Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

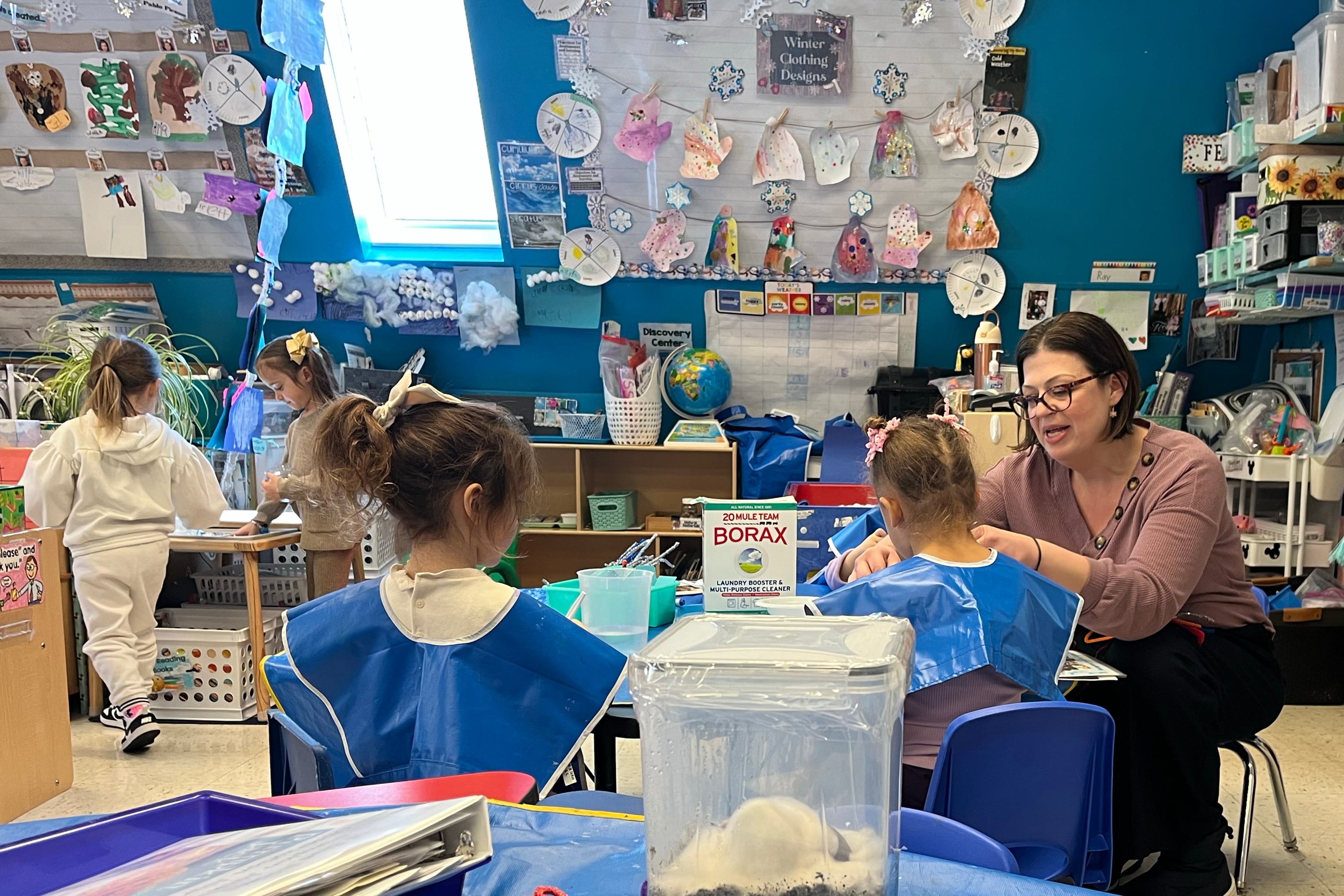

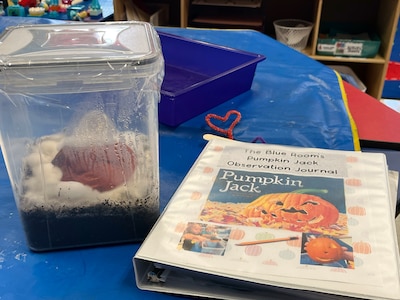

The 4-year-olds in Rebecca Schneider-Kaplan’s prekindergarten class are doing a science experiment designed to document the demise of a pumpkin named Jack.

Since October, Schneider-Kaplan has recorded their observations in a binder. The kids use paint and cotton balls to illustrate the mold swallowing Jack’s flesh.

In previous years, the pumpkin experiment stopped much sooner. But this class loves science, Schneider-Kaplan said, so she adapted.

Ushering a room full of pre-K students toward a learning goal requires constant improvisation. On a recent Tuesday morning at Stepping Stones Pre-School in Staten Island, Schneider-Kaplan held 11 pairs of eyes on a rotting pumpkin (seven students were missing because of the weather), while simultaneously sending a squirming child to the bathroom, keeping tabs on a boy who was more interested in pulling blocks off a shelf, and reminding multiple kids to keep their hands on their own bodies.

Schneider-Kaplan, who has taught for 18 years, would earn significantly more money if she did the same job at a public school down the road, rather than a private child care center contracted to run pre-K through the city’s Education Department. She would also get regular raises, health insurance, a pension, and additional pay for experience or extra training. And she’d enjoy the same perks as city teachers, with prep time, a lunch break, and summers and school holidays off.

The city has promised to fix the inequities for years, but an audit released by the city comptroller two years ago found that 90% of community-based lead teachers with master’s degrees still earned less than their early childhood counterparts who worked in public schools. In the Bronx and Brooklyn, some certified teachers start at less than $36,000 a year — close to $30,000 less than at public schools, the audit found.

Educators, who plan to hold a rally next week at City Hall, are angry that Mayor Zohran Mamdani is moving to expand care to 2-year-olds before addressing the existing inequities in the 3-year-old and 4-year-old programs.

“It’s just a complete lack of respect,” Schneider-Kaplan said. “I needed two degrees to become an early childhood educator, but I cannot afford to pay back my loans because I don’t make enough money.”

Early childhood wages are ‘impoverishing’ workers

The city’s subsidized early childhood system – which served nearly 160,000 babies and children last year – relies on a vast ecosystem of programs in public schools, neighborhood centers, and private homes.

This fall, the Mamdani administration will add 2,000 new, free spots for 2-year-olds — a first step toward meeting his campaign promise of universal subsidized child care for kids under age 5.

In a December report, Emmy Liss — who became the executive director of the mayor’s Office of Child Care just a few weeks after the report’s publication — wrote that subsidized early education programs were built in part as anti-poverty programs.

“It is somewhat ironic then that child care as a field is impoverishing its own workers, creating an entire class of working people who earn too little to provide for their families,” Liss wrote, adding that the city’s child care workers are almost entirely women of color.

“Since the time of slavery in the United States, Black women have been pushed toward caregiving roles for other children, and their work has been systematically underpaid and undervalued,” Liss continued.

In response to a request for comment, a spokesperson for the mayor’s office wrote, “Mayor Mamdani has been clear — the individuals providing these critical services must be paid fairly and equitably. We are committed to continuity for our 3-K and Pre-K providers and the families they serve.”

Low pay isn’t limited to teachers. Early childhood programs directors, who sometimes have decades of teaching and leadership experience, earn a median wage of $37 per hour, most without health insurance, according to a report by the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School. Assistant teachers typically earn well under $40,000 a year.

That has serious consequences for kids and parents, advocates and providers say. Programs struggle to hire staff, which results in empty classrooms and long waitlists. And when they do fill positions, teachers often leave as soon as public school jobs become available.

City funding for early childhood classrooms “doesn’t cover what the programs cost,” said Michelle Kindya, the co-director of Stepping Stones Pre-School. “Our liability insurance has doubled. Utilities go up. Everything has gone up except the budget.”

Kindya and her business partner, Marilynn Hopkins, have been running early education programs together for more than 40 years. They each have many years of teaching experience; Kindya was an early childhood professor at Brooklyn College for 11 years. And yet they earn less money than teachers with a few years of experience at public schools.

“We’re not valued,” Kindya said.

‘What would make them think we can survive?’

Like a lot of early childhood educators, Kindya and Hopkins say they stick with the job because they love what they do.

Five years ago, the city gave them a little bit of hope when a new round of contracts included a salary bump for pre-K teachers. There were no raises for directors or assistants, but Kindya and Hopkins figured they could hold out until the next contract negotiations. The system was finally moving in the right direction.

Then, at a meeting in November 2025, early childhood directors learned their contracts would be extended for two years with no funding increase — a decision made under former Mayor Eric Adams.

Meanwhile, Mamdani — who would soon take office — was promising a massive expansion of the system in which many programs were barely treading water.

“We were shocked,” Kindya said. “Before they spend the money to add 2-year-olds, shouldn’t they fix the programs they already have? What would make them think we can survive?”

The news galvanized many program directors, who decided to throw their weight behind a movement demanding pay equity for early childhood educators. They launched a letter-writing campaign to the mayor and a social media campaign to raise awareness. Much of the organizing happens over a group chat that uses a play on the acronym for New York City Early Education: “No more NYCEE.”

Early childhood classrooms will remain open during the Feb. 12 rally at City Hall, though some will rely on substitutes or alternate staffing.

“It will probably irritate people that we won’t be at work. We may lose pay, or PTO. It won’t be convenient,” one organizer wrote on a Facebook group for early educators. “THIS is our opportunity. SHOW UP PEOPLE.”

For Schneider-Kaplan, the tipping point came when she saw a series of social media posts showing Mamdani and Ms. Rachel, a YouTube star who makes videos for young children. One post was captioned, “If you’re excited for universal child care and you know it, clap your hands.”

Schneider-Kaplan responded with a post of her own, writing under the name ‘Ms. Becky’: “If you see every post about Universal Childcare as a slap in the face because you’re an underpaid and under insured teacher, clap your hands!”

Abigail Kramer is a reporter in New York City. Contact Abigail at akramer@chalkbeat.org.