Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

The Chicago Board of Education wants to remove police officers from schools starting next school year, according to a resolution included in the agenda for Thursday’s board meeting.

The resolution directs CPS CEO Pedro Martinez to come up with a new policy by June 27 that would introduce a “holistic approach to school safety” at district schools, such as implementing restorative justice practices, which focus on resolving a conflict instead of punishment.

That policy “must make explicit that the use of [school resource officers] within District schools will end by the start of the 2024-2025 school year,” the resolution said. (Find the resolution on page 15 of your PDF reader.)

The resolution nods to the district’s shift in student discipline to more restorative practices, which has led to “significant progress” in reducing suspensions. However, the resolution notes that disparities in suspension rates are disproportionately higher for students with disabilities and Black students, compared to their Hispanic and white peers.

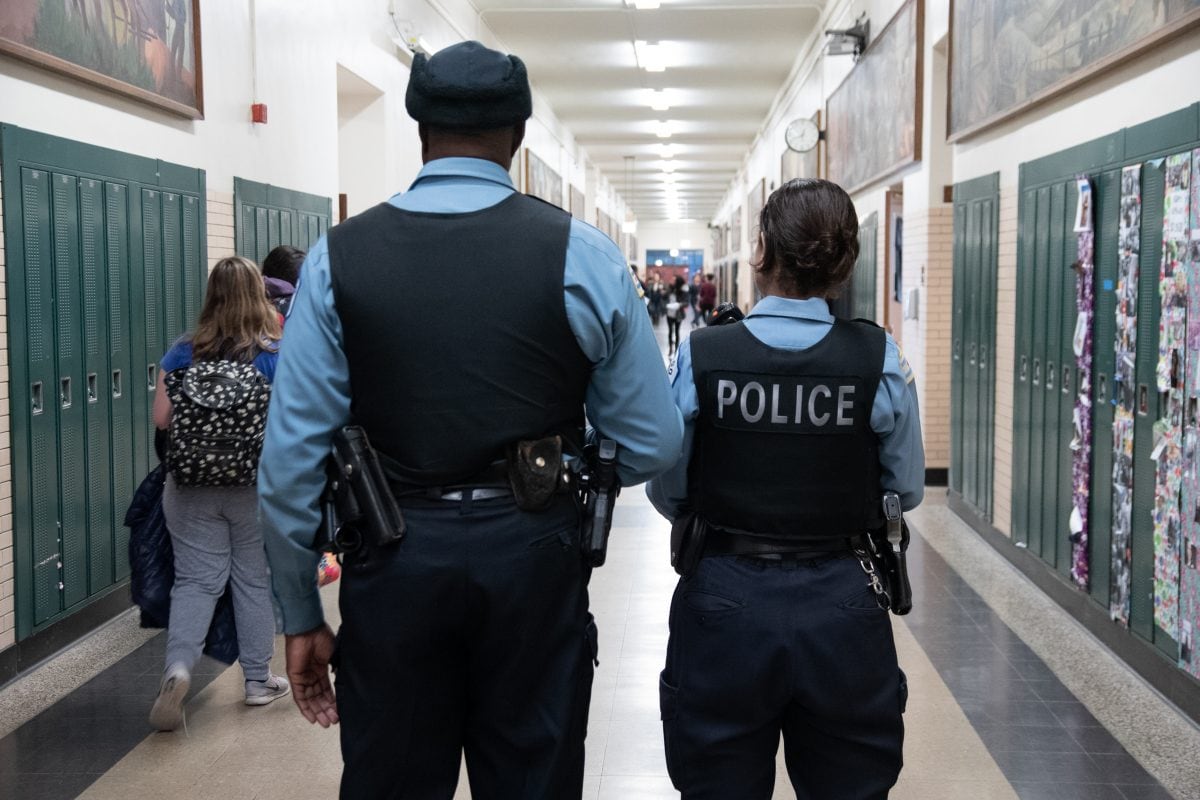

Most CPS schools don’t have school resource officers who, unlike security guards, are trained and employed by the Chicago Police Department, but are stationed in schools full-time. If passed, the resolution would directly impact 39 schools – all high schools – that have a total of 57 officers on campus, according to the resolution and district officials. Fourteen schools voted to remove a total of 28 officers and instead received a total of $3.9 million for “alternative safety interventions,” including for restorative justice and social service coordinators, the resolution said. CPS also employs more than 1,400 security guards at schools, according to staffing data from the end of December 2023.

Schools that have voted to keep their officers have cited a variety of reasons for doing so, including that in some cases, school resource officers have strong relationships with students. Opponents of police on campus argue that the presence of officers can lead to more punitive student discipline and can leave children feeling unsafe.

Last month, Nadig Newspapers and WBEZ reported that the board was planning to remove Chicago Police Department officers from schools. Mayor Brandon Johnson later confirmed to WBEZ that he’s in support of such a plan.

The resolution, which the board is slated to vote on Thursday, represents Johnson’s hand-picked school board’s clearest statements on removing police officers from Chicago schools. As a mayoral candidate, Johnson had said police officers “have no place in schools,” WBEZ and the Chicago Sun-Times reported. However, last year, he told the outlet he would leave the decision up to LSCs.

The resolution said the district would continue to partner with the Chicago Police Department, but district officials did not immediately explain what that relationship would look like.

Having police stationed inside Chicago schools came under scrutiny in 2019 as part of the police department’s federal consent decree. In 2020, amid protests and the racial reckoning that swept the country after George Floyd’s murder at the hands of Minneapolis police, Chicago schools began voting one-by-one on whether or not to keep their school resource officers.

Driven by similar issues, Denver Public Schools removed police from schools in 2020 and 2021, but its work to implement a new school safety policy, as Chicago’s board is seeking, was derailed by the pandemic. The Denver school board reversed its decision last June after a shooting inside a high school.

In 2022, the Chicago school board reduced its contract with the police department from more than $30 million to roughly $10 million and allocated money for schools to implement alternatives to police, such as restorative justice counselors. The contract was renewed last summer for $10.3 million and about $4 million to improve school climate was separately allocated to schools that had removed their officers.

Research from the University of Chicago released last fall found an improvement in student engagement and a decline in suspensions at schools that had implemented restorative practices in recent years.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org.