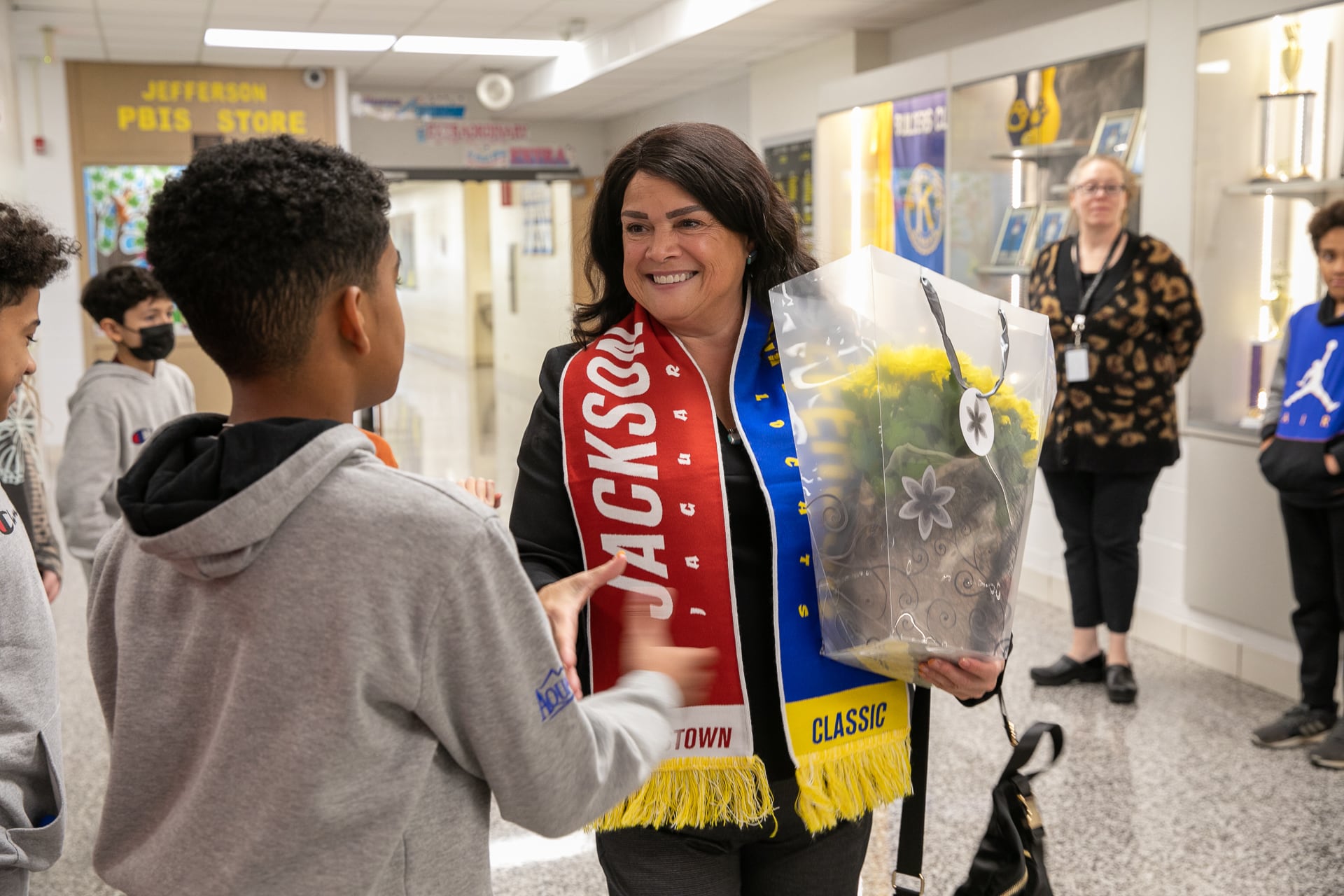

State Superintendent Carmen Ayala was one of the key players helping guide Illinois’ 852 school districts during the pandemic. Now, she is retiring after 40 years in education, and just as schools are starting to recover from the fallout of COVID-19.

Just one year after being named superintendent, Ayala found herself standing next to Gov. J.B. Pritzker as he announced the closing of over 3,000 schools to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. With Ayala at the helm, the State Board of Education quickly responded to the pandemic.

Now, with schools reopened, classrooms buzzing with activity, and districts flush with federal dollars to help schools deal with the fallout from the pandemic, Ayala said she feels that “It’s time to rest.”

“I’m excited in a way, because I am going to be able to do more yoga, take golf and singing lessons, and enjoy my children,” said Ayala. “It’s a little bittersweet, because the agency is at a certain point right now and there are so many exciting things coming down the pike.”

Ayala spoke with Chalkbeat about her time in office during the pandemic and what’s next for the Illinois State Board of Education.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

When schools shuttered in March 2020 to prevent the spread of COVID-19, what were you feeling?

The pandemic was very difficult on everyone at all levels. At the classroom level, with teachers and students trying to pivot to remote learning. At the school level, trying to organize everything that is needed like buses and delivering food to children. District level board meetings were quite contentious, because there were differences in opinions. Then at the state level, we worked very closely with the state’s Department of Public Health and relied on their expertise. We wanted to make sure that the decisions we made to keep people safe and save their lives was based on data and science.

What were your concerns for the state’s almost 2 million students at the time?

We were dealing with a pandemic where hundreds of thousands of people lost their lives, so I was worried about students’ safety and well-being. Remote learning was another concern. Our most vulnerable children — low-income children, children of color, children living in poverty and children with disabilities — were negatively impacted by remote learning. Also, I was concerned about students’ mental health, because they were not able to engage with peers and have social activities.

What would you say is the biggest unfinished business from your time in office?

One of the biggest things that is unfinished, but on the right road, is recovery. We’re not where we need to be in terms of health, wellness, and academics. We have to keep pushing forward and supporting our students. We have some great things available, like the six social-emotional hubs across the state providing trauma-informed services and supporting partnerships between schools, health professionals, and counselors.

What efforts are you most proud of over the past four years?

I am very proud of the equity work that the agency has done over these last four years. Our strategic plan has an equity statement and goals that really permeate throughout the plan. The equity journey continuum is now posted on every district’s report card, and provides the community and district with information about how they are doing. That’s important because of the 852 unique districts that we have across the state. At the State Board of Education, we’ve developed, implemented, and are working with an equity impact analysis tool. All of the decisions and activities that we do are filtered through an equity lens.

As school districts work to deal with educator shortages and diversify the teacher workforce, what efforts will the state need to continue or create to improve the situation?

We still have a teacher shortage that impacts specific areas like early childhood, special education, bilingual education, and in rural areas. To help get more teachers in certain fields, we started the career and technical education pathways where you provide grants and give designation on students’ diplomas that they have completed a particular pathway. This program provides students with dual credit and early teaching experiences to help them move on towards getting a teacher license. We’re preparing for potentially more than 10,000 teachers across Illinois.

What do you think is the best way to assess students for learning loss? What should the state do next?

Federally, we’re required to have a summative type of an assessment that is directly aligned to our Illinois Learning Standards. It can’t be an assessment that we just simply buy off the shelf. We have a state assessment review committee that is advisory and makes recommendations. We had one of the most robust stakeholder feedback engagements that we’ve had in quite some time and got great feedback. The state’s assessment review committee has provided the beginnings of a roadmap to guide us throughout our next steps. One of those steps is being clear on what is the true role, function, and purpose of our required Illinois assessments.

Students with disabilities struggled to get services written in their individualized education plans throughout the pandemic. What do you think went wrong and could have gone better? What would you say to families who did not get what they needed?

It was difficult to provide services that required face-to-face interaction. Some services could not be provided through Zoom. That’s one of the major reasons probably why some of the services were not able to be provided. Once we were able to come back to school, schools were trying to meet the requirements of the students’ individual education plans. We also experienced some loss in staffing due to the pandemic. But I hope that students are getting the services that they need.

What is your advice for the next state superintendent?

My advice to the next state superintendent is to communicate. It’s important to the field that they are aware and have information about what may be coming down the pipe. Also, communication is two-way street, providing information but also seeking and listening. The field will let you know where their greatest struggles are and where their greatest needs are.

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago covering school districts across the state, legislation, special education, and the State Board of Education. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org.