Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

Federico Zegarra, a special education teacher, spent a recent Thursday morning preparing lesson plans in his coworker’s classroom while her class was in session.

Outside of the assistant principals’ office, three students received reading intervention at a table. What used to be a “mindfulness room” down the hall is now part dean’s office, part instructional space, and part study hall for students.

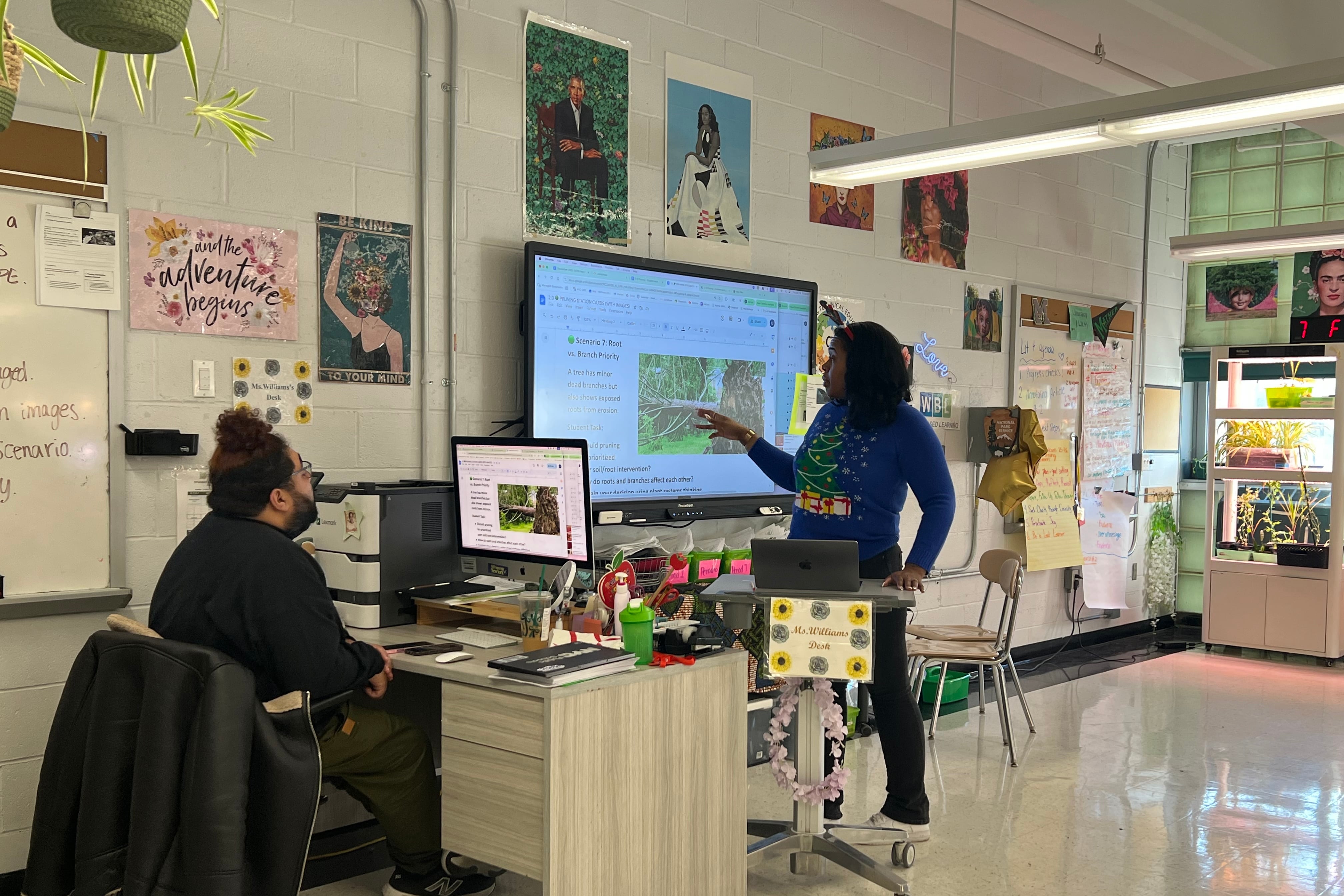

This is what complying with New York’s class size reduction law looks like at Manhattan’s Stephen T. Mather Building Arts & Craftsmanship High School.

While Zegarra and his colleagues agree that having smaller class sizes has made a world of a difference for them and their roughly 340 students, it’s meant playing a game of jigsaw puzzle in the building they share with four other schools.

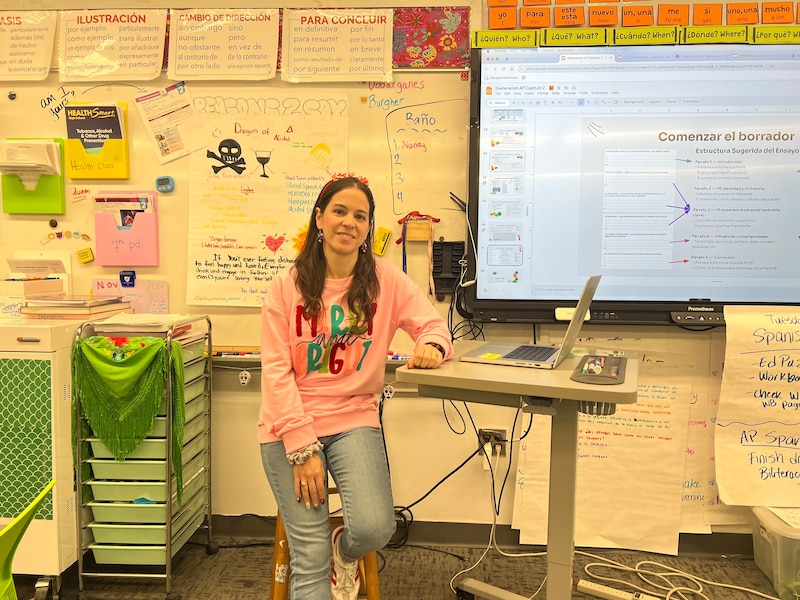

“People are teaching in offices, people are teaching in the hallway at some point because we just don’t have enough classrooms,” said Ivette Dobarganes, a Spanish teacher and United Federation of Teachers chapter leader at the school.

The end of this semester marks the halfway point in the five-year implementation period of the class size law, which state lawmakers passed in 2022. The law requires New York City schools to have at most 20 students per class in grades K-3, 23 students for grades 4-8, and 25 students for grades 9-12 by September 2028.

Last month, the city announced that about 64% of public school classrooms met those limits, surpassing the required 60%, but only after thousands of classes received exemptions.

Educators with smaller classes are raving about the change. Out of about 50 educators who responded to a Chalkbeat survey about the class size mandate, nearly three-quarters said that their schools have reduced class sizes and they have seen positive changes in their classrooms. Educators said they could give students more attention, more detailed feedback, and allow for greater participation in class.

They’re also noticing fewer behavioral issues in students, and they’re able to reach out to parents in a more manageable way. They’re feeling less stressed about their workload and have energy to give to students.

But experts, advocates, teachers, and a lawmaker who spoke to Chalkbeat are also concerned the city is falling behind in its efforts to meet the mandate. They worry the second half of the implementation process will prove to be more challenging, and some teachers who responded to Chalkbeat’s survey expressed doubt that their class sizes will ever be reduced.

Education Department officials emphasized that the city is in compliance with the current target of the class size mandate.

“We remain committed to complying with state law and recognize that meeting the law’s future milestones of 80% and 100% will require an extensive commitment of resources,” Jenna Lyle, an Education Department spokesperson, said in a statement.

fall, the city spent $450 million on hiring new teachers and is planning to do a similar hiring spree next fall. To reach full compliance by 2028, the city must budget another $700 million for an additional 6,900 teachers, the Independent Budget Office said.

In a letter to Gov. Kathy Hochul on Monday, New York City Comptroller Brad Lander wrote that the city’s recent financial plan isn’t sufficient to cover expenses needed to meet next year’s 80% target and full compliance the following year. He refused to certify the Department of Education’s latest class size reduction plan. (The lack of certification does not carry legal implications, according to experts.)

Along with costs for additional teachers, classroom space remains a major concern.

According to the School Construction Authority, the city needs 70,000 more seats to meet the class size mandate. Over half of the educators who responded to Chalkbeat’s survey mentioned space as a challenge.

At Mather, which received city funding this year to hire six new teachers, nearly all classrooms are being used at all times, so teachers typically don’t have access to their desks to do their prep sessions and find whatever space they can.

But Mather’s teachers are still finding silver linings. For example, they agree that it’s created less isolation and more opportunities for teachers to learn from one another.

“We collaborate, we talk more,” Dobarganes said.

‘The biggest impact on education that I’ve ever seen’

Nicolina Mullins, from P.S. 146 in Howard Beach, Queens, has 18 students in her class, which she co-teaches with a special education teacher for students with disabilities alongside typically developing children. In her 24 years teaching Mullins previously had as many as 32 kids in a class.

She’s noticed more student engagement and fewer kids feeling overwhelmed with socializing. Her own mental health has also improved, and she can do more without having to bring as much work home.

Kelli Hesseltine, an English teacher at Manhattan’s High School for Math, Science and Engineering at City College, feels the same.

“I feel like I’m coming home every day less exhausted, and I just have more energy to reinvest in the relationships with students,” Hesseltine said. “I’ve been teaching for over 20 years, so I really cannot stress this enough that this has made the biggest impact on education that I’ve ever seen.”

Last year, she had five classes of 34 students each. This year, four of her classes have 25 students or less. The difference, she said, is “powerful.”

For starters, her classroom is less cramped. Before, she could barely walk between the tables. She now has time for every student to participate, and she’s able to give papers back to students within a week instead of a month.

When a student is struggling she now has more time to talk to parents regularly.

“Before it was always just about putting out the fire, but now it’s about celebrating wins,” Hesseltine said. She’s able to email parents to say, “‘I saw your kid do something awesome in class today.’”

To address space constraints, Hesseltine’s principal and parent teacher association worked to turn some office spaces into teacher work rooms.

“It’s actually really cool. We have a ‘quiet room’ and sort of a ‘loud work’ room, so teachers can be either meeting with each other or meeting with students in this one space,” Hesseltine said.

Bobson Wong, a math teacher at Bayside High School, never had his own desk or classroom, even before the class size reduction law. He said his Queens school, which has about 3,000 students, had to add more sessions to their staggered schedule to comply with the mandate.

Last year, students and teachers would either start their day during period two or three but this year, to accommodate smaller classes, some are starting their days during period four at 9:37 a.m. To reach full compliance, Wong said some students and teachers might eventually have to start during period five, which means their day would begin at 10:17 a.m. and end at 4:35 p.m., according to the school’s bell schedule.

The staggered schedule has created some logistical hurdles, Wong said. For example, it’s made it harder to schedule faculty meetings when everyone is on a different daily schedule.

For all of the logistical hurdles, however, Wong didn’t want to give the impression that smaller class sizes were a “bad thing,” Wong said. He emphasized that it’s not.

But as schools across the city work toward reaching full compliance, some teachers are worried about other unintended consequences.

Hesseltine estimated that her school is about 70% in compliance with the class size mandate, and if they don’t reach 100%, she fears it could create an equity issue within the teaching staff: How would her school decide who gets smaller class sizes and who doesn’t?

“I think we’re all kind of worried,” Hesseltine said. “Is there enough dedication to really making this happen 100% across the school, from state and from the city?”

Mullins, the Queens teacher, hopes other teachers will get to experience the same benefits of the law that she has.

“I hope all of my colleagues are able to benefit from it at some point because I’ll tell you,” Mullins said, “it definitely is a different world when you have [a] small classroom size.”

Correction: Jan. 2, 2026. This story initially included the Independent Budget Office projection based on 2023-24 school year data instead of figures accounting for current teachers and class sizes.

Jessica Shuran Yu is a New York City-based journalist. You can reach her at jshuranyu@chalkbeat.org.