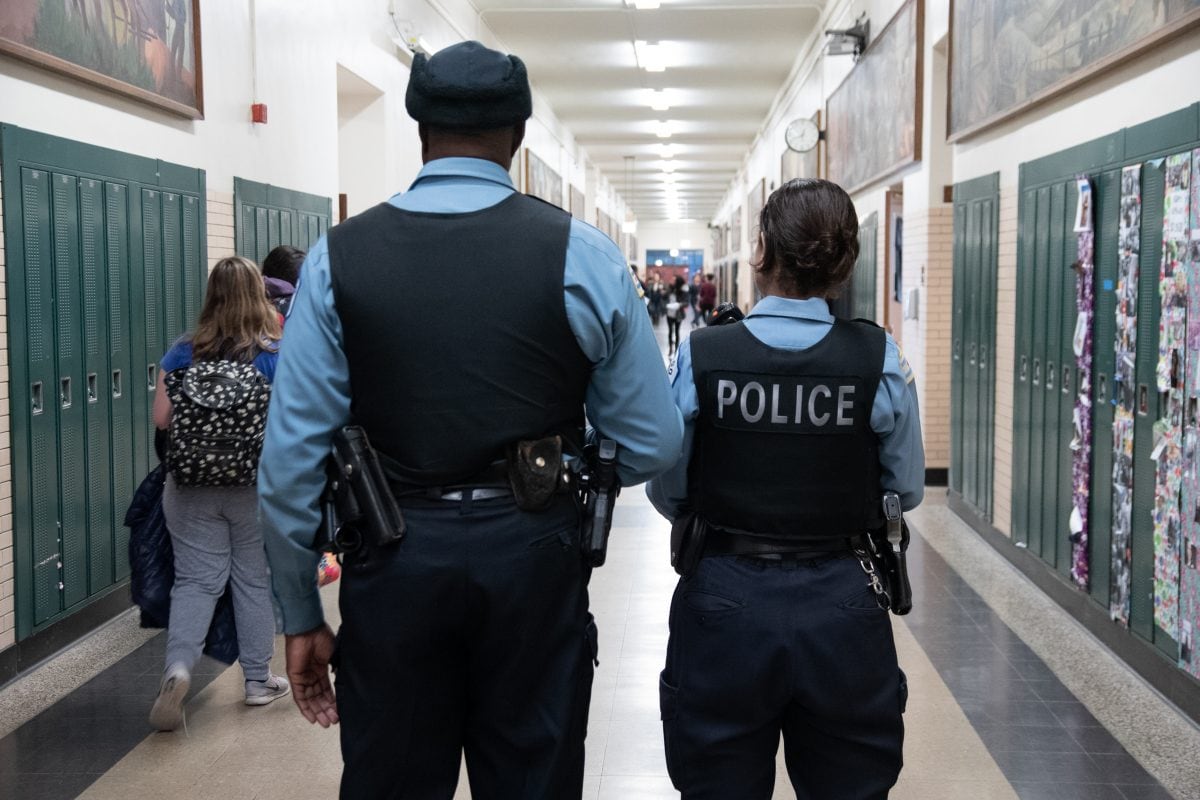

Chicago Public Schools will spend $10.2 million to station police officers at 40 campuses starting this fall — an $800,000 decrease from the previous school year.

The new contract, approved by a 5-1 vote at Wednesday’s school board meeting, will cover salaries and benefits for 59 police officers at campuses primarily on the South and West Sides for the 2022-23 school year. The decision comes as dozens of campuses have voted in recent years to shift funds away from punitive discipline measures and toward more restorative practices, such as healing circles and alternative interventions.

Chief Safety and Security Officer Jadine Chou said the district has been working to change its approach to safety since the summer of 2020.

The new Whole School Comprehensive Safety Plan was developed in partnership with five community groups, including Mikva Challenge and COFI, to empower school communities to make the decision of retaining or removing officers, Chou said.

Under the new contract, principals will have the right to reject police officers who are applying for positions in schools. The police officers selected must undergo training that includes restorative practices. Police officers will not be allowed to intervene in school disciplinary actions.

Board member Elizabeth Todd-Breland, who voted against the contract, said schools shouldn’t have police officers because of evidence that the presence of SROs leads to disproportionate criminalization of Black students and students with disabilities.

Todd-Breland lauded Chou for making progress with fewer officers in schools, but noted most of the schools that have kept police officers are majority Black schools.

“This is upsetting, right?” Todd-Breland said. “This is also, in ways, a symptom of the fact that we deferred this decision-making to the school level.”

In 2020, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers prompted a nationwide conversation about removing police officers from schools. In Chicago, some students, parents, and activists called for the removal of officers from schools and for shifting those resources to mental health and restorative practices.

Of the 41 schools that revisited their votes this spring, most schools have voted to keep the status quo, Chou said.

The following schools voted to keep one of two police officers: Air Force, Hyde Park, Julian, Lindbloom, Little Village, Marshall, North-Grand, Orr, Richards, Tilden, Wells, Westinghouse, Farragut, Gage Park, Hirsch, Hubbard, Englewood STEM, Douglass, Crane Medical, CSIS-Ellison, Chicago Military, Carver Military, and Dyett.

The following schools voted to keep both officers: Austin CCA, Harlan, Bogan, Kenwood, Manley, Bowen, Morgan Park, Chicago Vocational, Corliss, Collins, Simeon, Steinmetz, Young, Fenger, and Foreman. Taft, which has two campuses, voted to keep both resource officers at each school.

Dunbar High School voted to remove both officers.

Schools that removed police officers can spend the money toward safety measures on campus, Chou added.

Last year, about $3.8 million was invested to pay for staff, programs, and professional development related to safety at schools that voted to remove one or both officers, according to the district.

The district has reduced its spending on police officers by a third from $33 million in 2019-2020 to $11 million last year.

Mauricio Peña is a reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago, covering K-12 schools. Contact Mauricio at mpena@chalkbeat.org.

Eileen Pomeroy is a reporting intern for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Eileen at epomeroy@chalkbeat.org.