Allison Gorsuch, the mother of a Chicago kindergartner, made an impassioned appeal in front of the city’s school board this week: Spell out soon how the district will decide whether to bring students back to school buildings and when.

The decision on whether to bring students back into school buildings on Nov. 9 is looming for Chicago, the country’s third-largest district. During its Wednesday meeting, the district’s governing board largely focused on how remote learning has gone two and a half weeks in, offering positive reviews about what leaders feel was a strong start to the year. Board members did not broach the issue of how and when the district will make a call about the next quarter.

But on social media and in after-school meetups, parents have started wondering whether a return to in-person learning is still on the agenda. And on Twitter, the district’s teachers union has suggested the district is again eyeing a blend between in-person and remote learning — and has already strongly questioned whether officials can do it safely.

At Wednesday’s meeting, Jianan Shi, head of the parent advocacy group Raise Your Hand for Illinois Public Education, urged district leaders to include families in their decision making, noting seven weeks remain until the end of the current quarter. He said that remote learning is an imperfect scenario for many students and their parents but urged the district to proceed cautiously as it weighs shifting course.

“Let’s not rush into hybrid learning the same way we rushed into remote learning,” he said.

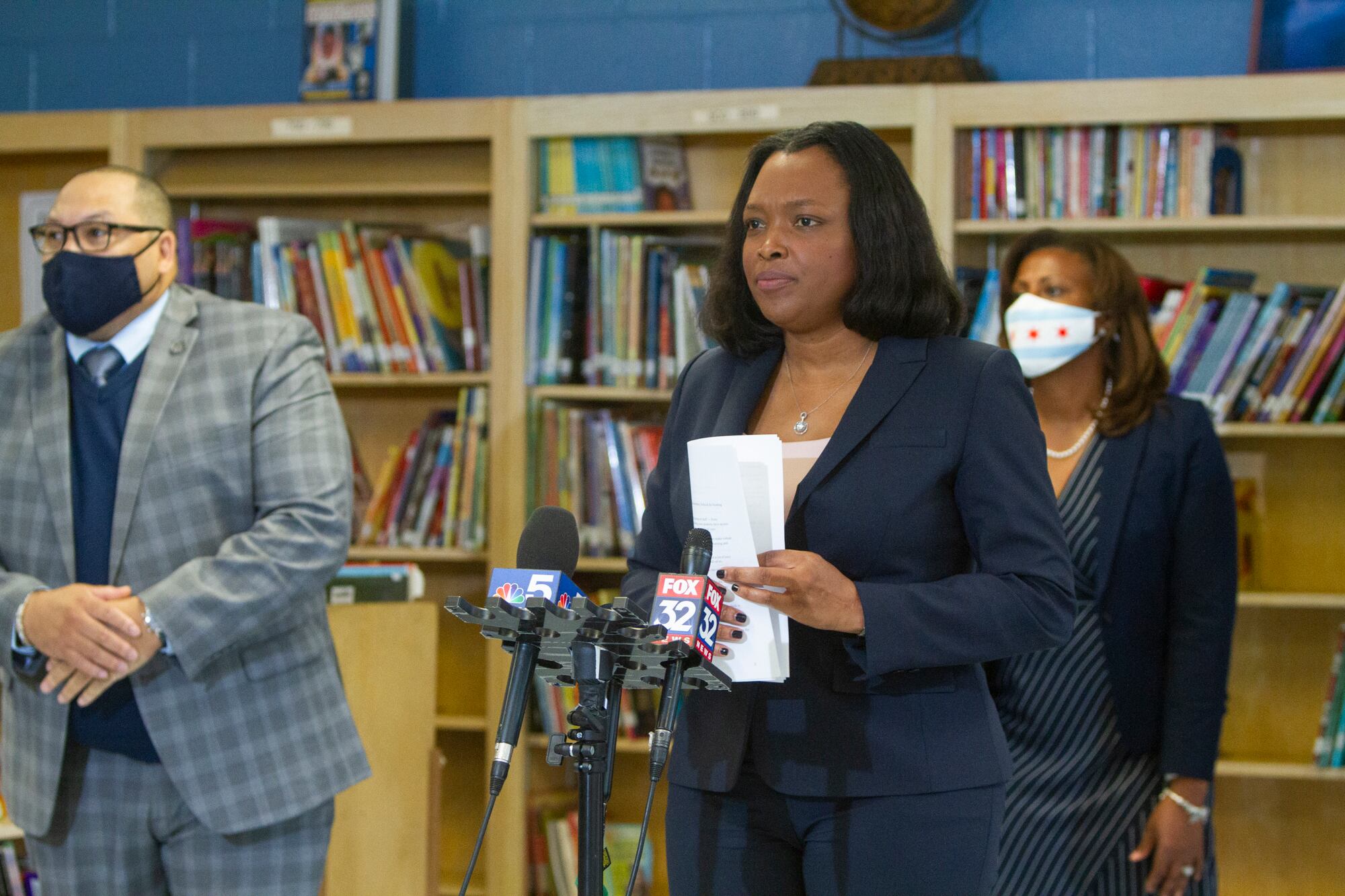

A district spokeswoman said after Wednesday’s meeting that the district will have more information about second quarter decision making at a later date. At an education townhall Thursday sponsored by the media outlet Politico, schools chief Janice Jackson praised teachers’ efforts to make the most out of remote learning. But she said plainly that children need to be in school buildings and the district still aspires to return them there.

“There are things that I think are critically important to child development that children are missing out on in a remote environment, which is why we are working extremely hard to get them back in school,” she said.

New York City was alone among the country’s largest school districts in starting the year with a hybrid approach including some in-person instruction. But last-minute changes of plans and miscommunication with families have made for a troubled start. This week, Miami-Dade, the fourth-largest district nationally, announced it plans to go back to full-time in-person learning next month. Meanwhile, some suburban Chicago parents have begun protesting and calling on their districts to reopen school buildings.

New York City’s last-minute switch could be a lesson for Chicago. Here, some parents have said a timely decision about the second quarter would help them plan and prepare.

Chicago district leaders had initially hoped to launch the school year with a blend of in-person and remote learning, with families having the option of choosing fully online learning. But amid an uptick of COVID-19 cases in the city, parent surveys that revealed safety concerns about in-person learning, and strong pushback from its teachers union, the district backed off from that plan. Officials said at the time that they would revisit the possibility of a partial return to school buildings during the second quarter — a decision they said they would base on the public health situation.

At the Wednesday meeting, board members spoke positively of the start of the school year in Chicago, congratulating district leaders and educators on what many of them felt was a smooth beginning marked by innovation and hard work.

“As a parent, I am hearing learning,” said Sendhil Revuluri, the board’s vice president. “I am also hearing joy.”

District leaders said they are encouraged by remote attendance numbers so far — LaTanya McDade, the chief education officer, touted a “strong start” to the year — but said the goal is to continue improving the quality of virtual learning.

“We are not spiking the ball at the 20-yard line,” said Jackson. “We still have a lot of work to do.”

But some parents urged the district to release its criteria for a return to school buildings as soon as possible — and spoke candidly of the challenges of learning online, especially for younger students. Gorsuch, the parent of a kindergartner at Pulaski International School, said her child and his teacher are working hard to make remote learning work. But for a 5 year old, the screen time is too much, and the time for crucial small group work and one-on-one support is not nearly enough, she said.

“I’m not asking for schools to reopen before it’s safe,” she said. “But I am asking that this not be a lost year for our youngest students.”

Another parent, Danielle Tobin, also said her family has been overwhelmed by the demands of remote learning, despite “ideal conditions:” students who have access to the technology they need and parents at home to supervise and guide them. She seconded the call for a head start on planning for the second quarter.

“The solution is to plan now and communicate to parents what the plan is,” she said.

Chicago has floated a plan to bring in some special education students earlier, but the union has balked, citing safety concerns.

Stacy Davis Gates, the union’s vice president, said district leaders have not yet tackled the issue of planning for the second quarter in weekly meetings they’ve held with the union, where the focus has been on improving virtual learning. She said it is time for the district to explain how it will approach the decision and address calls from the union for coronavirus testing and contact tracing protocols, which she said would be essential for a safe return.

“The difficulty I have at this point is that I don’t have a plan to react to,” she said. “You can’t say yes or no without any plan.”

She added, “It’s irresponsible and very magical thinking that we can treat a return to school idea flippantly. These questions are about life and death.”

In August, when officials were still backing a hybrid plan that involved some in-person learning, the district had said a daily average of 400 new COVID-19 cases over the course of a week would trigger an all-virtual learning approach, but they were watching other metrics closely. Scenarios such as a daily average of 200 cases coupled with a rapid increase in the rate of positive tests could also prompt a shift. It’s not clear if those metrics would still apply to the second quarter.

The city’s current daily average for the past week is 296 cases, with a positivity rate that has decreased slightly over last week.

The district’s original plan for fall had called for two days of in-person learning a week, with one day of live virtual instruction and two days of more independent learning. The district had said it would take a slew of measures to curb the spread of COVID-19: grouping students in pods of roughly 15 students with spaced-out assigned seating, requiring face masks and daily temperature checks, hiring 400 additional custodians to deep clean schools, and other steps. The district also said it bought 1.2 million reusable cloth masks for students and employees, 40,000 containers of disinfectant wipes for classrooms, and 22,000 touchless infrared thermometers.

The union had voiced skepticism that the district could ensure the safety of educators and students; it had raised the possibility of a strike over that earlier back-to-school plan. In a survey last summer, 40% of teachers who participated said school should not resume in person until a COVID-19 vaccine becomes widely available.

Some experts believe a vaccine approved for children might not become available until next fall, after an adult vaccine is adopted.

At the Thursday townhall, Jackson said she worries that remote learning is exacerbating longstanding inequities, with wealthier families creating learning pods and providing enrichment activities for students while some of their peers fall behind.

“I’m guilty of doing the same thing because I want to keep my kids engaged and I want them to be active,” she said. “There are far too many students who don’t have that privilege because they aren’t in school.”

Cassie Walker Burke contributed to this report.