The Detroit school district launched an accelerated version of its online learning plan this week, giving students with technology access an opportunity to see their teachers and classmates in person via live lessons in subjects such as math and English since schools shut down because of coronavirus.

The 90 percent of Detroit district students without computers or tablets continue to use paper academic packets, but the district added the chance to have phone conversations with their teachers. During a Thursday press conference, superintendent Nikolai Vitti said that only 10 percent of students were able to consistently access online resources.

Teachers spent last week learning how to use Microsoft Teams, the platform the district is using.

Vitti also said that the district distributed 30,000 academic packets this week, which is the same content available online. So far, the feedback the district received from teachers has been positive.

“Teachers generally appreciated the developed curriculum and the quality of the Teams platform,” he said.

Chalkbeat spoke with students, a parent, and a teacher about the challenges of learning in a time of heightened anxiety and stress due to the coronavirus. All of them dearly miss connecting inside the classroom.

Ciara Cade, student, Cass Technical High School

The transition to online learning this week has been rough for Ciara Cade, a high school junior who thrives on the connections she has with her teachers.

Without those spontaneous, in-person exchanges, she said that learning is dull, and online learning hasn’t made it much better.

“It feels like I’m in a box talking to my classmates,” she said. “It’s so awkward to join this thing and to be sitting here in my room and I’m just talking to all my friends. I feel isolated.”

Despite those rough patches, she says logging on to learn is a positive, productive thing to do while confined in her home on Detroit’s east side.

The 17-year-old starts her day around 8:30 a.m. in her bedroom, sitting at a tiny desk stacked with physics and chemistry books. She dreams of becoming an astronaut, but all the hours she’s spent alone during the pandemic are giving her pause about a career that requires a fair amount of isolation.

Sometimes her mind wanders. On Thursday, she couldn’t stop worrying about the health and safety of her teachers.

“Not being able to keep in touch with some of my teachers for a few days is kind of scary because you’re wondering, Are they OK?” she said. “People have relatives die or pass away. And you have to watch them try and continue everything the next day.”

As far as learning goes, Ciara is staying optimistic.

“We’re trying to do the best we can to try and keep everything normal,” she said. “It’s not a productivity contest.”

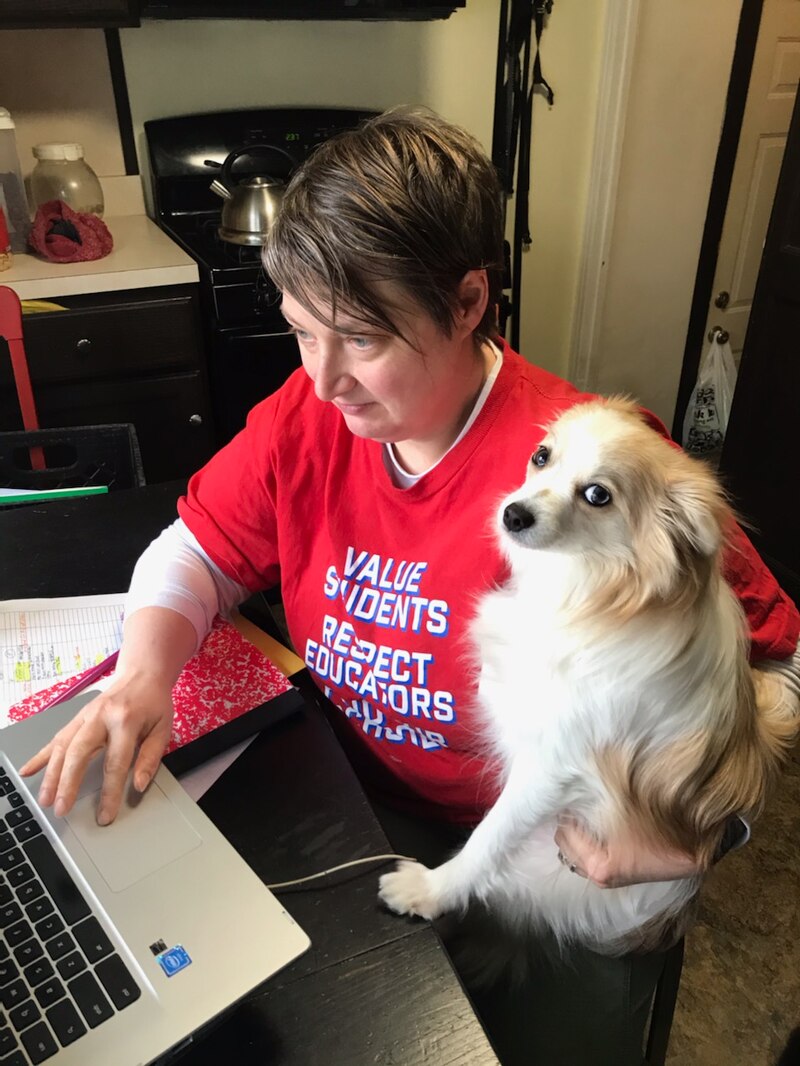

Alaina Larsen, teacher, Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts

One of the hardest parts for Alaina Larsen is losing out on watching her fourth-grade math and social studies students grow. She loves seeing her students become more independent.

“I miss the magic,” she said, her voice breaking as she held back tears over the phone.

She teaches live online between 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. from Monday through Thursday, and 2 p.m to 3 p.m. on Friday. She’s working hard to replicate the stability of her classroom.

There have been some growing pains. Adapting to each student’s needs has been an adjustment. Larsen is all about efficiency, drilling down concepts before advancing to the next step, and distance learning makes it hard to see if her students understand all the concepts.

Her style of teaching changes depending on whether she’s communicating with students online or by phone.

She shares her cell phone number with families and encourages them to call if they don’t have a computer or tablet at home as they work through fractions, the focus of her instruction these past few days. She’ll walk through how to tackle an equation over the phone, then tell the student to work on it alone and then call her back to tell her they figured it out.

Teaching during coronavirus has challenged her as a teacher, but she welcomes the opportunity after almost 20 years in the classroom.

“That’s so powerful to kind of reach everybody and give out to all the students equal access to us,” she said.

Larsen also makes space for her students and their families to share sorrows and fears. When everything becomes overwhelming, she takes time to relax grabbing a cup of coffee, walking her dog, or tending to her hostas and lilies at her Eastpointe home.

Darlene Waller, parent, and Elaina Waller, student at Greenfield Union Elementary-Middle School

Little changed this week for Darlene Waller and her daughter Elaina, a first-grader with autism.

The Wallers are among the 90 percent of families in the district who can’t access the district’s online educational resources. Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said this week that just 10% of Detroit students have been able to consistently learn online.

Darlene’s laptop was damaged by a virus, and the tablet she bought for her daughter doesn’t have the capacity to do the online work. She’s relying on phone calls with Elaina’s teachers and the paper academic packets.

She has teachers, who have done a good job of helping Elaina understand and retain reading and math information.

Darlene briefly homeschooled Elaina last year, and she’s always on the hunt for the best learning materials and supplementary resources.

“Focus on subjects that they like. And if the school curriculum is just too much, if it’s just causing too much anxiety and stress, you know, kind of try to build your own curriculum around that,” she said.

Darlene and Elaina get up between 5:30 and 7 a.m. each day to brush Elaina’s teeth and eat breakfast. She makes sure Elaina has time to play with her toys, like her ball maze, to help break up the day’s routine. They end the academic day around 2 p.m.

Darlene hopes that the time spent on Elaina’s education during these early years will stay with her into adulthood.

“I had to unlearn the fact that not all kids go through the same milestones,” Waller said. “I really hope and pray that she’s able to be self-reliant, self-sufficient, because I won’t be around forever.”

Eva Oleita, student, Cass Technical High School

A couple of days ago, Eva Oleita was having problems with her internet connection. She doesn’t have a laptop, so she used her phone to log into the district’s online program. Nothing worked.

“It’s been kind of difficult for me. Because, you know, I can only do so much on my phone as it is,” she said.

She was able to log into the system twice this week to catch up.

In one of her classes, she’s learning about how COVID-19 compares to the Spanish flu. Eva said the lessons have been beneficial to help her combat disinformation and learn how to protect herself. Her mother is a nurse working in hospice care who was previously exposed to COVID-19.

“As teenagers, we might be a little bit more naive. And we might be, you know, they might be able to sway our thoughts with it,” she said. “So I think it’s actually good that we’re learning about it.”