Michigan schools cut the “flunk” out of the state’s controversial “read or flunk” law, holding back fewer than 7% of students eligible for retention because of poor reading scores.

A report released Monday by researchers at Michigan State University found that Michigan schools planned to retain just 229 Michigan third graders out of 3,477 students who scored poorly on the reading portion of the state’s standardized test, the M-STEP.

The analysis is based on reports provided to the Michigan Department of Education by school districts this summer that detailed retention plans for individual students.

Michigan law allows for wide exemptions, and schools and parents used them liberally, promoting more than 93.4% of students who were a grade or more behind in reading in last spring’s test.

That means just 0.2% of all third-graders were held back last year because of the Read By Grade Three law, during an academic year that was interrupted repeatedly statewide by the pandemic and virtual learning.

While complete data won’t be tallied for months, it likely means that third-grade retention levels won’t be dramatically different from previous years despite fears that thousands would be held back.

In 2019-20, the most recent school year unaffected by the pandemic, 0.65% of third graders were held back.

The 2020-21 school year was the first year the retention part of the law was in effect. A number of education leaders, including State Superintendent Michael Rice and members of the Michigan Board of Education, urged lawmakers to pause the retention rule this year, citing the ongoing pandemic. Many school leaders said they did not intend to hold back students.

Even though few students overall were retained because of reading scores, the MSU report found that Black students were more than twice as likely to be retained as white students.

Students eligible for retention who were in poverty also were more than twice as likely to be held back as their higher income peers who also were flagged for retention.

“We have evidence of the inequitable implementation by local school districts of the Read by Grade Three law in Michigan,” Katharine Strunk, director of MSU’s Education Policy Innovation Collaborative, which conducted the analysis, said in a statement.

“Even when we account for which groups of students were eligible for retention to begin with, Black and lower income students and students in districts that were lower achieving before the pandemic were more likely to be retained at the end of the 2020-21 school year,” Strunk said.

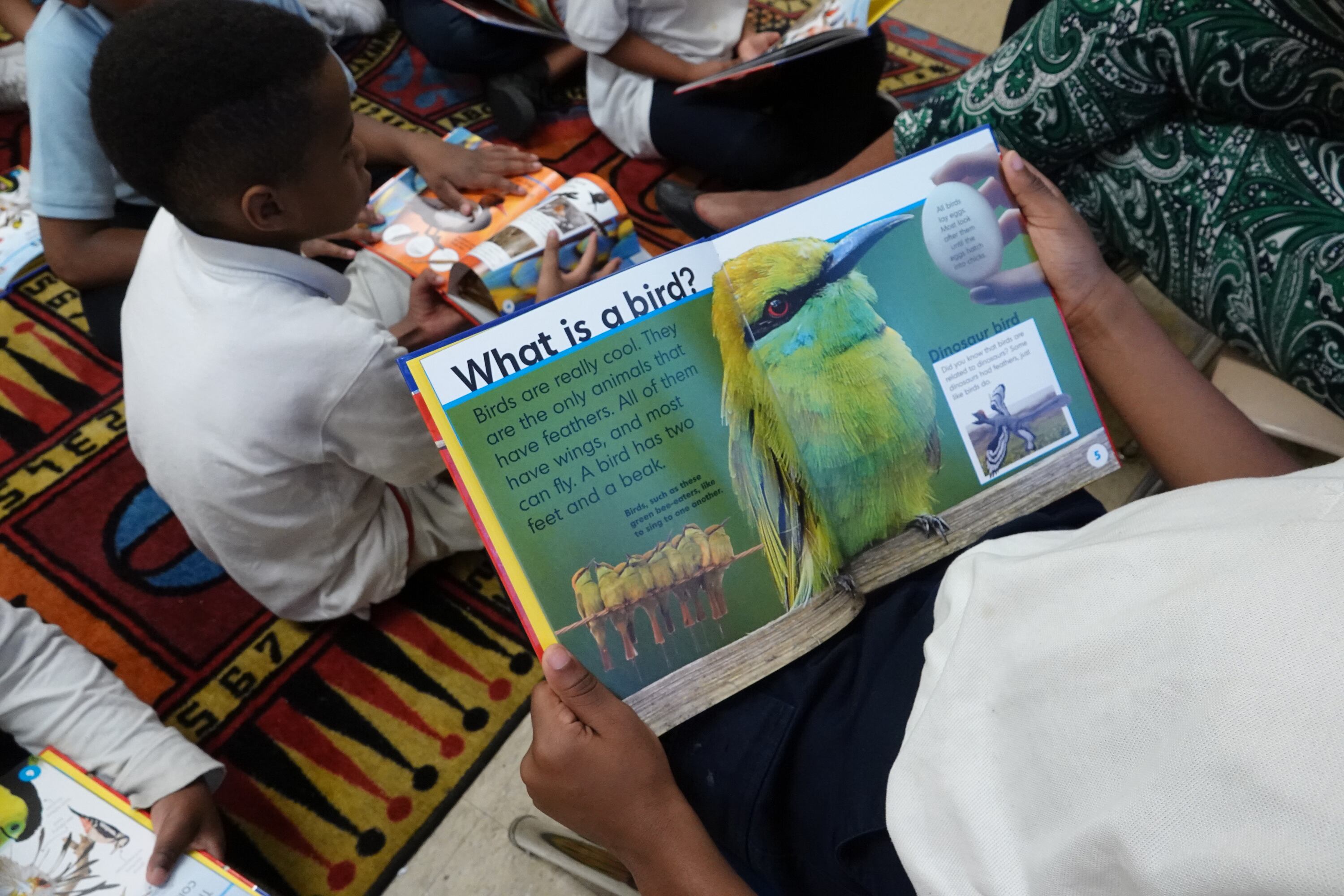

Experts view third grade reading skills as a key to improving Michigan’s schools, which rank in the middle of the pack among the states in academic achievement.

Michigan ranks 34th in the percent of adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher. Former Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican, and current Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer both advocated for increasing the percent of adults with post high school credentials to help boost Michigan’s economy.

In 2016, the Michigan Legislature passed the law that requires students who are more than a grade level behind in reading by the end of third grade to be retained. At least 15 states have similar laws.

According to the MSU analysis, more than 75% percent of districts with at least one student eligible for third grade retention intended to promote them all. More than half of all reported exemptions were based on parent requests.

“Educators understand that holding kids back doesn’t change their ability to read or get them in a better position to succeed,” said Bob McCann, executive director of the K-12 Alliance of Michigan, a school advocacy organization.

Retention increases the likelihood students will drop out, said Paul Liabenow, executive director of the Michigan Elementary and Middle School Principals Association.

“There are times when it can be effective to hold students back, but as a regular practice it tends not to work,” he said. “The social and emotional impact is fairly dramatic.”

Whitmer and Rice are longtime critics of the read-or-flunk law. Education department spokesperson Marty Ackley said Monday that the agency “respects the decisions made by local school leaders and parents on a student-by-student basis.”