Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

As they worked to close a budget deficit this summer, Chicago Public Schools officials proposed a surprising and bold cost-saving measure: Combine the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund with the Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System.

Chicago school officials said the move could direct more money to schools by reducing the cost of Chicago’s contribution to the pension fund. It would also mean Chicago taxpayers would no longer have to pay for two pension funds. As Illinois residents, Chicagoans contribute to the state teacher pension system for districts outside Chicago, and they also pay for Chicago teacher pensions through their property tax dollars.

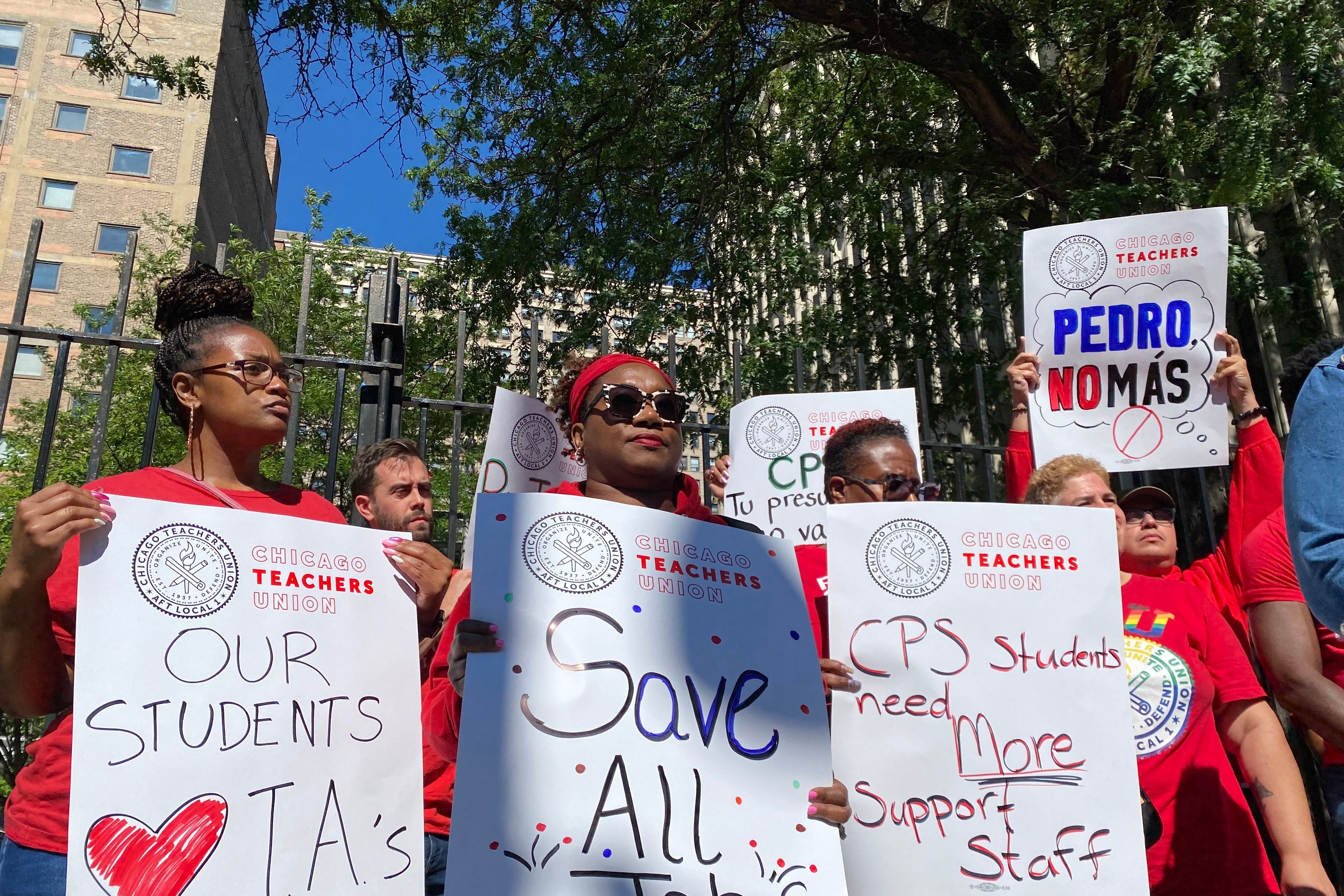

Both the Chicago Teachers Union and the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund oppose the plan, saying teachers would not support it and both groups want to keep the pension system they’ve had since 1895.

The Illinois General Assembly would have to pass a bill for a consolidation of both pension systems to happen. Even proponents of the plan aren’t sure if state lawmakers would take this on.

Chicago Public Schools pays for the pension plan out of its operating budget each year. This school year, Chicago’s budget projects paying $661.6 million toward teacher pensions. This number includes $102.9 million from the district’s operating budget, $558.7 million from property taxes, and $353.9 million from the state.

That sizable payment comes as Chicago grapples with the loss of federal COVID relief funding, a decrease in property tax revenue, the increased cost of employee health care, and an uptick in expenses for students with disabilities. In addition, it’s unclear how much teacher salaries will increase over the years as contract negotiations are ongoing.

Why is Chicago proposing consolidation now?

Chicago Public Schools’ proposal, first raised by Kids First Chicago and The Civic Federation, would require the state to take on the current costs of teacher pensions and previous debt by combining both pension funds. Kids First Chicago and the Civic Federation say a consolidation could solve Chicago’s budget deficit and bring “parity” to how teacher pensions are funded in the state.

In a statement to Chalkbeat Chicago, district officials said the district makes

“substantial payments toward teachers’ pensions” while the state pays about 25%-30% of CPS yearly pension system. Chicago Public Schools says the state government pays the cost of teacher pensions for other Illinois school districts. Chicago hopes consolidation would put more money toward schools at a time when they are having financial struggles.

“As a district, we have been making historic strides in academic recovery that show our school investments have been working, leading us to advocate for more equity in state funding to ensure we can continue to support teaching and learning in the State’s largest Pre-K-12 school district,” the statement said.

The story behind why Chicago Public Schools have to contribute a large amount of district funds starts in 1995. That year, the state passed the Chicago School Reform Amendatory Act, which gave Chicago’s mayor control over the school system and to send property tax revenue to Chicago Public Schools’ operating budget instead of directly to the pension fund.

In 1997, the state legislature passed a subsequent law that allowed Chicago Public Schools to stop making payments to the teachers’ pension fund if it had almost 90% of the money to pay out teachers’ retirement benefits.

Under former CPS CEO Paul Vallas, the Chicago Board of Education redirected property tax revenue to the district’s overall operating budget to deal with an anticipated $1.4 billion budget deficit in 1995. The Board of Education did not pay into the teacher pension fund until the early 2000s.

Between 1998 and 2003, the fund had almost 90% of the money needed to pay out teacher retirement benefits. But when the stock market crashed in 2008, investment assets and pension systems across the country, including the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund, took a hit.

As of 2023, the fund has slightly less than half of the money needed to pay off teacher pensions.

Carlton Lenoir Sr., executive director of the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund, said the organization found that $3.2 billion in contributions were not made to the pension fund after state laws changed in the 1990s and the district stopped making payments. No matter the investment returns, he said, the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund could not make up for the lack of funding.

“It wasn’t something that we could invest our way out of because the funds were just not there to invest,” said Lenoir.

Proponents doubt state would pick up the bill

Consolidating the plans would require state lawmakers to pass a bill to combine both pension plans – something proponents of the proposal think is unlikely.

Kids First Chicago, a nonprofit that organizes Chicago parents, and The Civic Federation, a nonpartisan research group, say state lawmakers might not want to consolidate both pension systems because the state would have to allocate more funding to cover Chicago’s debt.

Both organizations propose gradual consolidation of both pension funds over the course of 10 years to make the proposal more palatable for legislators to create and pass a bill on.

Hal Woods, chief of policy for Kids First Chicago, said if the state were to consolidate the teacher pension funds over a year, it would cost the state about $650 million. But if the General Assembly were to do it over 10 years, it could be easier to get through Springfield.

“The state with a $50 billion budget could actually absorb those new costs,” said Woods.

A report from Kids First Chicago notes there is still concern about the future of consolidation. The report, which was issued in July, notes, “future state administrations or economic downturns could alter the commitment to this funding arrangement.”

Chicago teachers don’t want to get rid of their pension system

Another major obstacle to consolidating both pension systems will be gaining the support of current educators and retirees.

After Chicago officials proposed consolidating the funds during contract negotiations with the union, the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund’s Board of Trustees said it did not support a consolidation, according to Lenoir, the Chicago Teachers’ Fund executive director. Even if the board was to support the proposal, retired and current teachers would have to vote for consolidation and Lenoir believes the plan would not have any support.

Also, Lenoir said the fund is in a better position than the state’s and Chicago educators would not support a consolidation.

The Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund is currently 47.2% funded, while the state’s is funded at 44.8%, Lenoir said.

The Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund has 10 elected representatives and two appointed by Chicago Public Schools on the Board of Trustees, while the state has a board of 15 members with seven elected members. Lenoir says the fund worries consolidation means Chicago teachers would lose a seat at the table to determine what business the fund invests in. The fund is currently invested in minority and women-owned businesses.

The Chicago Teachers Union, which has come out against the proposal, acknowledges it is “unfair and inequitable” that Chicago taxpayers have to pay into both teacher funds.

However, the union said, “Instead of risky consolidations, CPS should fight for the state to properly fund the [Chicago Teacher Pension Fund] just as it does for downstate teachers.”

Samantha Smylie is the state education reporter for Chalkbeat Chicago covering school districts across the state, legislation, special education and the state board of education. Contact Samantha at ssmylie@chalkbeat.org.