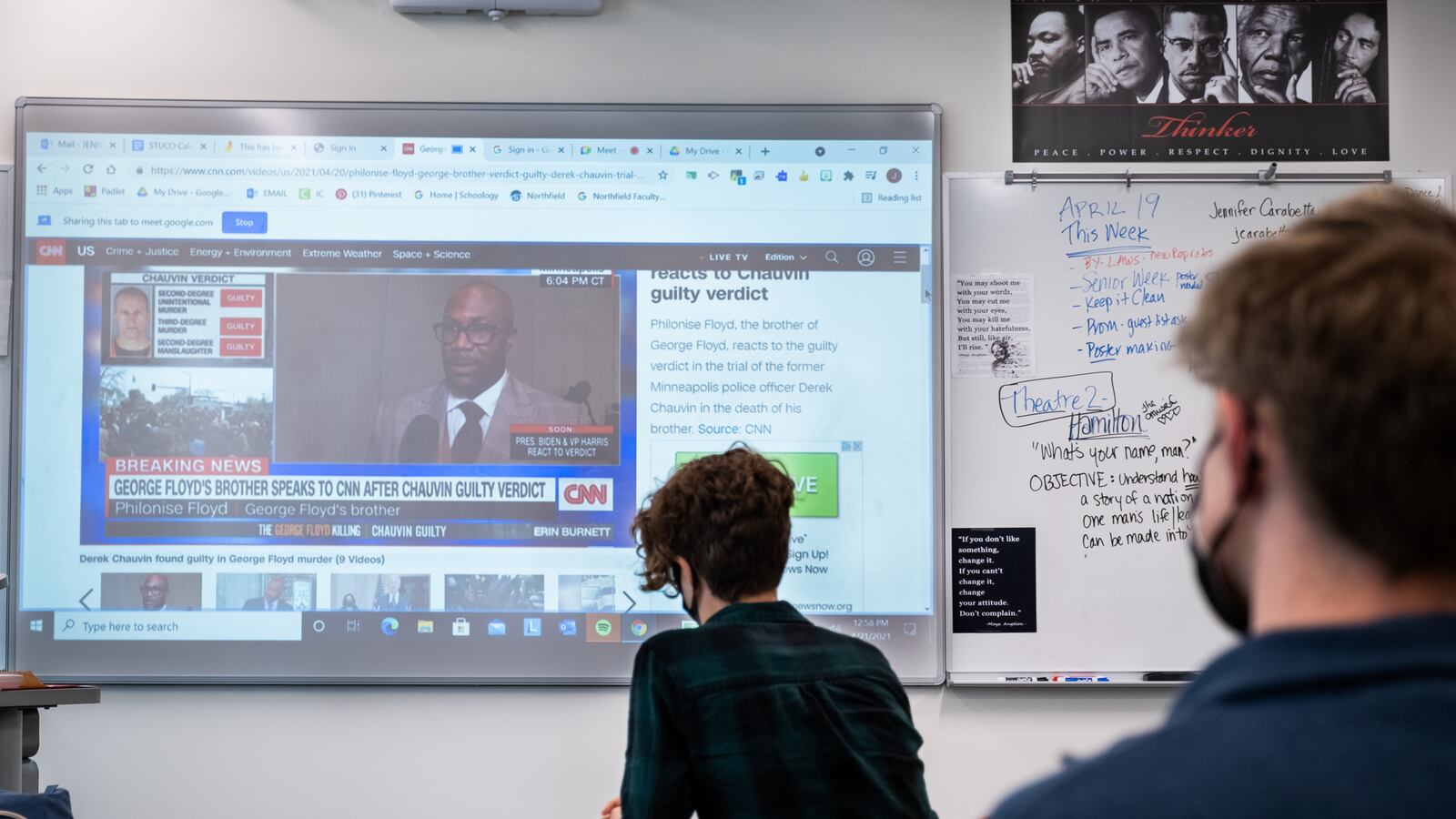

Principal Robert Michelin opened a virtual town hall Wednesday for his Brooklyn high school by summarizing the historic murder verdict.

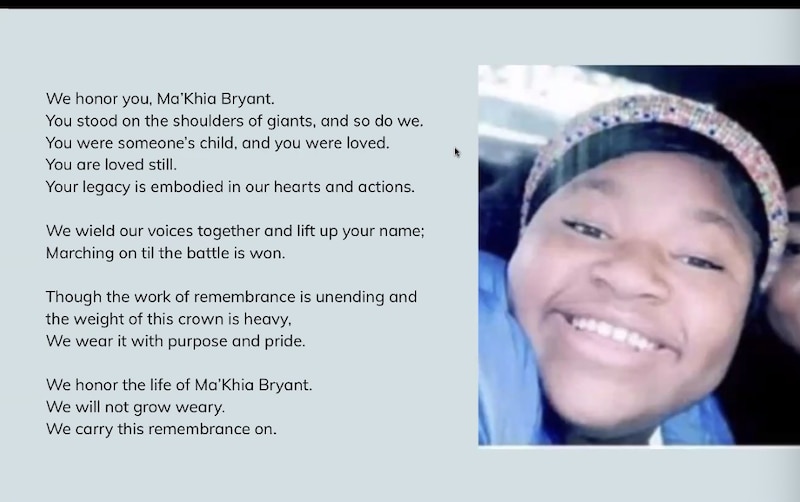

Moments later, Michelin informed students that a Columbus police officer had fatally shot teenager Ma’Khia Bryant about a half hour before the Chauvin verdict. The shared screen changed to a “remembrance” poem that the school created for people killed by police, next to a picture of Ma’Khia. Many of the 70-plus participants on the Zoom turned on their microphones to read the poem aloud – a ritual they’d performed about a dozen times in the past year. One student wrote in the Zoom chat, “UGHHH I HATE DOING THIS.”

“I know doing this is hard and it’s painful, and it’s hard for the wounds to heal when we reopen them like this,” Michelin said in response to the student’s comment. “But if we allow ourselves the space to forget — as we have for a long time, right? — it makes it harder to really get the progress that we need to move forward, in the ways we must as a society.”

When Floyd was killed last May, the school, Gotham Professional Arts Academy, held a similar town hall. The next month, the school held a “day of action,” where students presented activism-focused art projects.

Over the past year, the school has tweaked its curriculum to lean toward activism and examine racial disparities in various subjects, Michelin said. For example, the school’s freshmen have been studying why the coronavirus pandemic has more severely affected Black and Hispanic communities.

This ongoing focus on racial justice meant that when the Chauvin verdict was announced, Michelin and some teachers were well positioned to plan activities for the next day.

During the 90-minute town hall, some students shared their frustrations with the criminal justice system and policing. One student, Soby, asked why police officers carry guns at all times, believing weapons may be necessary for a drug bust but perhaps not a call of domestic abuse. The same student, who believed the evidence for murder was clear, questioned why the jury needed more than a day to deliver the verdict and wondered why murder charges come in different degrees.

Some students said they were upset about people celebrating the verdict, since it won’t bring Floyd back to his family. “In reality that’s a whole life, a whole person gone,” a student named Hannah said. “No matter what the government decides to do, he’s still dead.”

In the chat, a different student wondered why protestors weren’t more excited about the outcome, saying “it’s dumb” to be unhappy after getting justice. A staffer responded that people are happy the “system held an officer accountable,” but justice would mean “people of color would be seen as equal under the law.”

Michelin said he or other staff members try to follow up with students to understand their perspectives. In the case of the student who questioned protestors’ unhappiness, staff would offer to have a conversation to better understand his view, but he doesn’t have to take them up on it, Michelin said.

“My job is not to hope he thinks a certain way,” Michelin said. “My job is to hope he thinks perpetually.”

— Reema Amin

An ongoing reminder

Like so many Americans — and Black Americans, in particular — Asia Norton felt a wave of conflicting emotions Tuesday. The guilty verdict brought relief, but the occasion was tinged with sorrow and anger.

“Yes, justice is being served,” she said. “But why does it have to be this way? Why are we celebrating someone being convicted of murdering a Black man, a Black father, a Black son?”

As a former teacher and current school board member in Newark, N.J., Norton was considering how schools could address the trial and the issues it raised, including systemic racism and police violence against Black people.

For one, textbooks and lessons should reflect the lived experiences of students of color in America and provide an unvarnished depiction of American history — including its legacy of racism, she said. Also, students need to feel safe discussing those topics in class, and teachers need training on how to lead such conversations, she added.

If Tuesday’s verdict reminded some Americans of the prejudice and racial violence that remain common in this country, it also underscored how other Americans never had the privilege of forgetting.

“I’m an African American woman raising her Black son in the city of Newark, which is predominantly Black and Brown,” Norton said. “So I’ve been thinking about this ever since the day I was born.”

— Patrick Wall

What might have been

Just before 8 a.m., Monica Reed sat atop a desk in the middle of her classroom, ready to lead what she hoped would feel like a family meeting with the 11 sixth-graders before her.

Reed teaches African American culture at KIPP Inspire Academy, a middle school in St. Louis, and she often talks with her students about current events and the history of racism in America. She knew her students, half of whom watched the Chauvin verdict, would be ready to discuss it.

She began by asking how they would have felt if Chauvin had been found not guilty.

“I would honestly feel mad because he did all that and then his family didn’t get justice,” one student shared.

“I would have felt …” another student began. “I would have felt messed up. Because not only are you killing a Black man, and he’s saying he can’t breathe, but still, you got it on video.”

Reed used the student’s point to talk about how cell phone recordings and social media have changed how police are prosecuted. And she told students they could become the next generation of lawmakers who could make changes to how police are held accountable, too.

“What I want you to learn how to do is grow up and not be afraid to say and do what is right,” she told them.

To bring home the magnitude of the guilty verdict, Reed recalled what it was like in their city when Darren Wilson, the police officer who shot and killed Michael Brown in 2014, wasn’t charged with any crimes. She thought it was important to draw on the knowledge her students had about Brown, who faced some of the same challenges as them.

“St. Louis erupted,” Reed told her students, many of whom receive special education support. One nudged her to explain what the word meant. “It means we exploded.”

Then Reed relayed the memory she had of leaving a science field trip early with her students on the day the announcement was made back in 2014, in anticipation of the protests that would break out when no charges were filed. The police station two blocks from their school was set on fire.

“St. Louis will never be the same,” she said. Had Chauvin not been found guilty, “this would have been the same thing.”

— Kalyn Belsha

‘I don’t feel satisfied’

Students in Jennifer Carabetta’s student council class at Denver’s Northfield High School helped organize one of the biggest Black Lives Matter marches in the city last summer. On Wednesday, some of those same students discussed the verdict.

Carabetta started by having the students, some of whom were in person and others of whom were online, type their thoughts on virtual sticky notes. She read some responses out loud.

“This case will be a pivotal point in the elimination of systemic racism in the United States,” one student wrote. Others saw it differently, saying the case was important but the issues underlying it — racism and police brutality — are still rampant.

“Honestly, right now, I don’t feel satisfied,” another student wrote.

“He was convicted, so we count this one as a victory,” yet another student wrote. “But all of the other ones … got away and were not held accountable. Yesterday was just the beginning.”

After Floyd’s death last year, the Denver school board voted to end the district’s contract with Denver police. School resource officers are being phased out districtwide, and Northfield is set to lose its school resource officer at the end of this school year.

Some students in Carabetta’s class argued it was unfair to characterize all police officers as bad. Senior Gabriel Watkins said he wasn’t allowed to play with Nerf guns as a child for fear an officer would mistake it for a real weapon. But he said having police work in schools is a good thing because it improves relationships between police and young people.

However, sophomore Gabriela Kobak said that characterization, the stigma that all police are dangerous, is born of real fear. “People have the right to be scared,” she said.

— Melanie Asmar

Nine and a half minutes of silence

Shortly before noon at Denver’s South High School, a group of students filed out of the building holding large banners that read “Black Lives Matter” and “How Many More?” Under gray skies, in a damp chill, they stood in silence for 9 minutes and 29 seconds, the amount of time that Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck.

Ninth grader Graça Jovelino bowed her head as she held a drawing she had made of Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery.

“These things that are happening are not normal,” she said in Portuguese. “Racism is a sickness of some white people. We’re all children of God, and we should love each other in spite of everything. Inside, we’re equal. We shouldn’t be mistreated.”

Charlotte Anderson, student body co-president at South, said she started crying when she heard the verdict. A high school senior, Anderson found walking out with her classmates, as students at South have done many times in response to injustice, a comforting act of normalcy in what has been a strange school year.

At the same time, standing outside in the cold weather drove home just how much Floyd suffered.

“My hands were numb, but it was really important for everyone to feel the weight of just what a long time that is,” she said. “It felt like forever.”

Madison Baldwin, a member of the Student Senate at South, said students there planned to take some kind of action whichever way the verdict turned out. South is a diverse school serving many immigrant students. Baldwin, like most of the students who walked out of school Wednesday, is white. She said it is important for white students to speak up and use their privilege to work for change.

“It’s important to recognize that this is an amazing victory, but this is just a small fraction of the accountability that needs to be served,” she said. “This isn’t justice.”

— Erica Meltzer