Some Chicago aldermen want school district officials to meet with City Council quarterly, but a proposal to make that happen failed to pass Wednesday.

Under the ordinance, the measure would have temporarily withheld city money for certain school projects if Chicago Public Schools officials didn’t show up. That turned out to be a deal breaker for many aldermen on the committee, which held a virtual meeting Wednesday.

The vote was tied — and therefore, failed — with seven voting in favor and seven voting against.

“I currently have three projects in the hopper and I don’t want to get in the way of my own best interest,” said Ald. Susan Sadlowski Garza, a former school counselor and Chicago Teachers Union member. She said quarterly meetings are “not a huge ask.”

Ald. Sophia King, who is running for mayor, put forward the ordinance during a committee meeting after being frustrated with the district’s lack of response to her budget questions.

“The threats of resources being withheld could very easily be waylaid, if CPS would just show up,” King said, noting that she reached out to district chief Pedro Martinez “quietly and subtly” to try to get questions answered about the school district’s budget “to no avail.”

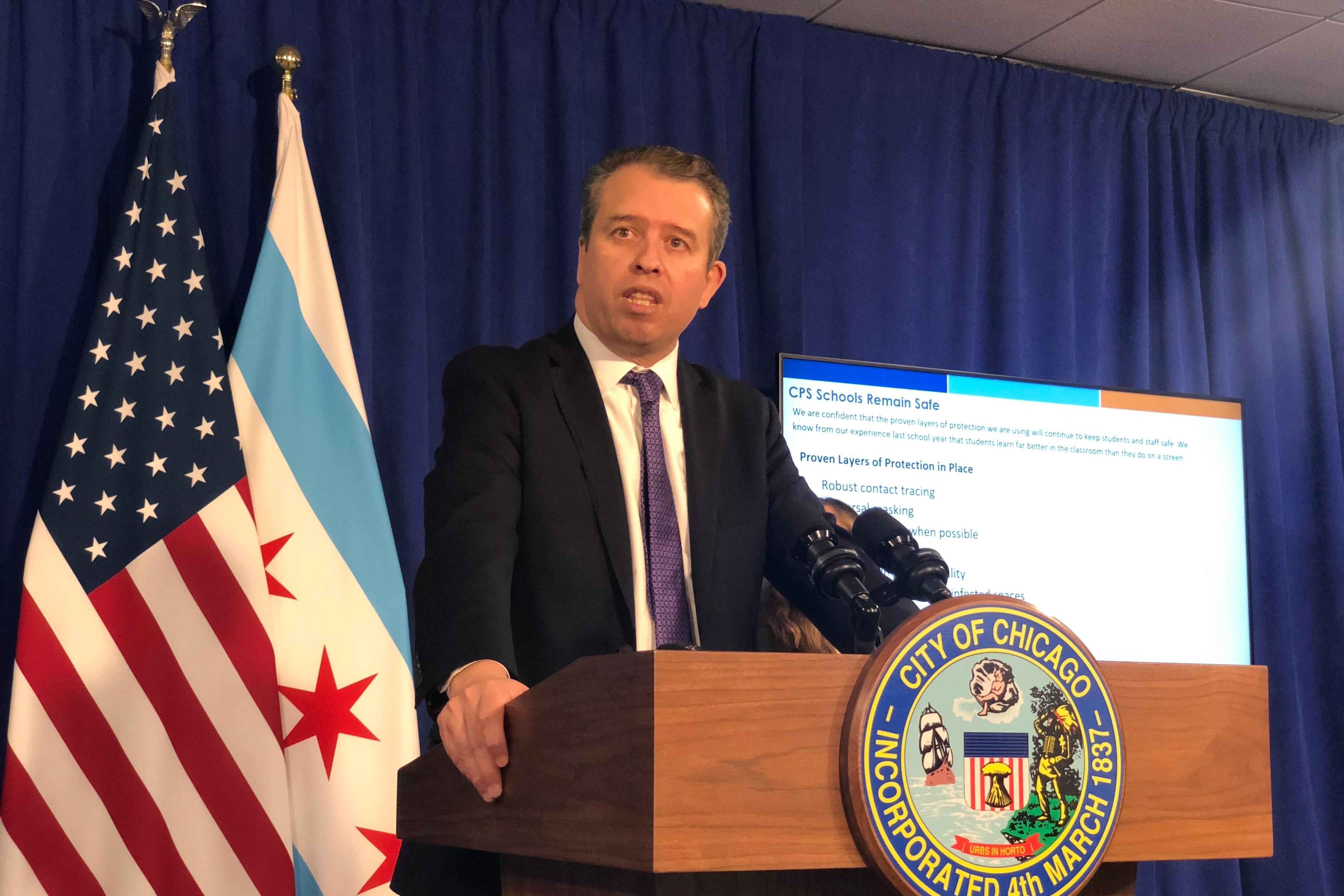

Chuck Swirsky, senior advisor to Martinez, called it a “harmful ordinance” that would jeopardize school construction and infrastructure projects.

“You have our numbers, and we answer each time you call and I mean no matter what time of day it is,” Swirsky said. “We wholeheartedly value the genuine relationships and partnerships that we have fostered with City Council members.”

But Chicago Public Schools officials rarely appear before aldermen in public meetings. The Committee on Education and Child Development also rarely meets, despite attempts by council members to call meetings.

It was the first time King led a meeting as the vice chair of the Committee on Education and Child Development, which has been without a leader since June when Ald. Michael Scott Jr. resigned to take a job in the private sector. Mayor Lori Lightfoot has since appointed Scott to the school board and attempted to appoint an ally and bypass King.

The discussion comes after a report, prepared by the district with help from a consulting firm, released last week outlined the costs the city could shift to the school district once it transitions to an elected school board. It outlines hypothetical cost shifts on everything from school construction funding to water bills to summer programs.

The city already started shifting costs to Chicago Public Schools in 2020 when it started requiring the school district to pay into a city pension fund that covers some school employees.

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org.