Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

“Do you ever feel stuck? Like you can’t find the words? Or a heaviness that doesn’t go away? We do. And we’re trying to understand it and name it.”

The dialogue played from Craig Terry Jr.’s computer a few days ago, as he edited a video about grief during the holiday season.

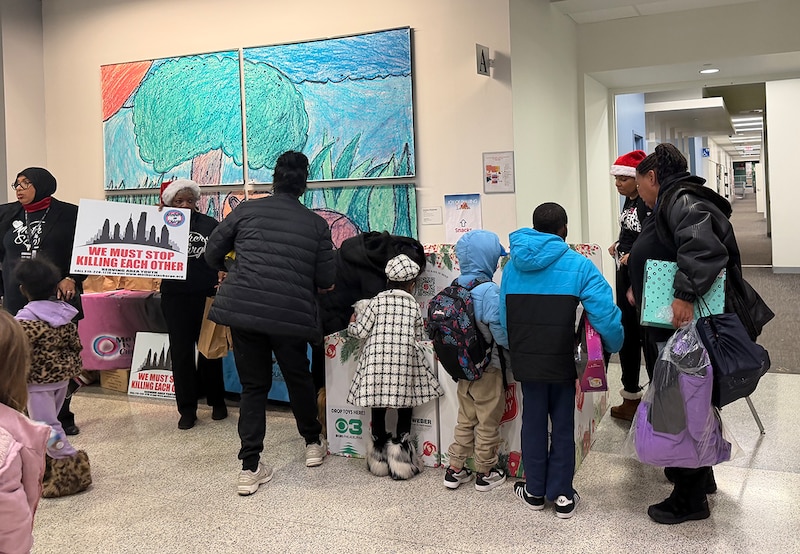

He and a cohort of young adults who are part of the Wealth + Work Futures Lab fellowship at Drexel University created the video. They showed the finished piece to students at YESPhilly Accelerated High School in North Philadelphia on Thursday. Their goal was to spark dialogue among young people who are grieving loved ones lost to fatal shootings and other causes.

The issue is personal for Terry Jr., who lost his cousin to gun violence in 2020.

“It is cold, we are with family, and there’s going to be a lot that will come up,” said Terry Jr., 26. “We need to build a space where people go into the holidays feeling prepared and aware of what’s impacting them.”

The alarming levels of homicide that plagued certain Philadelphia neighborhoods in recent years has left thousands of children grieving. While schools and nonprofit organizations offer support groups and art therapy, teens and those who serve them say children need more encouragement to find safe spaces to share their feelings.

Terry Jr. knows how hard it can be for kids to open up about grief, because he struggled to do so after his cousin’s death.

“I didn’t know how to engage with other people. It was just like, ‘this happens, and it’s been happening since I was a kid,’” he said. “So it wasn’t something that I found to be strange or something that I thought was going to impact me.”

That kind of desensitization is common among Philly kids impacted by gun violence, said Michelle Kerr-Spry with Mothers in Charge. It’s a violence prevention nonprofit created by Philly moms who’ve lost children to homicide.

“They accept this as just life,” she said. “They don’t realize this is not normal. It’s abnormal in the cruelest way possible.”

Kerr-Spry calls these children “the forgotten mourners.”

“They don’t always get the attention they need,” she said.

Grief support available in Philadelphia schools

In the School District of Philadelphia, grief support is provided by multiple outside organizations including the Uplift Center for Grieving Children, which runs groups in close to 100 schools, according to the organization’s spokesperson. Those groups can be tailored specifically to homicide depending on students’ needs.

In about eight other schools, similar services are offered by E.M.I.R. Healing Center, which has also provided crisis response in close to 20 schools in the immediate aftermath of a shooting, said the center’s clinical director Deshawnda Williams.

Around holiday time, they make a point of distributing flyers in person and posting resources and events on social media.

“The young people need to know how to navigate the system,” Williams said. “If you feel like you’re depressed, here’s some resources you can reach out to. You’re never alone. You don’t have to go through this alone.”

A few years ago, as Kameenah Bronzell was hearing about fatal shootings in Philadelphia, she decided to start an Instagram account memorializing those lost to gun violence and other deaths. It now has close to 48,000 followers.

“I feel like memories are really important,” she said. “And that’s all I do, is capture memories.”

Then in 2023, her own brother was shot and killed. She says she didn’t want to talk to anyone in the aftermath and felt “nothing but anger.”

Now 19, Bronzell said people in her life offered help after her brother’s death, but she didn’t accept it. Now she wants to help other school-age kids find support. Earlier this month, she spoke on a panel of people who’ve lost a sibling to gun violence.

“I feel like we have a lot of grief support and nonprofits that do stuff like that, It’s really just the kids that don’t want the help,” she said.

Parents also play a role in helping children in the wake of loss, said Williams.

“How do you show up when you lost one but you still have three? How do you show up as a parent?” she said. “We have services … that can support that adult so they can continue to be a first responder for a child that’s still here.”

In the fall of 2024, Mothers in Charge set up shop in a Dobbins High School classroom, where students could come during the school day to have a conversation with a trusted adult or fill out a workbook about their emotions.

“Young men who’ve been socialized their whole lives not to show emotion, they’re harder to reach,” Kerr-Spry said. “Then when they’re given the space … many do have a lot to say.”

The Philadelphia Board of Education approved new funding for the Dobbins program earlier this month.

How support can stop the cycle of violence

Grief services double as violence prevention, said youth mentor Kyron Ryals, whether or not they occur in schools. He helps oversee the Wealth + Work Futures Lab that Terry Jr. participates in.

“I’ve run into young people and it shows up as anger or destruction,” he said. “Sometimes they need time, and tools. When you ignore it, it’s still gonna show up.”

Terry Jr. said joining the fellowship helped him understand how losing his cousin was affecting him. He was withdrawn, anxious, and always looking over his shoulder, he said.

He eventually realized that suppressing his grief “has ripple effects on my overall emotional well being.’”

He and his cohort spent the beginning of this year interviewing 30 people in their age group about grief. They shared their findings at community events and published them in a zine.

Now they’re focused on getting the word out during the holidays through efforts like the video they showed to North Philadelphia high schoolers.

Terry Jr. wants to give children “a place where you’re not hurting other people, you’re not hurting yourself, but you have the safe space to grieve,” he said. “To be angry, to be happy, to be sad, to be able to wallow, to go through all the range of emotions and not feel like a burden.”

If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental health crisis, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing or texting “988.”

This story is part of a collaboration between Chalkbeat Philadelphia and The New York Times’s Headway Initiative, supported by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) via the Local Media Foundation.

Sammy Caiola covers solutions to gun violence in and around Philadelphia schools. Have ideas for her? Get in touch at scaiola@chalkbeat.org.