Special education advocates are pressing the state to extend a deadline for Chicago families to seek relief for those years the district delayed or denied services to children with disabilities.

A bill in the state legislature, which would extend the timeline, passed a committee last week and will head to the House floor for debate.

The advocates say that the school district has reached out to only a fraction of families that it promised to contact, so they also are renewing a call to extend the length of time Chicago would remain under a state monitor for its years of failed service.

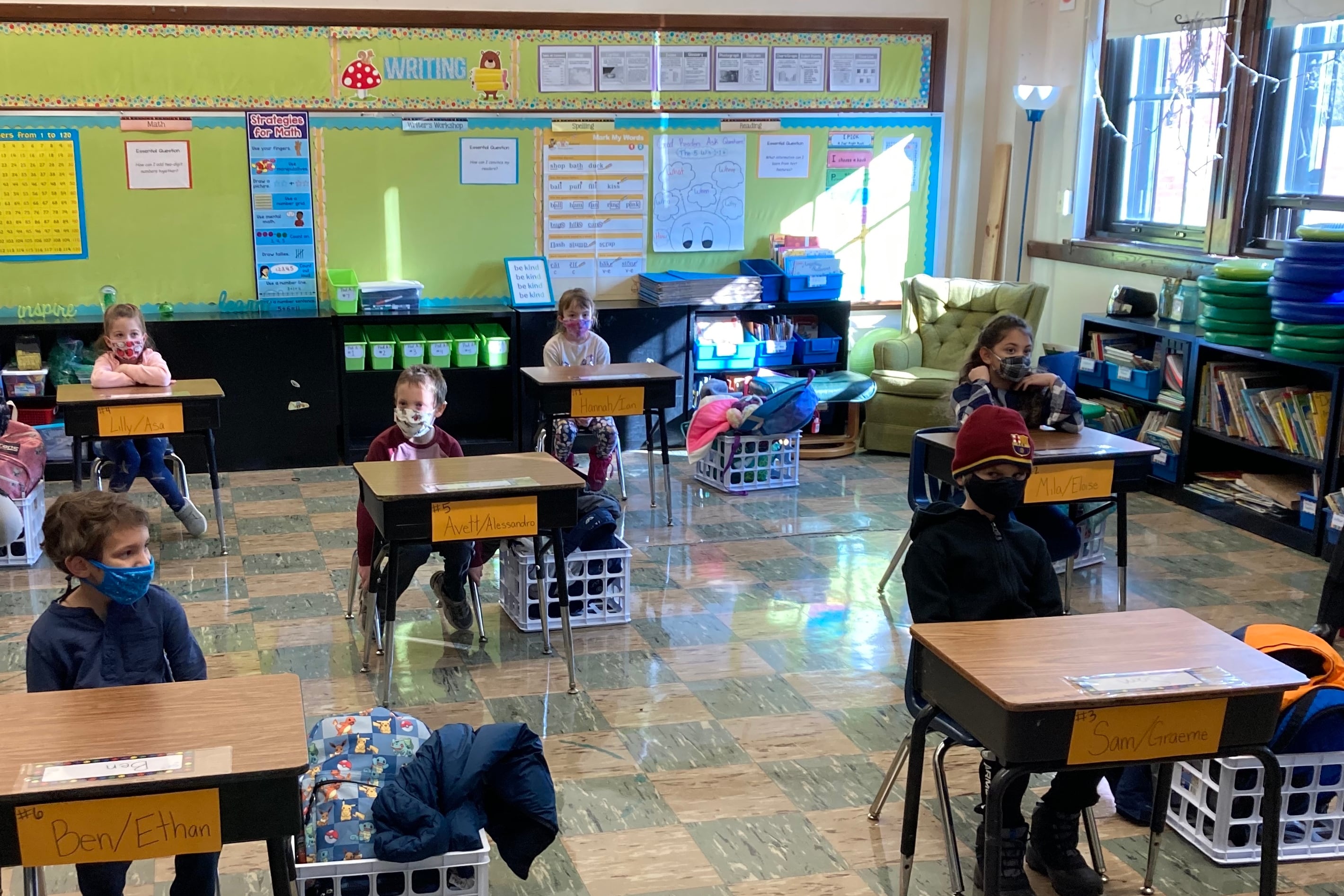

The pandemic, they warn, has made the situation worse for children with disabilities.

Special education advocates attended the House’s school curriculum and policies committee last week to testify in favor of HB 2425. This bill will extend the timeline for when Chicago families can file a complaint with the state board of education from Sept. 30 of this year to Sept. 30, 2022. The bill has received a lot of support, with 345 witness slips in favor of it.

An investigation by WEBZ in 2017 found that students with special needs were illegally denied special education services by Chicago Public Schools between the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 school years. As a result of the report, the state installed a monitor in the district in July of 2018 to identify students who lost services during those two school years and to create ways to help those students. The district has identified 10,000 who could receive funding for services lost, while over 1,000 students will receive services.

The issue also has surfaced at the state school board. Earlier this month, William Hrabe, an attorney at Equip for Equality, commented during the state board’s monthly meeting that Chicago said that it would make 10,500 phone calls and hold 1,300 meetings with families by the end September. So far, Chicago Public Schools confirmed that it has made 326 phone calls and held 235 meetings.

Hrabe called on the board to extend the monitor’s time in the district. “Many of these decisions will certainly take place after the minimum three year allotment for the monitoring position that expires later this year,” he said.

Barbara Cohen, a special education advocate with the Legal Council for Health Justice, testified to the house committee in support of the bill. In 2019, she and other special education advocates asked the state to extend the deadline for two years and now they are back to request another extension, she said.

“We thought everything would be fine now and that extending it for two years would be fine. The delays in rolling this program out have been so egregious just that there’s no way it’s going to be finished by September,” Cohen said.

The state board of education has given its support to the bill.

“Extending the deadline is deemed necessary to avoid the risk of a large surge of filings leading up to the current deadline of September 30, 2021. The anticipated surge in filings would risk overwhelming the system for investigating these complaints,” said Jaclyn Matthew, a spokeswoman for the state board of education.

However, state officials have not commented on whether they will extend the current monitor’s time or if they will place more monitors in the district to watch the process. The current monitor started in July 2018, and the state has said that it will determine the necessity of the monitor after three school years.

The bill passed unanimously out of the House’s committee.

Correction: An earlier version of this story had a different first name for William Hrabe, an attorney at Equip for Equality,