Chicago voters will — for the first time — elect school board members this Nov. 5.

After decades of advocacy and several twists and turns, candidates have filed to run, even as open questions remain around ballot access, voter eligibility, and member compensation.

Some claim this transition as a win for democracy, but neither appointed nor elected selection guarantees an effective board. Awareness of this election remains low, as does understanding of what a school board does. The board’s decisions, and ultimately, whether our public schools are effective and equitable, depends on their focus, behaviors, and work.

It matters now more than ever that voters understand why school boards exist, what the Chicago Board of Education’s responsibilities are, and what effective governance looks like, so we can make informed choices this fall.

The 21 school board members — 10 of them elected — will be sworn in on Jan. 15, 2025. These members will have significant influence over how future Chicago school boards will work, the board’s relationship to district leadership, and ultimately, how effective our schools are.

The change in structure is an opportunity to shift from a governance model based on precedent and adult comfort — “this is how we’ve always done things” — to a governance model that is intentionally designed to focus on, and most effectively improve, outcomes for the students of our city.

What is a school board anyway?

To make informed decisions that lead to an effective board, voters must understand what a school board is, what it does, and how it works effectively.

School districts do not exist on their own. They are creatures of state law. In Illinois, Article X of the state Constitution establishes a “fundamental goal” of “educational development of all persons to the limits of their capacities”, that the state “shall provide for an efficient system of high quality public educational institutions and services”, and that it shall have “primary responsibility for financing the system of public education.”

That is, we have public schools to educate all students in our community — to increase what our students know and can do.

The Illinois School Code sets overall expectations of districts and of boards and carves out specific rules for Chicago in Article 34, which was amended in 2021 to make the board elected.

In Chicago, the school board sits below the community; it exists to represent the vision and values of the community, who are the “moral owners” of the district.

The board exists to govern — not manage — for the whole community. This includes students and their families, and also residents who have no “customer” relationship with public schools. These stakeholders have many ideas about which student outcomes should be focused on, and what means should be used to do so.

Elected school board members should engage the whole community to understand the vision they have for students, and the values they have for how this work is done. They must bring coherence to the expectations shared by this diverse community to provide a clear definition of success. This enables the district’s leadership and staff to effectively pursue a common community vision while adhering to a shared set of values.

The board is also responsible for setting and monitoring goals, and developing and passing policies, on behalf of the community. The board is responsible for hiring, supervising, and evaluating a CEO, as well as evaluating its own work. And per statute and its own rules, it has a number of administrative functions, such as approving a budget.

How is Chicago’s school board unique?

Chicago’s school board will shift from seven appointed members to 21 members. For a two-year period beginning in January 2025, 10 members will be elected and 11 will continue to be appointed by the mayor. In 2027, all 21 members will be elected.

As Senate President Don Harmon (D-Oak Park) put it earlier this year, Chicago is creating “a new democratic form of government from whole cloth.”

This is not the first time that Chicagoans will vote for people to make decisions about their local public schools. Since 1988, Local School Councils (LSCs) have played a key role in governing individual schools. An effective LSC works just like an effective school board: The LSC sits below the school community, engaging with them to understand and represent their vision and values as moral owners, sets and monitors goals, hires and supervises and evaluates the principal, evaluates its own function, and fulfills other duties like budget approval.

While LSC training has serious issues and too many LSCs are ineffectual in supporting school improvement, this experience may be a helpful resource for future boards. But unlike LSCs, the school board is responsible for results across the entire district.

CPS has delivered progress for students through recent decades, often through times of economic and political challenge, but many of these improvements resulted from professional educators’ work with little Board support.

However, some challenges aren’t easily solvable at the school level. This new governing body will confront decades of segregation and disinvestment that have led to very different experiences for students situated differently in our city.

A recent Public Agenda survey finds that “more city residents trust teachers and principals to look out for students than trust the teachers union, board of education, CPS central office, or mayor to do so” — indeed, half or fewer of city residents trust the Board or district to look out for students. Only four in ten think an elected board will serve students better than an appointed board.

With more changes coming, the Board must govern effectively to face these challenges as a district.

What makes a school board effective?

While school boards make big decisions that impact many aspects of students’ educational experience and outcomes, research on what these boards actually do is limited and often relies on small samples of school board member surveys. These efforts can also provoke political resistance, especially when they focus on student outcomes.

However, ongoing work is shedding more light on what makes school boards effective, and the findings reinforce some of what is known about the characteristics of effective school boards.

Based on the evidence of other districts, whether board members are appointed or elected doesn’t seem to be tightly correlated with effectiveness — but how they work is strongly correlated.

So what should school boards do?

Specific behaviors are associated with improving student achievement. According to a review of existing research compiled by the National Association of School Boards, effective school boards:

- engage with and listen to the community, and collaborate with staff and as a board around strong shared beliefs and values about what is possible for students and their ability to learn.

- lead with strong collaboration and mutual trust as a united team with the superintendent, assess themselves, and work to train and develop their own knowledge and skills with a commitment to continuous improvement.

- commit to a vision of high expectations for student achievement, define clear goals toward it, align and sustain resources towards these goals, embrace and monitor data, communicate progress to the community, and stay focused on improving student achievement (rather than operational issues).

What do these evidence-based best practices about what effective school boards do imply for the Chicago Board of Education?

The district, under the governance of the current appointed board, is going through the process of creating a strategic plan. Staff have incorporated many opportunities for the community to learn about the plan and to voice some reactions.

However, rather than asking the community what is important to them — their vision for our students — the district has developed a plan and then asked for feedback on these methods. This is the reverse of effective practice.

The new board and its successors will have the chance to listen to the community about their vision to identify what outcomes the community feels are most important for our students. This can only happen if the board engages communities by meeting them where they are, getting a broad and representative voice, and asking questions about the community’s vision, rather than feedback about specific methods.

The next step of effective governance is to create focus by setting clear goals reflecting both the community’s vision and the realities of the current state.

Goals are the foundation to make all the subsequent decisions well. Goals allow the board to hold district staff accountable for student outcomes — the purpose of the district — rather than focusing on adult interests or inputs. In particular, clear goals enable the board to monitor progress.

The more the board does this work while staying out of specific methods that district staff select, the more effectively staff can focus and the more likely it is that we make progress so the most important student outcomes are improved.

Finally, how the board operates is crucial to rebuild trust, engagement, and voice. Based on the last several decades, many stakeholders have well-founded concerns about how decisions are made, whether their well-being and perspectives are considered, and whether the outcomes of those decisions have been accurately conveyed.

This distrust can drive the community’s attention to securing inputs for specific schools or neighborhoods, rather than focusing on outcomes. This can move the board to respond primarily to those who have voice and privilege. This can lead to inequity, and through loss of focus, less effective system-wide governance.

What can you do to help Chicago’s elected school board be effective?

There are four things voters can do to help align what candidates do to campaign with what board members do to govern effectively.

First, ask candidates the right questions. This starts with understanding the role of the board.

Candidates are already making statements about who they are, how the district should work, or what they will do on their websites, in campaign materials, and in forums and interviews. Some of these statements are aligned with what boards can do, and even what effective boards do.

But many are not. They make promises that are outside the authority of an individual board member or the board as a whole, focus on methods over outcomes, or prioritize specific subsets of the city rather than the community as a whole.

Ask potential board members what the role of the board is and how they will act to make the board effective — how they will engage with the community, collaborate with each other and with staff, train and develop their own knowledge and skills to improve, and about how they will set and monitor goals for student outcomes.

Second, select candidates who commit to being effective, and help others do the same.

When candidates express their understanding and commitment to effective board behaviors, share this with others in your community — and when they don’t, share that too.

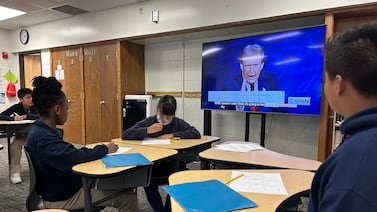

Awareness remains low — 63% of residents are not aware of the transition to an elected board. Turnout in recent elections has been generally low, and research finds that there is often a pronounced demographic divergence between the student population and those who cast ballots in school board elections.

Even on the ballot, school board elections will show up after every other elected office, followed only by the numerous votes on retaining judges.

Make a plan to vote, and to activate your communities, so board members who are committed to effective governance have a chance to serve, and all board members realize that their voters care about effectiveness.

Third, give candidates (and board members) input.

Chicagoans have varied opinions about what is important for our students to learn, about the priorities among them, and about the values by which our schools should abide. It is important to have conversations about these questions, and it is the board’s job to represent the community’s views.

Unfortunately, the attention of advocates, candidates, and voters has disproportionately been on factors of identity, affiliation, and ideology rather than goals for our students. Even with competent and dedicated district leadership, staff, and educators, we’re less likely to achieve the outcomes our students deserve if the board doesn’t do its job well. We must all give the board input on what is most important for the district to achieve, so these outcomes are as likely as possible.

Finally, hold board members accountable.

Accountability isn’t just about consequences; even more powerful than what happens after the decisions are made is setting clear expectations up front of what needs to be accomplished. Just as the board is responsible for holding the CEO and their staff accountable to deliver the outcomes that our students need and deserve, we as voters are responsible to hold the members of the board accountable to do their job of governance.

We must expect them to focus on what’s best for students, listen to the community’s vision, communicate the current state and progress, and provide clarity on plans for the future. If we as voters prioritize a district that works for all our kids rather than prescribing specific methods or focusing on local needs or in response to adult interests, we will have the best chance of a district that will navigate upcoming challenges to continue improving outcomes for all of our students.

This historic governance transition poses risks, but also opportunities. If voters engage with candidates now, through the election, and beyond, we will give the board the best chance to operate effectively, so our district has the best chance of delivering our students the outcomes they need and deserve.

Sendhil Revuluri is a parent of two CPS students, a former teacher, and former vice president of the Chicago Board of Education from June 2019 to December 2022.