As the coronavirus pandemic uprooted schools for millions of students across Illinois, the state board of education was tasked with churning out new guidance for the state’s 852 school districts. Leading the board was Darren Reisberg, who started working at the board in 2005 and was later appointed by Gov. J.B. Pritzker in 2019 to serve as chair.

Now Reisberg is leaving the state board and his position as executive vice president and chief strategy officer of the Joyce Foundation (a funder of Chalkbeat) to become the 11th president of Hartwick College, a small liberal arts college in New York. His last board meeting will take place on June 15.

“I am incredibly excited about my next journey,” said Reisberg. “Small liberal arts colleges have to find a way to distinguish themselves in order to attract students. I think Hartwick has done a nice job in terms of figuring that out. I’m going to be there to try to take it to the next level —it’s a big challenge for me and I’m ready to do it.

Chalkbeat Chicago sat down with Reisberg to talk about chairing the state board during the time of the coronavirus pandemic, efforts made by the state board during the last couple of years, and what he hopes for the state’s future.

This story has been edited for clarity and brevity.

What led you to a career in education?

Once I started at a law firm, it allowed me to become part of the civic community in Chicago. I was able to connect with Chicago Public Schools as a volunteer. After about five years into my time at the law firm, I had that urge to do more but I didn’t know what that might look like. Coincidentally, there was a position that opened at the Illinois state board of education as deputy general counsel. That’s what brought me into working at the board of education in 2005. I ended up becoming general counsel, I developed a strong relationship with the state superintendent and became deputy superintendent in addition to general counsel and worked on education policy.

Pick one word to describe working at the state board during the coronavirus pandemic.

Exhausting. No matter how much we tried to focus on education policy over the course of the past two years, the public health crisis and other issues were all-consuming. We weren’t able to focus on our strategic plan in the way that we wanted to.

With everything the state was juggling at the time, what were some efforts that were sidelined?

While it didn’t fall by the wayside — there was a lot of attention on this issue — improving our assessment system was one of those efforts. Carmen Ayala, state superintendent, really spent time trying to build out some potential options to see how we can improve. One of the efforts was to develop a through-year assessment to replace our current summative assessment system. That was in large part because of concerns about the assessment system in Illinois; that it doesn’t provide actionable results for purposes of instruction, it’s too long, it takes too many days away from instruction, and it takes too long to get the results back. All of these issues, Dr. Ayala has tried to address but due to pandemic, it has just taken a long time to be able to actually get the stakeholder engagement. By the time we get feedback, I think the four years of our respective terms are going to be up. I think the question is, what is the next step? My hope is that the next board is able to lead on that and that we’ve set up the table for them to do that well.

Any efforts that ISBE was able to do during the pandemic that you were proud of?

Prior to the pandemic and during the pandemic, I am proud of our equity work. I was able to chair a task force with a high school student to create a resource guide for school districts to better understand the many issues that trans and nonbinary students face and provided the students and their families and advocacy groups with really important information to help improve the lives of students in the state. That’s a real tangible action that I’m super proud of on a personal level as being part of the LGBTQ community.

At a time when you’re seeing the critical race theory issues pervading across the country, the state board was able to push for culturally responsive teaching and leading standards here in Illinois. That will guide the way educator preparation programs prepare educators to go into classrooms. Even though we had a minority of stakeholders pushing against us, we didn’t back down.

What was inspiring to you during this time?

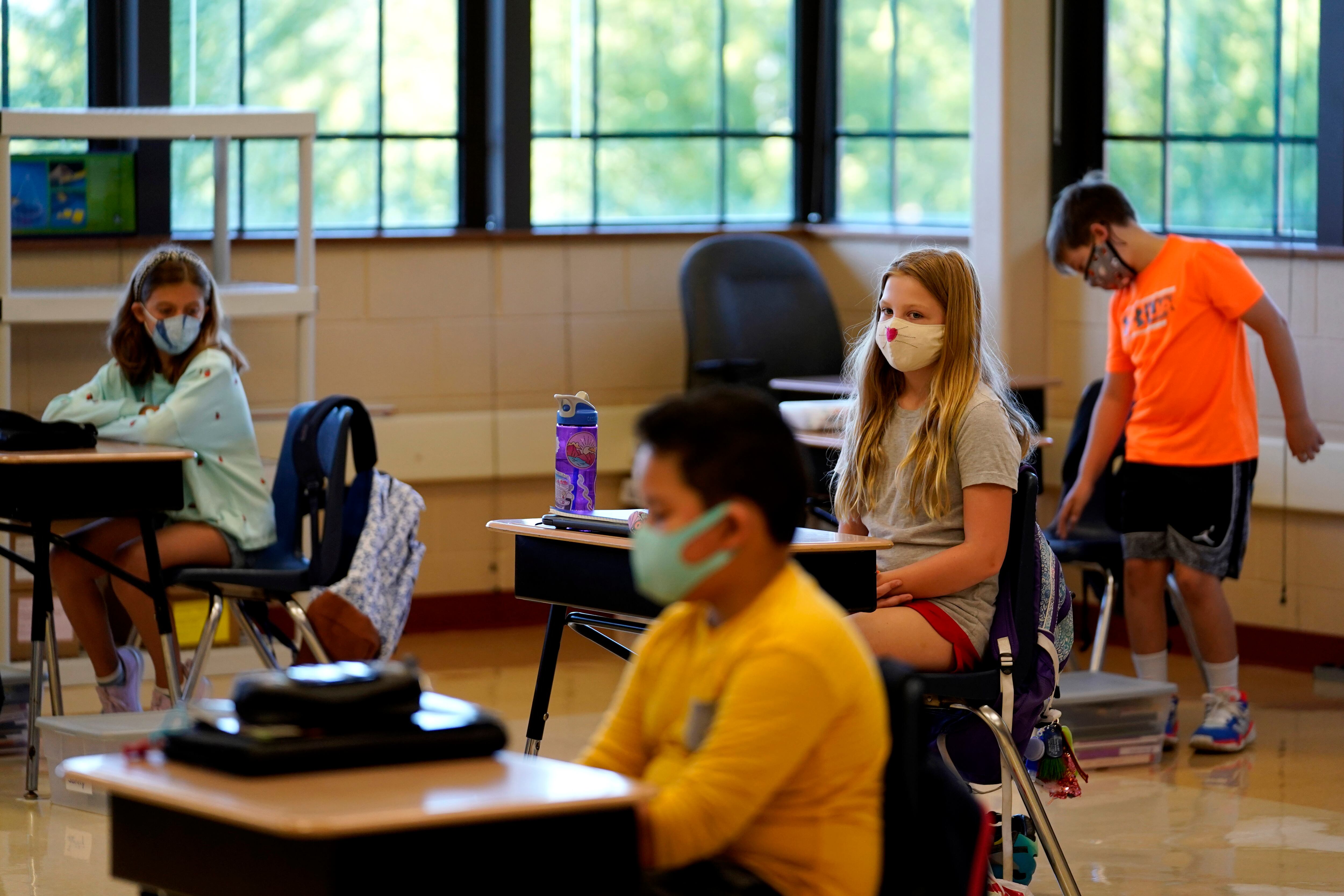

What was inspiring was seeing 852 school districts with superintendents, principals, teachers, parents and students push through it. Our kids —whether it was remote learning or ultimately back in the classroom — were still given opportunities, despite all the headwinds that made that super difficult. When I say it was exhausting for us at the state board, I know it was even more exhausting for those who were on the ground. That was extremely inspiring for all of us.

Are there any efforts that the state should be looking at to continue to get schools back on track?

My hope is that some of the ways in which the state board is using our state set-aside funds from ESSER are designed to do that very thing. Thinking about virtual induction and mentoring programs for educators across the state to make sure that we’re seeing meaningful retention of our teachers. So that you have continuity within our schools and that we’re not exacerbating the shortage. Thinking about how the rollout of the high-impact tutoring that is happening across the state can play out, so that we’re doing what we can. For school districts that don’t have the resources or the expertise, to be utilizing formative or interim assessments to be able to more quickly get a sense of where students are and to help guide instruction for those students as recovery continues. Those are ways that we’re trying to utilize these resources and what I think is really critical is trying to understand where those investments are actually making a difference.

Any advice for the next board chair?

Spend time meeting with key stakeholders in the field to be able to learn what is on everybody’s mind. These past couple of years have been so unique, that you just need to really understand where everybody is coming from in order to make good policy. It’s a lot waiting at the front end in order to be informed enough to be making good decisions.

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago, covering school districts across the state, legislation, special education, and the state board of education. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org.