This is the first in a two-part project on school funding. Read the second piece — focusing on New York state’s disconnect between spending and test scores — here.

Deirdre Pilch has spent much of her career as an educator frustrated.

The superintendent of schools in Greeley, Colorado — a high-poverty district 50 miles north of Denver — has never felt she’s had the money to provide students the education they deserve.

Remarkably, it took a pandemic to change this.

After COVID first hit, experts predicted financial ruin for schools. But state budgets recovered quickly. Then, the federal government sent nearly $190 billion to schools — an unprecedented sum.

“That funding feels like I can actually now do some of the work I’ve needed to do, really my entire career in Colorado,” said Pilch.

Now, each of Greeley’s 27 schools has at least a part-time counselor and social worker. There is a small army of attendance workers who try to track down missing high school students. Class sizes are smaller. Every student has a Chromebook. The summer program has grown.

The federal dollars turned out to be a radical experiment in funding schools based on student need, with Pilch and school officials in high-poverty areas across the country receiving a stunning windfall. But the money is now dwindling and must be budgeted in the next two years. That means the country is hurtling back toward a status quo that defies the advice of experts of many stripes.

“When the COVID relief funds run out, that big gain in school funding equity will evaporate if states don’t step up,” said Zahava Stadler of The Education Trust, an advocacy group that focuses on disadvantaged children.

There’s significant agreement that low-income children need more funding for their education — perhaps a lot more

Before the pandemic, children from low-income families attended school districts with roughly the same amount of funding as non-poor children did, according to two recent studies.

That’s an unheralded victory. Students in poverty aren’t typically getting less, as is widely assumed.

In another sense, though, the victory is a hollow one. Experts who study these issues say that the same amount of funding isn’t enough: Schools serving low-income students should get more.

“The field has come to a consensus that high-poverty kids need more resources than advantaged kids,” said Lori Taylor, a school finance researcher at Texas A&M University.

Even some right-of-center organizations and researchers who question spending more as a strategy for improving schools, agree.

“You want to pay more money to kids that need more help, that are needy in various ways,” said Eric Hanushek, a fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution and a prominent skeptic of school funding increases.

How much more do high-poverty schools need? Here, there’s no agreement. But one recent study is the first effort to come up with a nationwide estimate.

Researchers from the Shanker Institute, a think tank affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers, statistically estimated how much money it would take to get every district in the country to recent average scores on national reading and math tests.

Some experts, including Hanushek, are skeptical of this study’s approach. Even researchers who use it acknowledge that it’s more like a statistically informed prediction than an exact science. Some districts that spend a lot on schools, including many in New York, don’t actually achieve the average outcomes that this study would predict.

But it’s a useful starting point for discussions about how much more children in poverty and their schools need.

The study’s conclusion: High-poverty districts in most of the country need more money to even get close to the performance of affluent districts.

In Greeley, it would take $2,000 more per student. Baltimore needs nearly $10,000 more per pupil. Schools in Selma, Alabama, need a breathtaking $17,000 more per kid. The typical high-poverty district needs close to $6,000 more, the study estimates.

Many factors drive costs up. Rural districts and those in high cost-of-living areas generally need more. Another particularly important factor is child poverty.

In total, it would cost $105 billion to fill in all these funding gaps every year — a major increase on the $771 billion in funding K-12 schools received in 2020. And that probably underestimates the cost, since the research is based on data before pandemic-induced learning loss.

“This is a tremendous figure,” wrote the Shanker Institute researchers. “It may even sound like an impossible gap to bridge.”

Poverty presents educational obstacles for children

Another way of thinking about that $105 billion number is as a rough estimate of unequal opportunity outside of school facing children from low-income families.

Consider: Children in poverty are more likely to be exposed to pollution and lead, which affects brain development. They’re more likely to have asthma that causes them to miss school frequently.

They’re more likely to be homeless, face eviction, or move around a lot, switching schools frequently.

They’re more likely to be exposed to violence.

They’re less likely to have enough healthy food to eat every day.

They’re less likely to receive preventative medical and dental care and less likely to receive needed treatment for mental health issues.

They’re less likely to be raised by two parents.

They’re less likely to have internet access at home to do homework.

They’re less likely to go to summer camps or to visit museums, among other enrichment activities.

Most of these factors have been linked to lower reading and math achievement. “It turns out that one of the biggest predictors of student performance is things that happen outside of school and not just the effects of school environments,” said Margot Jackson, a Brown University sociologist who studies inequality and child poverty.

These and other hurdles in mind, $105 billion doesn’t seem so surprising.

The point of listing the challenges that many children in poverty face is to help policymakers address them, including by improving how schools are funded — not to stigmatize low-income families.

The difference between low-income and affluent parents is not the aspirations they have for their children, said Jackson, but simply the money they have to buy things like safe and stable housing or enriching summer programs.

“Families across the economic distribution have highly similar values about parenting,” said Jackson.

Child poverty is not inevitable. Giving families money can directly reduce or eliminate it, and improves children’s outcomes in school, too.

But America’s child poverty numbers are going up now that the expanded child tax credit for families, which provided $3,000 annually per school-age child, has expired.

Poverty affects schools, but funding can help level the playing field

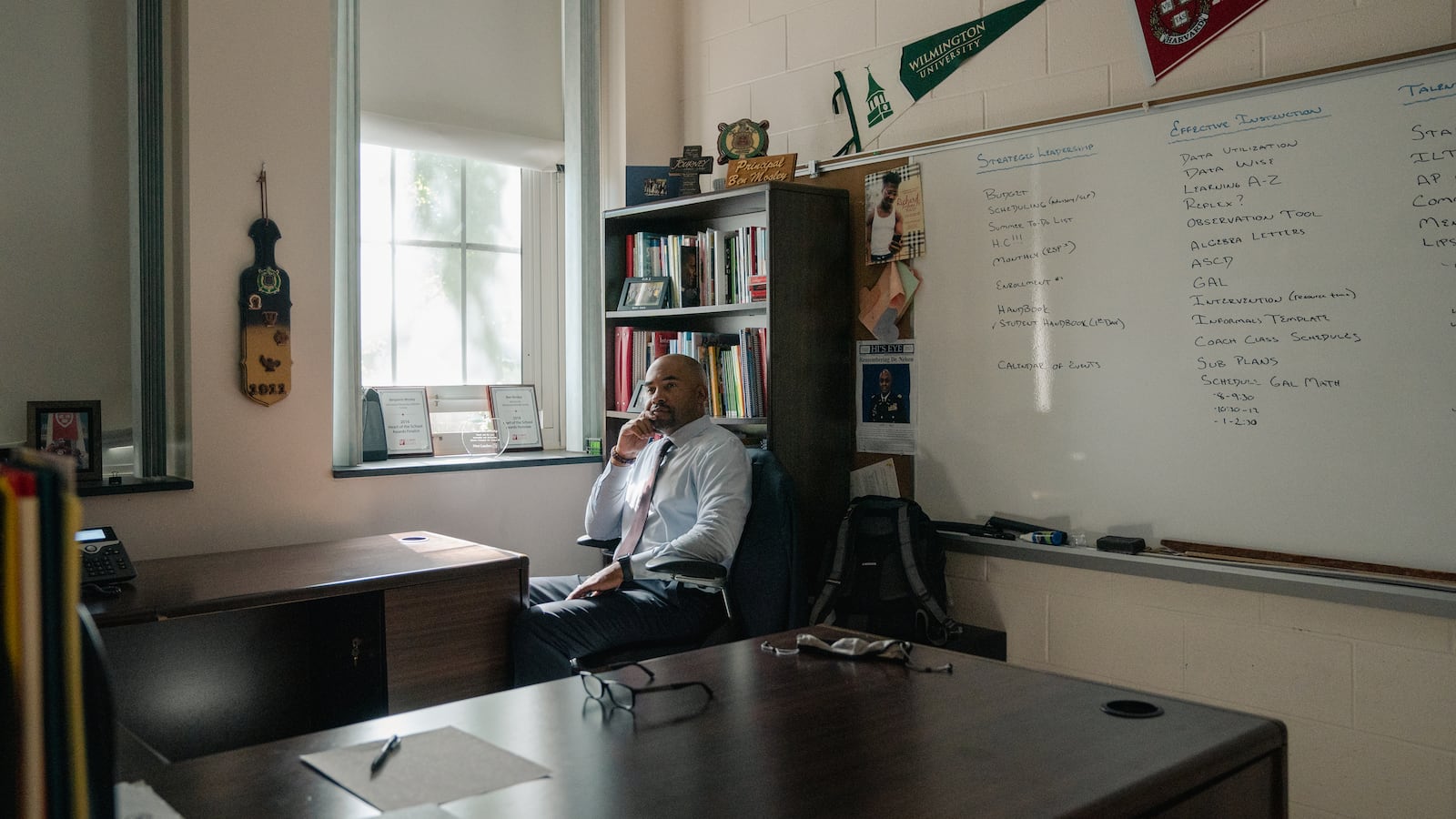

On a bright spring morning earlier this year, Benjamin Mosley, the principal of Glenmount Elementary/Middle School in Northeast Baltimore, stood outside, welcoming students as they filed in. As he walked through the hallways, he greeted students by name, fist-bumping, hugging, cajoling, asking about their lives.

Mosley, a former middle school English teacher, has been the principal of the school for eight years, and during that time he’s prioritized creating a warm environment. In the most recent school survey, the vast majority of parents who responded gave the school high marks.

Mosley doesn’t focus on the fact that most of the children at Glenmount come from low-income families. “I don’t know what child is in poverty,” he said. “I hold every student accountable with high expectations.”

But Mosley is also aware of all of the ways that poverty affects the school. The housing instability so many families face, for one, leads more students to switch in and out of Glenmount.

“We had a kid enroll last week!” he exclaimed, speaking in his office with two weeks left in the school year. “It impacts the psyche of teachers.”

Mosley estimates that only about a quarter of students end up as Glenmount “life-longers,” meaning they remain in the school from kindergarten through eighth grade. That’s hard on the kids who are regularly switching schools, and a challenge for teachers, who have to adapt to those who enter class in the middle of a year. Research has found that having students enter mid-year disrupts learning of other kids in the class.

On that morning, Mosley encountered another challenge. He popped into the class of a middle school math teacher and found students barely paying attention to a warm-up exercise that seemed more appropriate for early elementary students.

“The students weren’t engaged,” Mosley said as he stepped out of the teacher’s classroom, frustrated. “He’s talking to himself.”

This teacher had been struggling for some time, and Mosley was wrestling with what to do, as he wasn’t sure whether he could find a better replacement. “What’s worse: Someone who’s ineffective at teaching or an empty classroom?” Mosley wondered aloud in the hallway.

Research has long found that there is essentially a tax on schools with more low-income and more Black and Hispanic students: Those schools have a harder time finding and keeping teachers, a key reason that they usually have more inexperienced educators.

The list of extra costs high-poverty schools face goes on. Children in poverty are more likely to be identified as having a disability, which entitles them to additional services.

Low-income children may also experience more trauma outside school, which means schools often need more counselors.

“They can come to me, but there are times it’s like a waiting room in here,” said Jeanette Placeres, a counselor at Glenmount.

Of course, these challenges show up in middle class and affluent schools too, but they are more prevalent in poor areas — and funding typically does not keep pace.

The Baltimore area is racially and economically segregated in part due to a history of government policies that concentrated low-income Black families in certain parts of the city.

Today, about 1 in 3 Baltimore children fall below the federal poverty line, which is one of the highest rates in the state and the country. For a family of four, poverty is defined as having a household income of just $26,500. Many other families are just above that threshold.

That’s the main reason the Shanker study estimates Baltimore needs so much more funding than surrounding districts, despite the fact that it already gets somewhat more than nearby schools.

“Due in no small part to the segregation-fueled concentration of poverty within its borders, Baltimore City is a large peninsula of severely inadequate funding,” wrote the researchers.

Additional money for schools now can only do so much to address the cascading consequences of poverty and segregation. But recent studies suggest that when schools find themselves with more funding, students benefit. Their math and reading scores tend to improve, and they are more likely to graduate from high school and enroll in college. These gains tend to be small but meaningful, and often students in poverty benefit the most from additional school spending.

Many parents also believe that money can make a difference. For years, the most common complaint about public schools from parents and teachers has been a lack of resources, polling shows. Another recent poll found that three-quarters of parents were supportive of providing extra funding for students with additional needs.

“Do we need more funding? Absolutely,” said Terrence Allen, who walks his second-grade grandson to Glenmount every morning. “You get more money, you can do more.”

To be clear, how dollars are spent is crucial too. Some high-poverty districts seem to have enough money but still see achievement lag. Certainly, in many cases, schools could spend money more effectively.

Take Mosley’s struggle to find a better math teacher. Yes, higher salaries for all teachers would probably help. But so could using existing funds to raise pay for teaching roles in hard-to-fill subjects like math, something that is not permitted by the city’s teachers’ contract.

There is no real tension between these ideas, though. Additional money could be paired with efforts to use those funds as effectively as possible.

“It’s not just money — it’s money spent well, invested well, with a lot of other things,” said Sonja Santelises, CEO of Baltimore public schools.

Schools brace for return to broken system

At this point, it’s impossible to issue a verdict on the COVID-era experiment in pumping money into high-poverty schools. There’s no evidence yet of how much of a difference the money has made, and tracking systems created by the federal government and states have been of limited use.

To a person, though, educators like Mosley say the dollars have been essential for addressing both the pandemic’s health and academic challenges.

At Glenmount, the funding has brought in extra support staff who can work with students in small groups, new science and social studies teachers so those courses are available all year for middle schoolers, and a new drama program, Mosley said. The district as a whole has used the money to add summer programming, hire mental health staff, and upgrade buildings, among many other things.

“Without the money, we would have been in chaos regarding coverage and following COVID protocols,” Mosley said. “We could not have afforded the after-school enrichment and instructional programs that were led by classroom teachers.”

But the last of the federal money has to be budgeted by September 2024, and once schools fall off that funding cliff, they will likely land back on the old funding structure.

The reasons are predictable, even understandable. Many voters don’t want higher taxes. State legislators from better-off communities advocate for their own local schools. (This cuts across political lines, with many purportedly progressive states funding schools in a not-at-all progressive way.)

Improving funding systems is certainly not financially or politically impossible. Maryland, for instance, approved additional funding for high-poverty schools last year, which is another reason Mosley finds himself flush with funding. But state-level politics are often challenging.

Pilch, the Greeley superintendent, says there have long been discussions in Colorado over how to improve school funding. But voters have rejected tax raises to increase funding, making it politically fraught to overhaul the formula. Just recently, an effort to put a school funding measure on the ballot failed.

“Every year we talk about the state formula, and every year it becomes apparent it’s too complex to try to change it,” she said.

States spend wildly different amounts on education, and low-income families are often concentrated in states that spend less. The disparities this creates are hard to solve without more federal funding.

But President Biden’s proposal to double funding for Title I, the formula that sends money to high-poverty schools, has gone nowhere. Instead, Congress approved only an anemic bump. This year, Biden has once again proposed a large increase, but that’s seen as a long shot.

So schools and educators are bracing for a return to the old system.

“Money is a variable — it’s not the end all, be all,” said Mosley. “But without the money, you’re already starting the race miles back from everyone else.”

READ NEXT: New York schools see a big disconnect between spending and test scores. Why?

Matt Barnum is a national reporter covering education policy, politics, and research. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.