As students across the country wrestled with pandemic stress last winter, sophomore Nathaniel Martinez logged on to a virtual retreat. Forty mostly Black and Latino teens in Chicago were getting a crash course on gauging how their peers were coping.

They also opened up about pressures they faced amid the COVID-19 outbreak and an uptick in gun violence, from depression to disengagement from school.

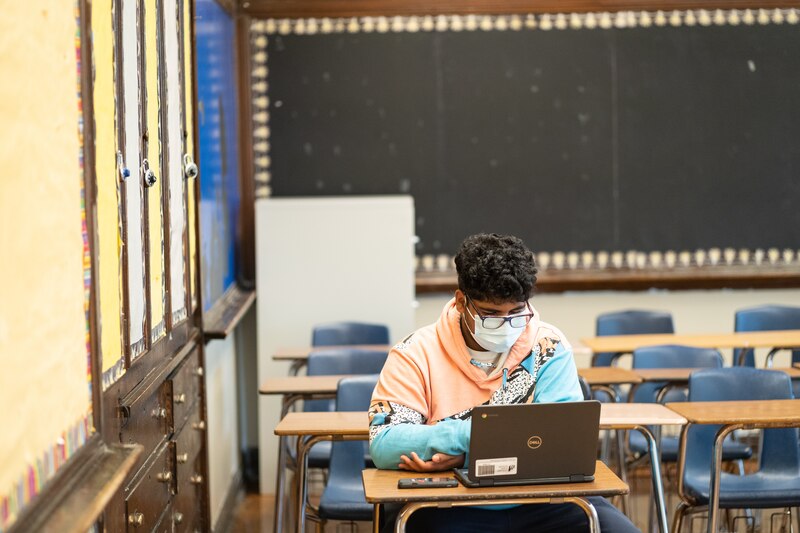

Nathaniel spoke about struggling to focus in virtual classes as he grappled with isolation and insomnia.

The project offered Nathaniel a support group of sorts as he returned to full-time in-person learning this fall, short on credits but bent on regaining his footing. It also gave him an active role in reimagining how schools can better help teens of color.

School systems have long vowed to shrink the disparities in graduation, college enrollment, and other outcomes that leave Black and Latino boys consistently behind girls of color. The pandemic’s disruption further widened such gaps. In Chicago and nationally, data show a steeper drop in attendance and a more marked increase in failing grades for male Black and Latino students.

The country’s reckoning over race has brought a greater sense of urgency to the search for solutions, and districts are flush with billions of federal pandemic relief dollars. But so far, most efforts to rethink learning for male students of color seem to be relatively small-scale, often driven by nonprofits rather than schools and colleges, say experts such as Roderick L. Carey, professor at the University of Delaware who studies the educational experiences of Black and Latino boys and young men.

“I’m not seeing many concrete steps to reimagine schooling in the wake of what we have experienced with racial unrest and COVID-19,” Carey said. “Folks seem to be just trying to get back to business as usual.”

Still, advocates are encouraged by initiatives that show promise, including new programs to steer more Black and Latino males into teaching, and efforts such as the project Nathaniel joined that give students more agency in helping find solutions. The project, a partnership between Chicago’s Lurie Children’s Hospital and nonprofit Communities United, was just named among 10 finalists in the Kellogg Foundation’s international Racial Equity 2030 Challenge, which comes with a $1 million planning grant and a shot at winning up to $20 million.

Pedro Martinez, the former San Antonio superintendent who took over as Chicago schools chief at the end of September, says addressing the pandemic’s fallout for Black and Latino boys will be a priority.

“We wanted to shift the gaze of research away from the trauma and the pathologies and toward solutions,” said Dr. Claudio Rivera, a clinical psychologist at Lurie Children’s who is part of the research project. “These young men are our mental health expert partners and co-researchers. That to me is empowering and hopeful.”

Boys of color as agents of change

The idea behind the Lurie-Communities United initiative: Since Chicago’s South and West Side neighborhoods had seen the heaviest health and economic toll from the pandemic, local youth were in the best position to assess what teens like them need to bounce back.

That original group has since shrunk to a core group of about a dozen who continue to meet. Those boys have found a sense of belonging and license to be vulnerable with each other. Some students refer to the group as a “brotherhood” and “family,” Rivera said. Others have reached out to him and other facilitators for advice and support.

The evening after Chicago Police released a video of an officer fatally shooting 13-year-old Adam Toledo last spring, the teens conveyed their shock and grief at seeing the killing of a student who shared a ZIP code and life experiences with some of them.

They spoke about encounters with law enforcement they had in their schools and neighborhoods. One member of the group told a Lurie facilitator that the conversation had overwhelmed him and he needed to step away from the screen — which Rivera saw as evidence of the trust and camaraderie the project had built.

“The most important thing you can give young men of color is an outlet,” said Nathaniel, who identifies as Afro-Latino. “They don’t really get an outlet that’s healthy.”

The pandemic and the national racial reckoning have fired up educators and advocates focused on male academic achievement, said Edward Smith, a program officer at the Michigan-based Kresge Foundation. But amid this unprecedented confluence of crises, he and other advocates are losing patience with incremental efforts to break with harmful practices, from disproportionate school discipline to curriculums that don’t reflect student experiences.

Instead, there is an appetite for a more comprehensive, radical reimagining — especially efforts to engage boys and men of color as partners and agents of change.

Smith points to a New Orleans program Kresge supports called Brothers Empowered to Teach, which steers Black male students to careers in education, where boys of color face a shortage of role models.

By 2020, the program, which has come to partner with 20 school districts and college and university campuses, had graduated about 50 participants. About 75% started teaching or went into teacher training programs such as Teach for America. About 60% remained in education jobs two years after graduating.

Tragedies close to home

This fall, Chicago Public Schools and the nonprofit Thrive Chicago — a local partner of former President Barack Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative — are launching a similar pilot project at five district high schools, where 100 male Black and Latino students will take a new, year-long “Introduction to Urban Education” course.

There, they will explore the idea of teaching as a form of activism for young men of color and get mentoring and support as they eventually continue to education programs on local college campuses.

Sonya Anderson, Thrive’s president, says the pandemic strengthened her belief in the importance of programs geared toward supporting male Black and Latino youth. Then came a personal tragedy. Earlier this summer, her 18-year-old stepson, Miles Thompson, was shot and killed in an apparent robbery while visiting his father in Austin, on the city’s West Side. Anderson’s 10-year-old son discovered his brother’s body in the yard the morning after the shooting.

For Anderson, the tragedy redoubled her sense of purpose. By speaking out about the loss of her stepson — a college-bound athlete from a well-to-do suburb — she wants to explode a false narrative that Chicago’s young gun violence victims are invariably troubled youth living in the city’s most troubled neighborhoods.

“‘Those people’ feel very different from us,” she said. “Now it’s not ‘those people over there.’ I have two Ivy League degrees and worked for Oprah, and my son died in the backyard because somebody shot him.”

She plans to be more vocal in pushing city and civic leaders to back investments in mentoring, social and emotional support, and job development. Those, she says, could reduce violence and disrupt a “pipeline of disconnection” that Chicago youth, especially boys and young men, face.

Thrive already partners with nonprofits in Roseland and Little Village in operating two Reconnection Hubs: one-stop shops for education, employment, and mental health support for “opportunity youth,” 16- to 24-year-olds who are not in school or working, a majority of whom are male. The Hubs, which have served 1,230 young people since 2018, have seen more demand amid the pandemic. Most recently, the nonprofit Phalanx Family Services, which hosts the Roseland Hub, steered 500 participants to a city of Chicago summer jobs programs.

“We can only create lasting system change when the Chicago Public Schools of the world are at the table,” Anderson said.

Giving students a say

Last spring, Al Raby High School on Chicago’s West Side set out to measure its students’ sense of belonging and connectedness to the campus amid the pandemic’s disruption.

The school, which serves a mostly Black and low-income student body, wanted to know what the boys were feeling: Did they think their teachers cared about them? Did they feel valued? Drawn by Al Raby’s popular football program, boys outnumber girls at the school about 2 to 1. But, a survey used by educators showed, their connection to the school is tenuous.

“Our boys did not feel their identities were recognized and did not feel as much a part of our classrooms as our girls,” said Michelle Harrell, the school’s principal.

With a grant from the Chicago Public Education Fund, the school launched an effort to re-engage freshman and sophomore boys who read below grade level. Al Raby will explore a conference model in which a teacher checks in with a small group of students each week, fostering all-important relationships.

The school will continue to host a mentoring program called Becoming a Man. Learning at home last year challenged boys of color, who can be more reluctant than girls to reach out for guidance and support. The program this fall will strengthen its focus on empowering young men to advocate for themselves, says Phillip Cusic of Youth Guidance, the nonprofit that runs it.

Al Raby also plans to strike up mentoring relationships between those freshmen and sophomores and its upperclassmen.

“We are really trying to elevate and be responsive to student voices this fall,” Harrell said. “If that means we have to scrap all the planning we did over the summer, so be it.”

In recent years, some districts across the country have touted new commitments to racial equity, but fewer have launched programs geared specifically toward Black and Latino boys.

A notable example is a program called Kingmakers of Oakland, which sprang out of Oakland Public Schools in California more than a decade ago and has since been embraced by eight districts in three states, including Seattle. The program cultivates male Black student leaders through mentoring and the study of Black history, and more.

In Chicago, the school district vowed in 2019 to prioritize Black and Latino boys in its push to raise achievement but, two years later, it still has not spelled out specific strategies.

The district, which was under interim leadership over the summer and intensely focused on reopening schools for full-time in-person learning at the time, declined an interview for this article. But last spring, Maurice Swinney, now Chicago’s interim chief education officer, pointed to an effort to connect students to jobs that do not derail their education and to a districtwide initiative to train educators to respond to students’ mental health needs.

District data shows a deeper plunge in attendance and a steeper increase in failing grades for Black and Latino boys last school year than for girls of color.

The district, which received almost $3 billion from three federal pandemic relief packages, is using a formula to push more funding to schools with higher student needs, where principals have some leeway on how to spend it. At the district level, the money will largely power more sweeping efforts such as the mental health training initiative rather than programs targeting specific student groups.

Educators have a powerful opportunity to connect with male students of color as they return to school campuses this fall, says Carey at the University of Delaware.

In the fall of 2019, Carey started The Black Boy Mattering Project, in which he and other researchers met regularly with a group of high school students to explore how they perceived their value and worth in school and society. Many told him that few of their teachers brought up the high-profile police killings of Black men and racial unrest following George Floyd’s murder — even as they regularly asked how students coped with the COVID outbreak.

The students felt a major part of their lived experience went unacknowledged.

This fall, Carey said, educators should tip to students’ experiences with this “dual pandemic” and use the crises in their lesson plans to stir discussion.

“The pandemic exacerbated feelings of nonbelonging and not-mattering; already tenuous relationships between schools and Black boys became more frayed,” said Carey. “We can use COVID as a miraculous opportunity to change schools for the better.”

This fall, Nathaniel’s group of young researchers is signing up participants for a mental health survey and research interviews in their neighborhoods. The results could inform trauma response training for Chicago’s educators.

In the meantime, Nathaniel started the school year at Roosevelt High School in Chicago’s Albany Park neighborhood as the district returned to full-time in-person learning. He had tried to make up several classes in summer school, but illness prevented him from finishing them.

What does he need from his school to bounce back?

Grace, for one. Too much homework can derail students like him who will be juggling regular school with evening courses to make up for classes they failed last year, he said.

And more of the social and emotional outreach that educators embraced during the pandemic.

“A simple ‘Hey, how’s your day going?’ from a teacher,” Nathaniel said, “makes a big difference.”