When kindergarten teacher Alyxe Fields was a young student, she had trouble reading.

Decoding words was tough for her. Though she grew up to be a successful teacher at William Rowen School in West Oak Lane, the experience of struggling to read as a child has influenced how she approaches her 5-year-old students.

“It’s important for reading skills to be addressed early on so it doesn’t get passed over and then they just move on next year,” Fields said.

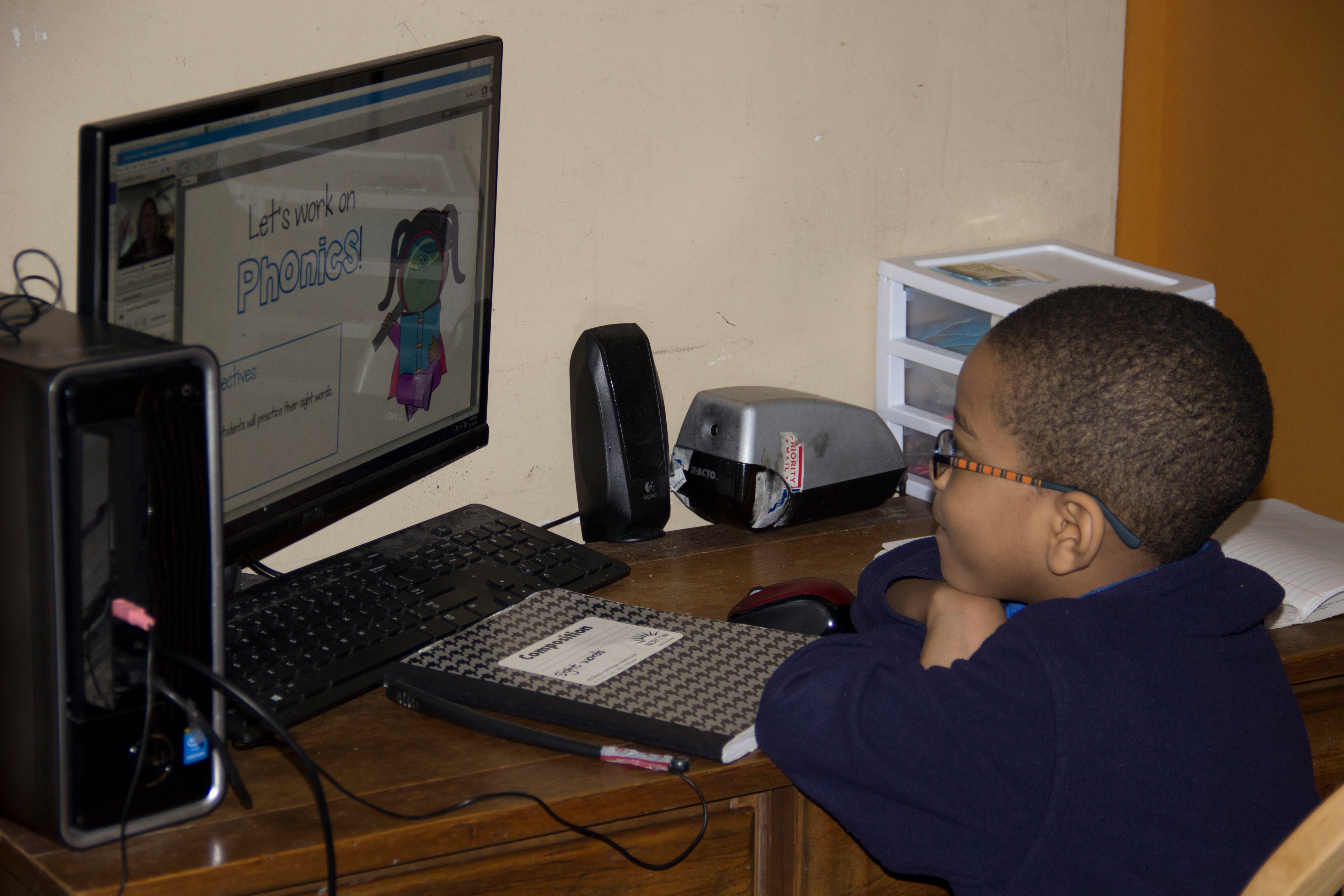

Remote learning has made a difficult task - teaching young children how to read - even harder.

As schools approach the one-year anniversary of the coronavirus pandemic, educators, parents and policymakers in Philadelphia are increasingly concerned about how the youngest students are learning to read. The shift to remote learning has exacerbated existing concerns in the city about early childhood literacy and the long-term effects on achievement.

Teachers and reading specialists report that students who regularly attend their virtual classes are indeed learning – a testament to both the remarkable ways teachers have been able to quickly adapt to their new teaching environment and the resilience of students – but educators fear that their students are not nearly as far along as they would have been in a normal school year.

“We are looking at significant regression in terms of students’ learning,” said Dawn Brookhart, associate director of the AIM Institute for Learning and Research in Conshohocken, which focuses on reading research and how to train teachers in evidence-based instruction through professional development and continuing education.

Literacy has been a longstanding concern in the Philadelphia school district. According to a district report presented at a Board of Education meeting in January, only 32% of third graders read on grade level. As part of its “goals and guardrails” initiative, the school board has taken up early literacy as a particular point of focus, aiming for 62% of students to be proficient in English language arts by 2026. In response to the report, Superintendent William Hite announced that the district would move away from a “balanced literacy” approach, which incorporates elements of whole language instruction, toward a model that is more focused on phonics and phonemic awareness.

Whole language instruction focuses on teaching reading by inferring information about a word from the larger context. Proponents of the “science of reading” point to research studies showing that children need direct instruction, with a particular focus on phonics, to learn how to decode words. Balanced literacy is an attempt to combine the two approaches.

Hite also said teachers need more long-term professional development for reading instruction. This is in line with advocates who argue many elementary teachers also aren’t trained in the science of reading. For them, sustained professional development is necessary so that teachers stay up to date on the research.

Brookhart said that many classrooms are still using a “broken model,” that uses strategies like the three cueing system where students are meant to draw information about a word from three contextual sources: visual (like an illustration), syntax (the role of the word in the sentence), and graphic (recognizing the letters themselves). Brookhart said that contrary to popular belief, learning to read is “not a natural process.”

“It’s not like language. It takes a very skilled practitioner to be able to understand how to truly teach reading,” she said.

Jen Lutz, a reading specialist at Community Partnership School in North Philadelphia, taught first grade before becoming a reading specialist. She said she was not armed with the knowledge she needed to most effectively reach students.

“Initially I didn’t really learn how to teach reading. I took one class and it showed me how to read picture books to kids,” she said.

It wasn’t until she earned her masters degree and a reading specialist certification — largely sparked by asking questions about why certain kids were learning to read while others weren’t — that she learned proven techniques.

While the mechanics of how we teach reading has been debated among researchers and educators for decades, the question has taken on new urgency for reading specialists, elementary school teachers, and school administrators alike during the pandemic. In many ways, the success of remote learning has been dependent on children’s individual situations – the ability to focus, whether they have a parent or guardian to help oversee school, the amount of distractions, inconsistent internet connection — so it’s likely that students in the same grade will come out of the pandemic with wildly varying reading levels.

For Lutz, the question has become about solutions: “Ok so what is going to be the most effective way to get kids back on track?” she said.

In that answer, she sees room for improvement beyond the pandemic. “The research is there. I think there is a lot of opportunity here for people to look at the way things were done and what can we do to accelerate how we fill in these gaps?”

Brookhart objects to the idea that this year of upheaval will lead to a generation of early learners with lower literacy outcomes. Instead, this may be an opportunity for the district to rethink how it teaches reading as it moves towards a more effective model.

“In all other industries, they’ve been forced to pivot, they’ve been forced to change. Unfortunately, education still, even as we look at schools that have gone back to in-person instruction, they’re still very much committed to that old traditional model.”

For Brookhart, Lutz, and a growing number of elementary teachers and reading specialists, a “new model” doesn’t necessarily mean shiny new hardware or buying fancy software. It means relying on and adopting the “science of reading” to guide which teaching techniques work best for the largest number of children.

Many reading specialists interviewed pointed to research that shows that while 40% of students will learn to read regardless of the kind of reading instruction they receive, the other 60% need a “structured literacy” approach. That means “explicit, systematic teaching that focuses on phonological awareness, word recognition, phonics and decoding, spelling, and syntax at the sentence and paragraph levels,” according to the Iowa Reading Research Center. These techniques have more often been used to target struggling students, but have been shown to be valuable and effective for all early readers.

At Rowen, where Fields teaches kindergarten, the school has been part of a partnership with Wilson Language Training to use the Wilson Fundations program, which is based on the kind of research that Brookhart and Lutz advocate using. The program originally developed strategies for students struggling to read, but has since developed a reading curriculum for the general classroom based on the same principles. Community Partnership School, the independent school targeting traditionally underserved communities in North Philadelphia where Lutz teaches, also uses Wilson Fundations.

Access to the program, which has been implemented at Rowen for a few years now, has been especially crucial during the pandemic, Fields said.

“I will sing the praises of the program in person — the way that they break down individual letters, letter sounds, and then the way that they slowly transition into blending them together,” she said.

But since the shift to virtual learning, it has become “our lifesaver,” giving teachers specific sequential lessons and materials that have been adapted for virtual learning including instructional videos, letter and sound flashcards, and tiles that students can use to build sounds, words, and eventually sentences.

Without it, Fields said, her students would be much farther behind.

Not all schools in Philadelphia have access to programs like these, virtually or even before the coronavirus. The pandemic has only thrown the need for more effective strategies to teach reading into even sharper focus.

Brookhart said teachers with the best of intentions try “a lot of interventions without really understanding what our students need.”

After the pandemic ends, schools across Philadelphia also may have to contend with teachers who are exhausted and demoralized from the extra work that comes with the remote teaching, shifting their pedagogy to react to a new virtual classroom experience, and ongoing stress about reopening.

Still, Brookhart sees the change already starting to happen. Throughout the pandemic she has seen an increase in the appetite for AIM’s evidence-based literacy course platforms and has been struck by the requests for more resources. “We are seeing now that more teachers and administrators are recognizing that they need to approach this differently,” she said.

The Institute also has a partnership with the Philadelphia school district to provide professional development and implementation, a relationship that Brookhart hopes will grow coming out of the pandemic, especially given the renewed emphasis the district is putting on early literacy.

“I think the opportunity is now for us to really reimagine education.”