As Tennessee grapples with ongoing teacher shortages, the state Department of Education and the University of Tennessee system are opening a Grow Your Own Center to bolster the educator pipeline across the state.

The $20 million center will centralize and strengthen the state’s 65 existing “grow your own” programs, which seek to create new paths to the teaching profession by providing students with early teaching apprenticeship opportunities at no cost to them, state education officials and the UT system said during a Monday press conference at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

Retaining teachers is just one part of the solution to teacher shortages, said Penny Schwinn, the state commissioner of education. Tennessee wants to go one step further by building the workforce from the ground up, she said.

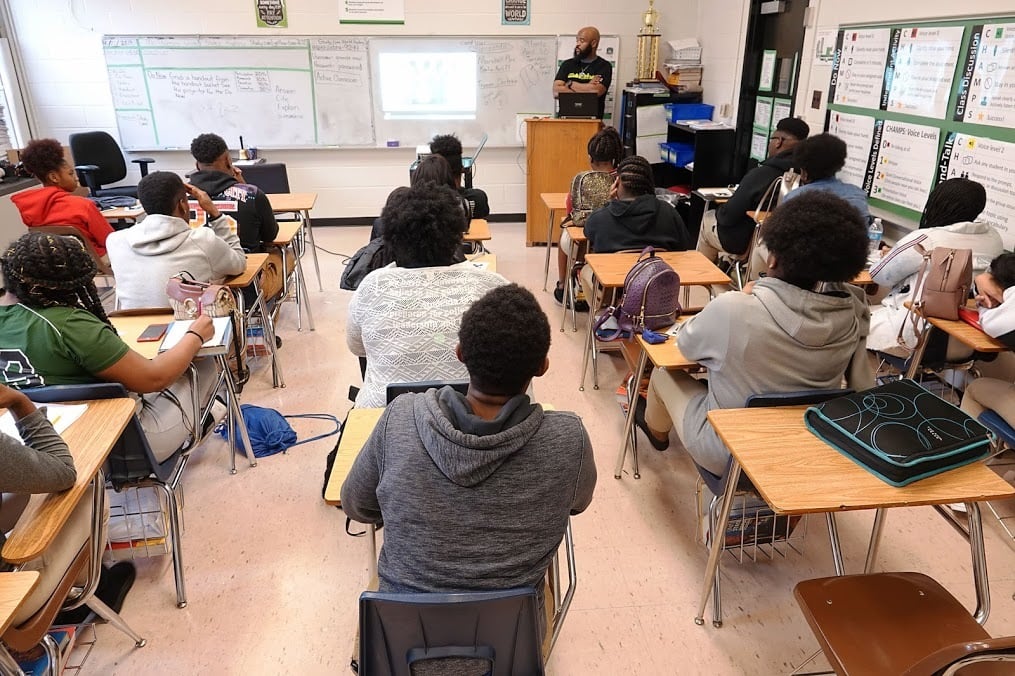

“The single most important thing we can do in public education is provide an excellent educator in front of every child, in every class, every single day,” Schwinn said.

To do that, she said, “we have to remove the barriers that prevent great people from becoming great teachers.” The apprenticeships supported by Tennessee’s Grow Your Own Center give future teachers “exceptional preparation at no cost,” Schwinn said, with thousands of hours of experience in the classroom alongside an experienced lead teacher who serves as a mentor.

While existing programs vary by district, they typically hire prospective teachers who work in school support roles and get paid while pursuing their education and credentials through a teacher training program.

The new Grow Your Own Center will serve several functions, state officials said, including serving as a technical assistance hub for local teacher apprenticeship models, helping develop and recruit candidates, and providing additional endorsements for teachers — like special education and English as a second language certifications.

Monday’s announcement comes four months after Tennessee announced a partnership with the U.S. Education and Labor departments to establish a permanent teacher apprenticeship program — the first state to do so. U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona has hailed Tennessee’s teacher recruitment efforts as “a model for states across the country.”

It also comes as the pandemic has put a spotlight on teacher shortages, caused by retention issues and the shrinking teacher pipeline across the nation. State and local public education employment fell by nearly 5% overall since the beginning of the pandemic — and by almost 7% among just K-12 teachers — according to a recent Economic Policy Institute report.

Last fall, 18 of 20 large U.S. school districts that provided data to Chalkbeat reported the number of teacher vacancies had increased this year.

Even before COVID, U.S. schools were struggling to fill open positions for over a decade: Between the 2008-09 and 2015-16 school years, the number of people graduating with education degrees decreased more than 15%, according to the report.

In Tennessee, the latest report card on the state’s 43 teacher training programs earlier this year found that the number of new educators graduating has dropped by nearly one-fifth over five years. At the time, state officials said Tennessee had about 2,200 teacher vacancies, though other estimates put the count significantly higher.

“We need to figure out a way to fix that,” said University of Tennessee system President Randy Boyd.

Samantha West is a reporter for Chalkbeat Tennessee, where she covers K-12 education in Memphis. Connect with Samantha at swest@chalkbeat.org.