Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

New York City’s Education Department is severely out of compliance with a federal law mandating regular inspections of school buildings containing asbestos, an audit released Wednesday by comptroller Brad Lander found.

Out of the city’s roughly 1,600 schools, a whopping 80% have been identified to have asbestos and are required by federal law to be inspected by an accredited professional once every three years. Yet, only 18% of the more-than 1,400 schools containing asbestos had such inspections between 2021 and 2024, the audit found.

School buildings with asbestos are also required to have routine inspections by a trained employee, such as a custodian, every six months. But the city only began systematically tracking those inspections in 2023 and completed them at just 22% of schools between 2023 and 2024, the audit revealed.

“[The Education Department] has stunningly failed to follow the minimum national standard for asbestos management for years,” Lander said in a statement. “I am urging the Adams Administration to take swift action to come into compliance because no parent, teacher, or school staffer should feel unsafe walking into a school.”

The audit advises the Education Department to create new policies, tracking systems, and accountability plans to quickly improve its compliance.

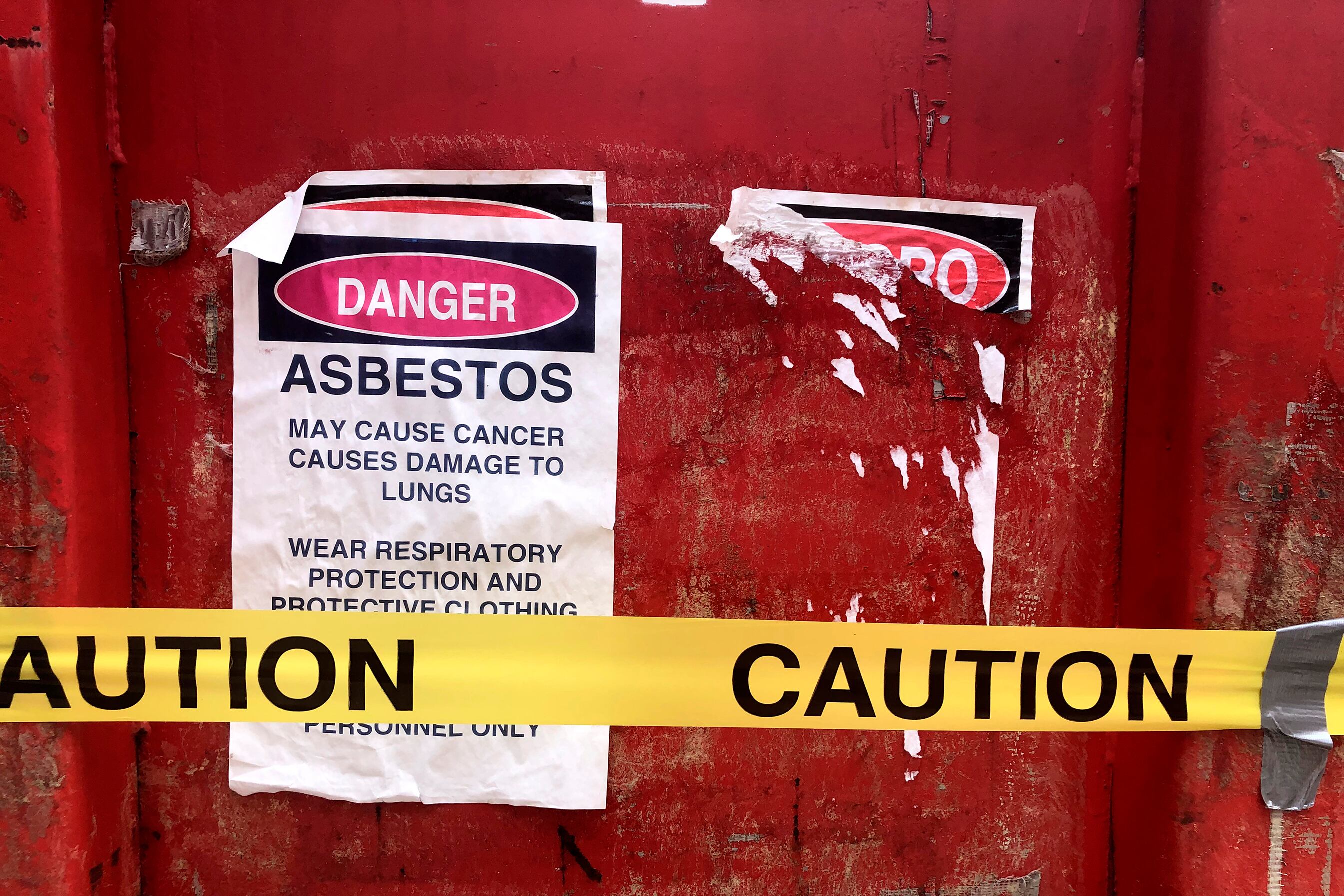

Asbestos can cause serious health complications including cancer when inhaled. The compound was widely used in school construction during the 20th century, and it can be found in insulation, flooring, and air conditioning equipment. Asbestos can be safely left in buildings as long as it’s intact, but when materials containing asbestos start to degrade, it becomes a safety risk.

Education Department officials claimed there was no risk of exposure because of the city’s abatement practices, according to Lander’s report — an assertion with which the auditors disagreed.

The 1986 Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act, or AHERA, mandates regular inspections. Failure to comply with the law can result in financial penalties, according to the audit.

The city school system has a history of falling short on its asbestos inspection obligations: The start of school in 1993 had to be delayed by more than a week after officials had to scramble to conduct hundreds of last-minute emergency inspections.

From 1997 onward, the city completed an average of just 11% of the required triennial inspections in each three year stretch, the audit found.

The comptroller’s audit found the recent rates of inspections were the lowest in Brooklyn, where just 13% of school buildings containing asbestos got their required triennial review between 2021 and 2024. The highest rate was in the Bronx, where 25% of schools received the required inspection.

City officials have also maintained spotty records of their efforts to train custodians to conduct the twice yearly surveillance inspections and of whether those inspections were completed, the audit found. The system improved starting in 2023, but still shows the city completing only a fraction of the required inspections, auditors said.

The auditors also pointed out that some 60 school buildings may be improperly listed as containing asbestos — and receiving unnecessary inspections — because the city’s recordkeeping is out of date.

In a letter to Lander’s office responding to the audit, Education Department Chief Operating Officer Emma Vadehra agreed to all of the comptroller’s recommendations.

The department is hiring an executive director of health and safety to oversee all building safety work citywide, along with five borough-based deputies, and is working to digitize its asbestos inspection records, she added.

Custodian engineers are trained on asbestos and complete “daily walkthroughs” of their buildings that include checking the condition of materials that contain asbestos, Vadehra said.

An Education Department spokesperson noted that the agency requires testing before doing any work on a building.

Michael Elsen-Rooney is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Michael at melsen-rooney@chalkbeat.org