This story was originally published by Bridge Michigan, a nonprofit and nonpartisan news organization. To get regular coverage from Bridge Michigan, sign up for a free Bridge Michigan newsletter here.

LANSING — Some Michigan schools are taking out loans, warning of food service cuts and possible preschool closures as lawmakers struggle to finalize a state budget by an Oct. 1 constitutional deadline.

Without a deal in the next week, the state government will shut down. Schools would stay open, but an extended impasse would jeopardize critical state funding, and educators are already preparing for that possibility.

If there is a shutdown, “the shorter the better” for Michigan schools, said Craig Thiel, research director at the nonpartisan Citizens Research Council. “The longer, the more uncertainty, the more work.”

For most of the past decade, lawmakers and the governor have finalized an education budget by July 1 to align with when the fiscal year begins for K-12 schools. That didn’t happen this year despite a deadline written into state law.

Now, a Republican-led House, Democratic-led Senate, and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer have just seven days left to agree on a state budget expected to include $21 to $22 billion for public K-12 schools and pre-K programming.

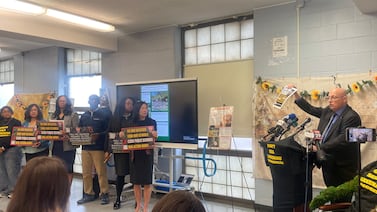

Whitmer on Monday criticized what she called “shortcomings” with a House GOP budget, but said she still believes a shutdown is avoidable.

“I think we can write a budget that checks off things on my list, checks off things that are on House Republicans’ list and the Senate Democrats,” she told reporters at an event in Kentwood.

State payments loom

The state budget funds schools on a per-pupil basis — $9,608 this year.

Districts receive that funding in 11 monthly state payments. The next is due Oct. 20 but would not go out if the state government is closed, which officials say could jeopardize bus service, after school programs, free meals, and more.

“In a shutdown, no state school aid flows,” the Michigan Department of Education warned in a Sept. 2 memo.

Education leaders warn a state government shutdown could impact some community child care providers even sooner — in early October, leaving them unable to make payroll.

The uncertainty is prompting moves from educators that could have a lasting impact on the financial health of some Michigan school districts, including high-interest loans and delayed hiring decisions.

“There are school districts like mine that are borrowing way more money than we should ever have to because of all these uncertainties being created in Lansing,” said Laingsburg Community Schools Superintendent Matt Shastal.

Already one in 10 school districts say they’ve made classroom personnel cuts ahead of this academic year, according to a survey of school district leaders, though not all cuts are necessarily because of budget uncertainty.

Some, like House Speaker Matt Hall, R-Richland Township, say they’re still “optimistic” leaders can avoid a government shutdown despite recent state budgets taking weeks to negotiate.

Any cuts schools are already making are “performative,” Hall recently argued, noting proposed budgets would each raise the per-pupil rate — to $10,008 in the Senate-proposed budget to up to $12,000 in the House-backed plan.

“If I was a school superintendent … and I saw that all parties wanted to increase my funding, I wouldn’t be making all of these crazy decisions,” Hall told reporters last month.

This weekend, Hall said that even if lawmakers can’t finalize a full budget by Oct. 1, he’s “hopeful” they can at least agree on an education spending plan “before there’s a shutdown, if there is one.”

Universal meals program at risk

With the potential government shutdown looming, several Michigan school districts are warning parents that school meals may not be free for all for long. They’re urging parents to fill out forms to assess whether their kids qualify for free or reduced price meals under federal programs instead.

“Students not qualifying for federal free or reduced benefits will not be eligible for free meals ” beginning Oct. 1 if there’s no funding certainty from the state, Bloomfield Hills Schools told parents last week.

Backed by Whitmer, Michigan’s universal free meals program covers costs for students who do not otherwise qualify for free meals through federal programs because their families earn too much money.

All students have qualified for free meals for the last two school years, and state funding currently goes through September.

The Michigan Department of Education has called on the Legislature to continue funding universal meals through a dedicated pot of funds. A budget plan approved by the Republican-led House did not include that funding, but it would give schools more discretionary money, allowing them to continue the universal meal program if they choose.

Whitmer said Monday she opposed the GOP approach, arguing it’s “important that we designate dollars for lunch and breakfast” in the budget. “If we don’t do that, we run the risk of some kids having access to meals and others not.”

In the meantime, Ann Arbor Public Schools has said it will start charging families for meals in October if a budget deal with universal meals is not approved. Midland Public Schools said it will offer free breakfast for the full school year but start charging for lunch in October if a deal is not reached.

Huron Valley Schools said in a Sept. 12 notice it would use its “Food Service Fund surplus to continue offering free breakfast and lunch to all students for as long as possible.”

Okemos Public Schools officials previously announced the district would not offer free school meals to all students this year, in a move the superintendent blamed on a lack of guaranteed funding from the state.

A child care crunch

Paula Martin, director and teacher at Kidtime Child Development Center, in Lansing, said if lawmakers do not finalize a state budget soon, she may need to close her preschool for 4-year-olds in early October.

“How does it affect these children if we have to shut down and then later in a couple weeks say ‘come back?’ It’s going to be like starting school all over again from day one,” she told Bridge.

Martin operates her pre-K through the state’s Great Start Readiness Program, which provides funding for local schools, nonprofits, and businesses to provide no-cost preschool for 4-year-olds.

In Ingham County, that funding is first distributed by the intermediate school district, typically before the Oct. 20 state payment comes through so that those businesses make cash flow, according to Superintendent Jason Mellema.The first of those payments would typically go out Oct. 3.

Kidtime would normally get its payment Oct. 10, according to Martin.

“Where would we get those funds from? That’s a lot of money,” Martin told Bridge, noting about 80% of her operational funding is at risk.

It’s not clear if other intermediate school districts normally distribute funds earlier in the month. Thiel said he is not aware of others, and leaders in Oakland County and Midland County said they were not aware of pre-K providers saying they may shut down soon.

Emily Brewer, associate superintendent of early childhood at the intermediate district, told Bridge that the district works with 13 community based providers for pre-K. About half of them would likely be “in danger of not being able to make their payroll payments without a state aid payment” in October.

The tuition-free pre-K program used to be limited to the state’s neediest students, but the Whitmer administration is working toward making pre-K free for all 4-year-olds, regardless of income.

Brewer said Ingham County is also prepared to open up more classrooms and has a waitlist of students. But without budget certainty, parents are in a waiting period.

“Unfortunately I worry people are going to lose faith in the system because we have a lot of people on the waitlist,” Brewer said.

The director of the Michigan Department of Lifelong Education, Advancement, and Potential said in a statement last week that the House Republican budget would lead to fewer students in the pre-K program and fewer new classrooms.

The uncertainty could trickle down to child care for younger children too.

Providing infant and toddler care is costly and centers must staff those at a higher adult-to-child ratio than 4-year-olds.

Centers use the state pre-K program to help recoup some of the costs of caring for younger children. Brewer said she thinks it’s a “possibility” that care for younger kids is cut back in the meantime.

High-interest loans

Taking out loans to cover operating expenses isn’t out of the ordinary for Michigan schools, but some districts are opting to take out more than they may need just in case a state budget isn’t signed into law by Oct. 1.

That’s the case in Laingsburg, which opted to take out a $1.7 million loan earlier this month, according to Shastal, the superintendent.

That money will mostly go toward paying teacher salaries and other instructional expenditures, which account for nearly 60% of the district’s spending, according to the most recent publicly available data.

Interest and fee payments on the loan, which will total $65,000, are enough to pay for one teachers’ salary.

The lack of a state budget has also prompted the district to hold off on replacing two newly retired teachers and reduce one educator’s workload from full- to part-time, Shastal added.

While not uncommon for the district to take out yearly loans, Shastal said the district this year borrowed “way more than we would have” in order to “make sure we could keep the lights on, the doors open and keep kids educated.”

The state has a program allowing districts to borrow funds at lower interest rates because of the state’s strong credit rating, Thiel said. But the deadline for that has passed, so districts may incur more costs when borrowing.

In a recent survey conducted by the Michigan Association of Superintendents and Administrators, 42 of 241 district leaders who responded said they have had to take out loans already.

More than a dozen districts said they would “have to consider closing down schools” at some point in October if a state budget isn’t done, said Tina Kerr, executive director of the association.

“After a certain period of time, you have to pay these loans back,” Kerr said. “You can’t borrow your way out of a hole like this.”

The Michigan government last shut down in 2007 and 2009 — but only a few hours. Those budget delays were quickly resolved without major disruptions to state operations — and long before any state school aid payments went out.

What about after-school programming, sports?

After-school programming could eventually be affected if lawmakers fail to strike a budget deal, according to officials.

The current state budget includes $57 million in grants for before-, after-, and summer-school programs.

That’s helped serve about 69,000 children across the state, providing homework help, tutoring, workforce development, and snacks, said Erin Skene-Pratt, executive director of the Michigan Afterschool Partnership.

Her group surveyed current grant recipients, and nearly 73% of respondents said they would have to reduce the number of children served if the funding was eliminated. Also, half said they have already “reduced enrichment activities” due to state budget uncertainty.

Major sporting events are not at risk, according to the Michigan High School Athletic Association.

“As far as anything we run, like Regionals or other postseason events, we will be playing as scheduled,” Geoff Kimmerly, MHSAA communications director, told Bridge Michigan in an email last week.

“While yes, the majority of our schools are public, we do not receive any money from the state government and our budget is instead derived primarily from ticket sales to our tournament events and then sponsorships.”

Isabel Lohman is a reporter for Bridge Michigan. You can reach her at ilohman@bridgemichigan.com.

Jordyn Hermani is a reporter for Bridge Michigan. You can reach her at jhermani@bridgemichigan.com.