Sign up for Chalkbeat Tennessee’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Memphis-Shelby County Schools and statewide education policy.

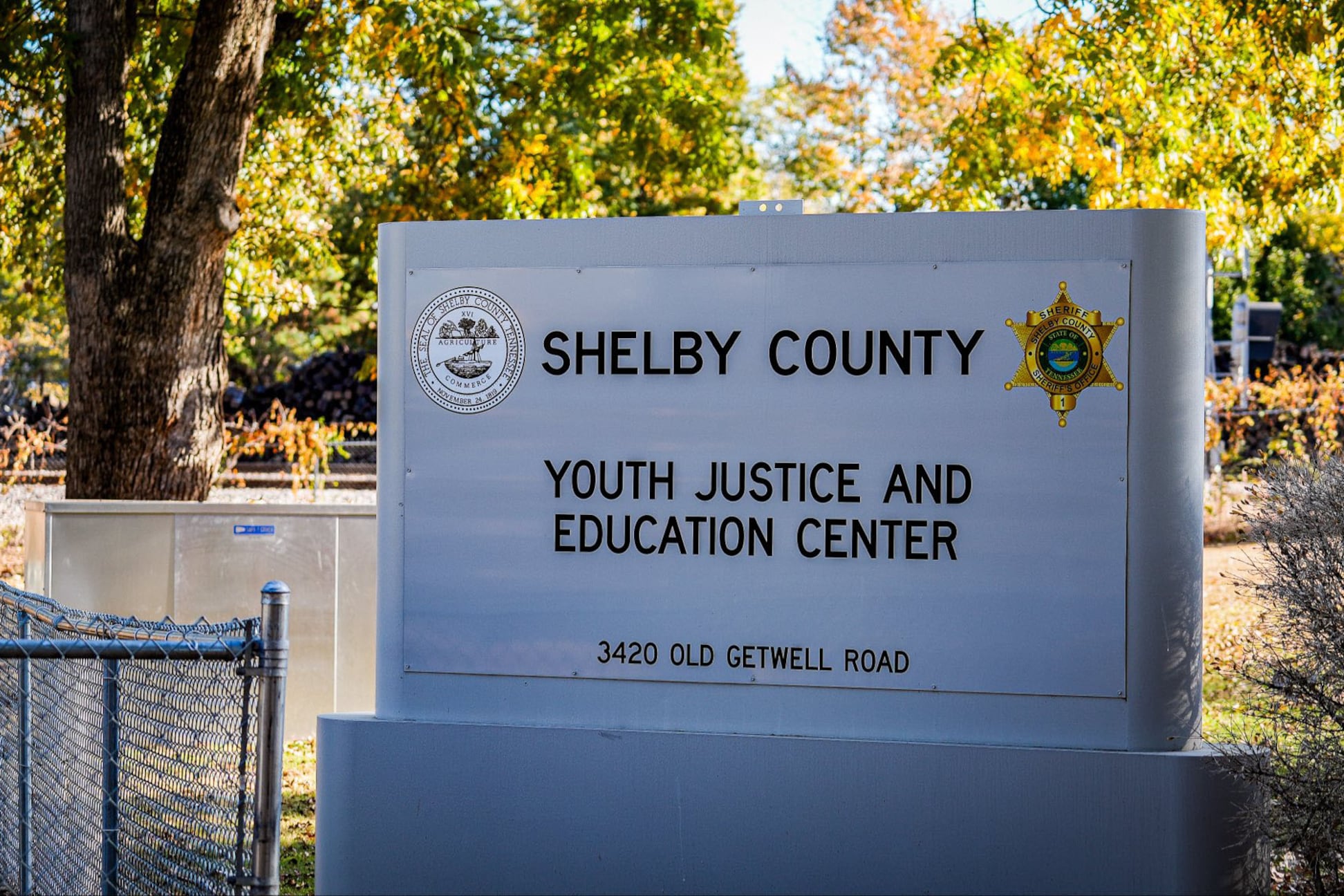

Shelby County officials are coming under fresh pressure to deal with education deficiencies in the juvenile-justice system, where advocates say not enough young people who are detained are regularly attending school or learning what they need to graduate.

A group of those advocates sent a letter this week to Shelby County Sheriff Floyd Bonner warning about the low rates of school attendance and demanding improved conditions for youth in detention beyond just their education.

The county’s Juvenile Court has known about the issues at the county’s Youth Justice and Education Center, and at the school inside, called Hope Academy. A consultant it worked with to identify issues facing youth in the facilities reported that just half of them were attending school each day, and that course offerings weren’t comprehensive enough to give students the classes they need to graduate, according to Stephanie Hill, the court’s chief administrative officer.

The findings were also shared with the Countywide Juvenile Justice Consortium last fall.

But the problems raised by the consultants, from BreakFree Education, can’t easily be solved without collaboration between the sheriff’s office, which oversees the detention center, and Memphis-Shelby County Schools, which operates the school.

Youth crime has been at the center of public discussion in Memphis and across Tennessee. Arrests of young people are down over the past decade, but more of them involve gun-related crimes that draw added law enforcement attention.

Meanwhile, detention facilities in Tennessee have faced intense scrutiny for failing to provide appropriate care to young people. In detention centers like Shelby County’s, where detainees have not yet been tried, missed school days put students who are already facing challenges outside of class at a greater disadvantage for long-term success.

Cardell Orrin, who leads Stand for Children Tennessee, one of the organizations that signed the letter, said part of the issue with improving youth attendance at school is knowing which agency to approach.

“Whose responsibility is it, and then how are they held accountable?” Orrin told Chalkbeat.

In a reply to the organizations, Juvenile Court Judge Tarik Sugarmon said that staffing issues at the facility have contributed to low school attendance rates of 50% to 60%, much lower than the court’s goal of 90%.

Bonner wrote in his own response that the 110 youth currently there were “far more than we had ever expected or planned for.” Instead, he said, 40 to 60 youth were expected to be in the facility.

Sugarmon called that “erroneous,” pointing out that the facility was newly built to accommodate some 140 youth. “It appears there are no physical facilities limits to school attendance,” he wrote.

The young people detained at the center are awaiting trial, and the number of students can vary day-to-day as trials progress.

Memphis-Shelby County Schools told Chalkbeat that it plans to keep working with the court and sheriff’s office to address concerns about Hope Academy. Marie Feagins, who took over as MSCS superintendent on Monday, toured the school last week, and said in a video interview that leaders should consider strengthening rehabilitative programs and expanding opportunities within the facility.

“When I think about education and the power thereof, it’s important to make sure that education, a quality education and experience, to the degree possible, is happening in all of our spaces and places,” she said, pledging to return often to speak with Hope Academy students.

Beyond the education issues, the advocacy groups said they wanted the sheriff to address complaints that youth aren’t allowed outdoors, and parents are being denied in-person visits with their children in detention.

They also said efforts to collect research that would improve programming for youth have been stymied by the sheriff’s office.

Shirley Bondon, the executive director of the Black Clergy Collaborative of Memphis, is hoping to conduct research with the youth at the facility to help improve their access to effective diversion programs, as an alternative to detention, and also get a better understanding of what youth need.

“Part of that research requires me to talk to youth in detention and have them complete a survey and get their perspective about why crime occurs, and what resources they need to keep them out of trouble,” Bondon told Chalkbeat.

“We need to scale those programs, and those programs need more funding,” she added. “We also found that the programs often aren’t evidence-based and don’t collect the correct data.”

Laura Testino covers Memphis-Shelby County Schools for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Reach Laura at LTestino@chalkbeat.org.