Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

When it was time to choose a school for his daughter, Mike Sotiropoulos debated selecting one outside of Ypsilanti Community Schools, his home district.

Under a longstanding state law, he had the option to look elsewhere. He considered Ann Arbor Public Schools, which has better test scores than Ypsilanti, but ultimately decided to stay in YCS because of its International Baccalaureate programming.

“A lot of times I feel like schools put too much emphasis on (test scores) and less emphasis on other things that we were more interested in,” said Sotiropoulous, whose daughter now attends Ypsilanti International Elementary School. “We just wanted to get our daughter to a school with caring staff and maybe a little bit more emphasis on learning by play.”

Another parent, Marissa Harding, made a different choice. A lifelong resident of Ypsilanti Township and a former paraprofessional in the school district, Harding believes the quality of instruction has suffered since Ypsilanti Public Schools merged with Willow Run Community Schools in 2013 and rebranded as Ypsilanti Community Schools, or YCS. She enrolled her child at Global Tech Academy, a charter school located across the street from Ypsilanti Community Middle School, on the east side of the district.

“I hadn’t been hearing the best things about YCS in the past few years,” Harding said, adding that part of Global Tech’s appeal was its small class sizes.

More than a decade after the two school districts merged, YCS has worked hard to get parents like Harding and Sotiropoulos to enroll their children, with aggressive marketing campaigns that promote the two communities, once fierce rivals, as “stronger together.” Still, more than half of the students who reside in the district’s boundaries choose to attend school somewhere else, according to state data.

With K-12 enrollment declining statewide, state officials have encouraged consolidation of schools, or even districts, as an option to pool resources. In many ways, what has happened in YCS is a case study of the ups and downs of mergers, a strategy that is often unpopular with school communities and families. In Michigan’s competitive school environment, it also can be difficult to stand out when families can select from an array of charter schools and schools outside their home district through the state’s nearly 30-year-old “schools of choice” program.

In a statement, Carlos Lopez, assistant superintendent in YCS, acknowledged that the appeal of neighboring school districts and charter schools can pose a challenge in attracting and retaining students. YCS’ boundaries, which encompass the City of Ypsilanti and two surrounding townships, include 8,227 K-12 students. Of those, 4,317, or about 53%, chose not to enroll in the district’s schools this year, state data shows.

After enrolling more than 4,500 students in its first year as a combined district, YCS saw an immediate decline, dropping down to 3,699 five years ago. Since then, the district has increased

its enrollment by 8% to 3,872. It also has seen an uptick in the number of students using schools of choice to enroll, with 488 this year — the highest total YCS has seen since the two schools merged.

Lopez attributed the recent increase in enrollment to new, innovative programming, such as the K-12 International Baccalaureate, an elementary Spanish immersion program, and STEAM programs in every school.

The district also moved its middle school into the former Willow Run Middle School building last fall. The move was made, in part, to reconnect with the east side of the district, where some parents felt Willow Run’s roots had been neglected, Lopez said.

School district mergers are often an unpopular choice. But at the time of the merger, Ypsilanti and Willow Run were in such financial peril that the districts risked state takeover, said former Washtenaw Intermediate School District Superintendent Scott Menzel, who oversaw the process.

Other districts had set an example of what could happen: Detroit had undergone a state takeover. Inkster Schools was dissolved around the same time, with its students spread across four neighboring school districts. Consolidation seemed like a better outcome, he said.

“In order to get a different outcome than what we had seen previously, we had to really take advantage of the opportunity to truly hit the reset button,” Menzel said of the community support for the merger. “That meant doing some things that were uncomfortable and having people interview for their jobs. We had to tackle the difficult questions about how many buildings needed to be open and how do we ensure that both communities are served well in that transition.”

Still, district mergers remain uncommon. Rather than consolidate, other school districts in Michigan have opted to reduce the number of school buildings and make infrastructure improvements — efforts supported with “consolidation grants” awarded in April by the Michigan Department of Education.

Flint Community Schools, with a $35.9 million state grant, plans to close four of its 11 school buildings and build a “state of the art” high school, according to the state. Union City Community Schools, with a roughly $23.6 million grant, plans to demolish a middle school and renovate elementary and high school facilities, reducing its buildings from three to two.

And North Central Area Schools plans to use a state grant of $15.4 million to upgrade its facilities and decrease its footprint from two buildings to one. The project includes “investments in technology, flexible classroom spaces, and modern amenities that support innovative teaching and learning,” according to the state.

“The ability to keep our students safe and secure while also improving our aging facilities makes this a game-changing moment for our district and our entire community,” Union City Superintendent Chris Katz said of the grant. “We love our small-town atmosphere. These funds coupled with additional dollars from our voters will put us in a strong position for many years to come.”

YCS loses students to charters and neighboring districts

By 2012, the year before the merger, both Ypsilanti and Willow Run had steadily declining enrollment driven by academic achievement issues, families selecting charters or other public schools through schools of choice, and subsequent budget woes.

Voters approved a merger of Ypsilanti and Willow Run schools by a 61% vote that year.

Schools of choice, which passed in 1996, gave students additional enrollment options, including letting them select their school within the home district. While optional for districts to participate in, schools of choice also permitted local school districts to enroll students from other districts within the same intermediate school district.

In its final year, Willow Run’s enrollment was just 1,442, down by nearly half from 2,673 in 2003.

At first, Ypsilanti seemed like it was in a better position than Willow Run. It opted into schools of choice early on, gaining 1,091 students in 2009 from other school districts, while losing just 436 to other public school districts from within its boundaries.

That advantage wasn’t enough to cover the additional loss of students to charter schools, however, causing Ypsilanti’s budget issues to intensify, with the district losing nearly twice as many students to schools of choice as it gained by 2012.

Both school districts faced a “death spiral,” said Menzel, former superintendent of Washtenaw Intermediate School District, the intermediate school district for Ypsilanti and Willow Run.

Menzel, who facilitated the 18-month consolidation process between the two districts, said pitches from neighboring districts and charter schools drew some parents away as Ypsilanti and Willow Run grappled with budget issues and the prospect of closing school buildings.

While the legacy debt both districts carried into consolidation has been relieved by the state, YCS still struggles to keep its students in-district, he said.

“As soon as other neighboring schools saw that opportunity, because the money follows the kid, they took advantage of it,” said Menzel, who is now the superintendent of Scottsdale Unified School District in Arizona. “In a competitive choice and charter environment, people are always working to recruit kids, and those who had the ability to leave left.”

National Heritage Academies, which operates several schools within YCS boundaries and Washtenaw County, has been a strong competitor for the school district, increasing its enrollment in the Ypsilanti area after the two districts merged.

NHA schools account for more than 1,300 of the 2,600-plus Ypsilanti-area students who enrolled in charter schools, like Fortis Academy in Ypsilanti Township and South Pointe Scholars in the heart of the former Willow Run district.

NHA Spokesperson Leah Wheatlake said parents who choose charters are seeking educational opportunities for their children because they “want more for them than they had.”

“Choice provides parents that advantage – to choose the educational setting that meets their family’s needs,” Wheatlake said. NHA schools point to higher test scores, a “safe environment,” and character-building curriculum as some of the reasons that parents select them.

Ann Arbor Public Schools has been the most popular public school choice for families living within YCS’ boundaries, along with Lincoln Consolidated Schools and Van Buren Public Schools. Ann Arbor began participating in schools of choice in 2010 to counter the losses of its own prospective students. Of the 2,008 students who enrolled in Ann Arbor from other districts in the 2024-25 school year, 1,001 were from YCS, according to state data. That’s up from 220 in 2012-13, the year before the merger.

Dawn Linden, assistant superintendent in Ann Arbor, said the district uses schools of choice to cover expected shortages and to counteract the loss of its own students to neighboring school districts and charters. It offers seats to in-district students first, before opening remaining slots to students using schools of choice.

The law doesn’t allow school districts to select which students it wants to enroll or to control how many students come from a particular school district, Linden said.

“There’s no ‘Hey, we’re going to take a certain maximum from this school district and that school district,’” Linden said. “The rules for schools of choice do not allow for that, nor would we want to.”

Parents’ school choices reflect location, test scores, housing options

For parents considering Ypsilanti Community Schools, a number of factors are in play, from location to test scores to perceptions of the school system that have lingered since the merger.

After sending his son to Ypsilanti International Elementary through third grade, Djaun Boyd said he felt like teachers weren’t able to connect with him and challenge him to learn. He transferred him to the nearby South Pointe Scholars charter school last fall. His daughter, on the other hand, is enrolled in Lincoln Consolidated Schools’ early childhood program at Model Elementary.

Boyd said each family’s situation requires a different approach, but he has been happy with his decision to move away from YCS.

“My son is going to thrive wherever he’s at,” Boyd said. “We felt like it was better for him to thrive over there [South Pointe] because there wouldn’t be any more distractions.”

Harding said she couldn’t shake the feeling that Ypsilanti Community Schools hadn’t been embedded in the community the way that Ypsilanti and Willow Run schools were prior to the merger. She said she didn’t see the different student groups, like bands or choirs, at popular Ypsilanti events, or hear about the district’s accomplishments in the news.

“They were very successful, good graduation rates, you know, kids going to college, stuff like that,” Harding said of the district prior to the merger. “Even by the time I got there, it wasn’t as good as they had been in those years. It’s kind of just dropping off, getting worse in recent years.”

Those who remember the two districts before consolidation might view Ypsilanti Community Schools in a different light than those who moved into the district more recently.

Steve Kwiatkowski moved to the city with his family after a failed attempt to buy a home in Ann Arbor. He heard good things about the Ypsilanti schools from other families and decided not to pursue other options.

“I know [Ann Arbor Public Schools] has such a great reputation, but we already spent so much time in Ypsi, going to the coffee shops and restaurants and kind of like the vibe here,” Kwiatkowski said.

Matt Kirkpatrick, who has lived in Ypsilanti since 2014, said his child was offered a spot at Carpenter Elementary in Ann Arbor Public Schools, but ultimately decided to enroll his child at Ypsilanti International Elementary because of the pathway it offers to the well-regarded Washtenaw International High School.

“The school felt like our community,” he said. “We knew a lot of our parent friends were sending their children to school here, which is a factor, too.”

Sotiropoulous felt if he was going to live in the Ypsilanti community, he should support the local school system.

“We’re Ypsi residents, so we felt like if we could get her into an Ypsi school that would be better than sending her to Ann Arbor for schools of choice,” he said.

For many parents, school decisions are often circumstantial and can change.

Laura Herbert home-schooled her two children before her daughter expressed an interest in attending public school a year ago.

A Ypsilanti Township resident, Herbert didn’t give YCS serious consideration. She wasn’t impressed by the district’s test scores and described the school buildings’ conditions as “subpar.” She found a better fit at Washtenaw International Middle Academy, an Ypsilanti-based public consortium and International Baccalaureate school.

“I felt like it was the best option that we had for a public school, and because we’re in Ypsi, she can take the bus,” Herbert said.

Some parents attend Ypsilanti schools because they don’t feel the choices available are workable for their family.

“The reason why my kids go to Ypsilanti Schools is because it’s closer,” said Teaha Jackson, who has 10 children enrolled in the district and noted that transportation isn’t included in schools of choice.

Ypsilanti wants to replant roots in Willow Run

No building is more representative of Ypsilanti Community Schools’ recruitment efforts than its middle school. Constructed as Willow Run Middle School in 2004, the building sat vacant for nearly a decade before the district brought students back last fall.

The building has some advantages over the old East Middle School, where students had learned since the 2018-19 school year. It is 45 years younger and almost twice the size, offering two gymnasiums, a large auditorium, and “dens” for each grade level, which help avoid altercations by keeping grades separate during class transitions throughout the day.

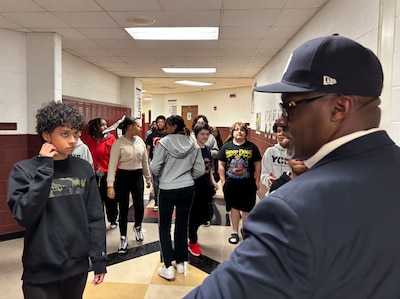

With newer amenities and more space, Ypsilanti Community Middle School Principal Charles Davis said he has made it his mission to make sure students don’t attend the charter school across the street.

“I want every fifth grader who attends [elementary in Ypsilanti] to attend school here — we want every last one of them,” Davis said. “We’re very intentional about keeping our students and welcoming others.”

The district has implemented a number of measures over the years to curtail fights in the middle school setting, including bringing in a team from the Detroit-based 180 Program to act as behavior interventionists who can free teachers and administrators from the burden of disciplinary referrals.

Several students said the new building has made them feel safer.

“In the old building, you were kind of scared of getting jumped,” Elovie Mazama, an eighth grader said. “It was more chaotic in the old building, and we would have fights every week. In this building we barely have any fights.”

Menzel, the former superintendent who facilitated the consolidation of Ypsilanti and Willow Run, said the combined district still faces some of the same challenges when it comes to attracting families in a competitive environment. But he believes YCS is stable with positive signs for the future.

“I think it’s a testament to the strength of the process that more than a decade later, Ypsilanti Community Schools still exist in serving kids in the community, and they’re doing some very innovative and creative things to try to draw people back into the system,” he said.