Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest news on Chicago Public Schools.

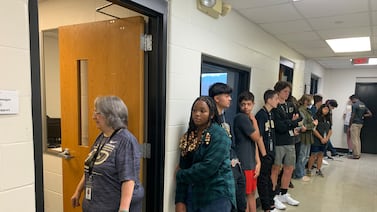

Outside the Acero Santiago charter school campus in Chicago’s West Town neighborhood, Principal Melissa Sweazy greeted students and parents as if they were celebrities.

Under a sunny sky and one of the mildest mornings the city has seen all summer, Sweazy cheered and waved glittery maroon and gold pompoms as the kids, dressed in white shirts and navy blue pants or skirts, walked down a paper red carpet into the big brick building.

“Vivir Mi Vida” by Marc Anthony blasted out of a portable speaker perched in a planter near the entrance. “I missed you,” Sweazy said to one young student who hopped toward the front door. “Buenos dias, mi amor,” she called to another.

A mother asked Sweazy what was going on at the other end of the school.

“We’re just trying to make sure CPS buys our building,” the principal replied.

On the east side of the building, in sharp contrast to the first-day hugs and hellos, the scene was somber. Two elected officials hosted a press conference, surrounded by dozens of teachers, students and parents who held signs that said, “Save our school,” and “Not For SALE.”

Santiago and four other Acero campuses narrowly avoided closure this year, when the Chicago Board of Education took an unprecedented vote to save the campuses in February and turn them into district schools by the 2026-27 school year. Now, the school is facing a new obstacle: The Archdiocese of Chicago, which owns the school building, put it up for sale last month for $6.75 million, according to elected officials and a Zillow listing.

“The Santiago community is once again – once again – facing another threat of closure,” Ald. Gilbert Villegas, flanked by school board member Carlos Rivas, told reporters. “It caught many folks off guard.”

The split-screen action reflected a small, tight-knit school celebrating another year of existence, while grappling with a potential sale that the community worries could end with their building being razed by a developer.

In a statement, Yasmin Quiroz, communications and public relations manager for the Archdiocese, said the property where the school is located is part of the unified Our Lady of Unity parish, which has “multiple worship sites,” and the church campus where the school is located is “no longer needed.” Quiroz said there is no additional information about potential buyers or how the property might be used in the future.

It’s unclear what would happen if a developer or another private buyer purchases the campus. The school has a lease for the building through the 2025-26 school year, Quiroz said.

The Zillow listing says the neighborhood is in high demand, and the plot has the zoning to build 48 units.

Villegas and Rivas held the press conference to urge Chicago Public Schools to purchase the building. CPS has already proposed to budget $20 million this fiscal year for “incubation” costs as it works to transition the five Acero campuses into district-run schools, according to a district budget presentation this week. The district is facing its most severe budget crisis since at least the pandemic. However, Rivas argued that it’s possible to negotiate an affordable deal for the building. Part of the expenses CPS has already accounted for, according to Rivas, is fixing Santiago’s roof.

“If CPS is saying that they’ve earmarked millions of dollars to replace this roof on a building that isn’t ours, I’d much rather work on finding a deal with the Archdiocese to be able to take over this building,” Rivas said.

Acero, which will oversee the school until next year, did not respond to a request for comment. CPS did not say whether it is considering purchasing the property.

“Regardless of the building’s future ownership, the District’s primary focus is on ensuring a smooth and successful transition for all students and staff,” Sylvia Barragan, a CPS spokesperson, said in a statement.

Acero abruptly announced last fall that it would close seven of its 15 campuses, including Santiago. After pressure from staff and families, the Chicago Teachers Union, and the mayor’s office, the Board of Education voted in February to save five of the campuses and turn them into district-run schools. Some board members opposed the move because they wanted the opportunity to consider whether absorbing the schools would be a viable decision amid district financial pressures.

As district enrollment has largely dipped over the past decade, the same has happened in Chicago’s charter sector, prompting several networks to call for consolidations and closures.

Rivas said co-locating Santiago with a nearby district school is not an ideal option because doing so would require complicated coordination between two different sets of staffers and school leaders.

“I’d much rather that we try to get this done as fast as possible to ensure that our families know they’re here for years to come,” Rivas said. “We’ve already made that commitment as a board.”

Erick Alonzo, father of a fifth grader and eighth grader, said his girls felt relief when the board blocked the closure. Last year was “very hard” on his daughters, who have attended Santiago since kindergarten and faced the prospect of leaving their friends.

Alonzo’s older daughter will move on to high school elsewhere after this school year, but his younger child once again faces the possibility of leaving Santiago sooner than she anticipated.

“If they sell the building, then you know, she’s gonna have to start making new friends and going to a different school,” Alonzo said, before hugging his girls goodbye for the day.

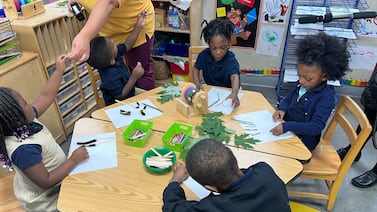

The school’s close-knit culture was apparent Thursday morning as children and parents pulled up to the school.

Alexandra Pabon, joined by her 17-year-old daughter Isabelle, dropped off Pabon’s 10-year-old son. The family used to live around the corner and later moved about a half-hour out of the neighborhood but has continued coming back to Santiago. They like that the school, which enrolled just under 230 students last year, has small class sizes and everyone knows each other.

Isabelle, who attended Santiago from kindergarten through eighth grade, embraced an old teacher, who talked to her for several minutes.

“A smaller school like this, it seems like you’re getting less experience, but it’s actually more impactful for your life because you form kind of like a family bond, not just with your teachers but with your friends,” said Isabelle, a senior at an Intrinsic charter high school downtown. “The teachers still see me, and it’s like I never graduated.”

Just before the first day of school started Thursday, a little girl wept outside the front doors. As her mother knelt down to reassure her, a Santiago staffer approached and said, “C’mon, we’ll go find our friends.”

The staffer invited the mother as well, and the three walked in together.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at ramin@chalkbeat.org.