Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free monthly newsletter How I Teach to get inspiration, news, and advice for — and from — educators.

Corey Rosser doesn’t have to go far in the rural community in which he teaches to see how much his former students have to offer.

When he goes to the bank, he’s likely to see students he taught at Quest High School, an alternative high school in North Branch Area Schools, working there. When his son broke his arm, the emergency room nurse was one of his former students. So was the coach for his son’s youth basketball team. And when their community needed a grand marshal for a Fourth of July parade, a former student who became disabled serving the country in the Middle East was chosen.

“The impact is everywhere in my rural community because my students are everywhere, and are the most likely to remain local,” Rosser said. “I am proud of the contributions my students make to the community they are now an integral part of.”

Rosser, Michigan’s Teacher of the Year for 2025-26, is a longtime teacher in an alternative program. He knows well the misconceptions people have about the students he teaches — that they’re lazy, unmotivated, have little to offer, and are unable to learn. He also knows well that those misconceptions couldn’t be further from the truth.

“They may either just be motivated differently or not motivated by what you are teaching,” Rosser said.

Often, it has nothing to do with education.

“When you have a student that works 40 hours a week to help pay their families’ bills, their poor performance has little to do with your curriculum. It has to do with competing interests,” he said. “My interest is the subject. Their interest is keeping the lights on. That is the challenge. You have to bridge that by providing an authentic learning experience that they see benefitting their lives.”

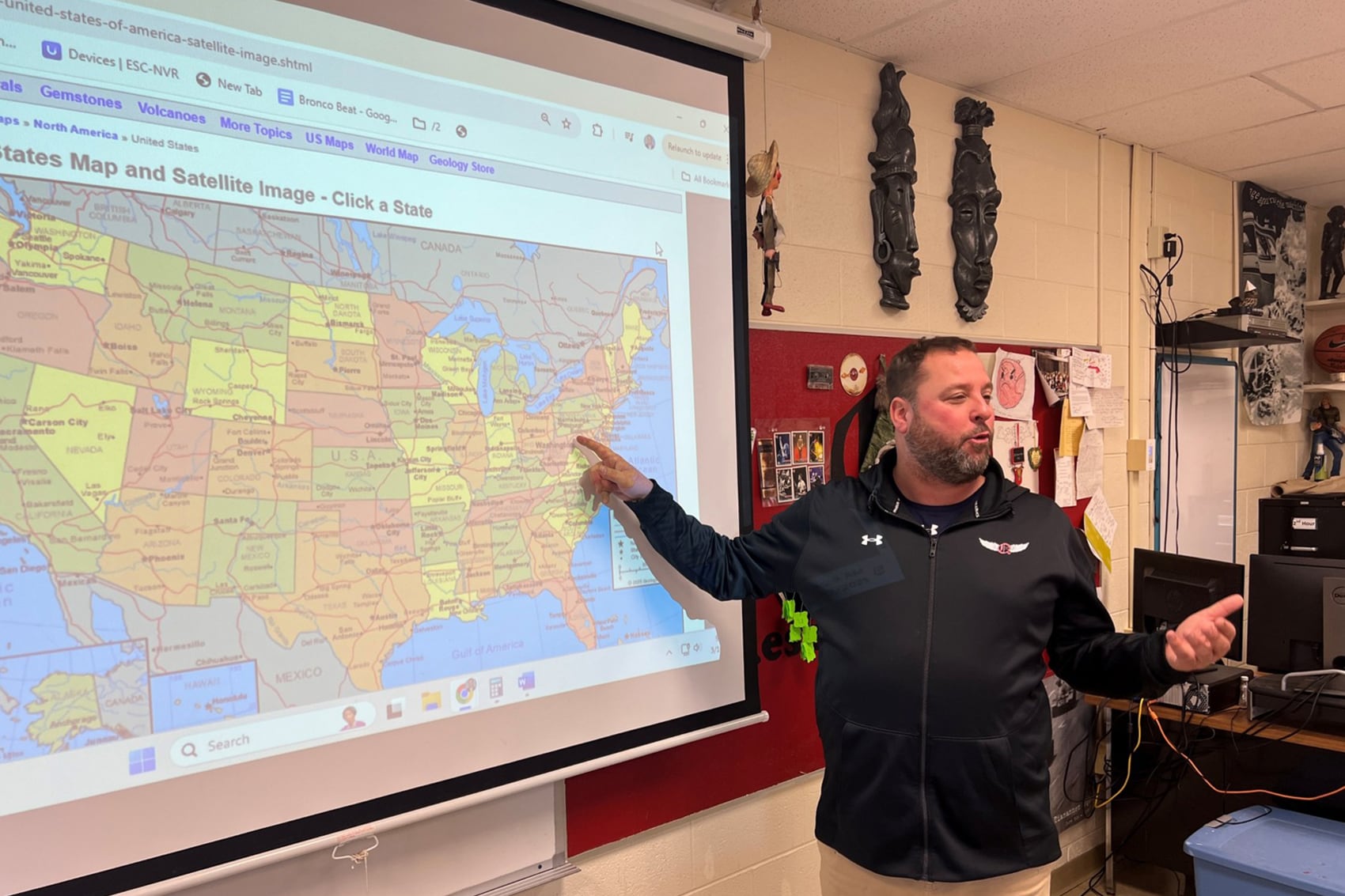

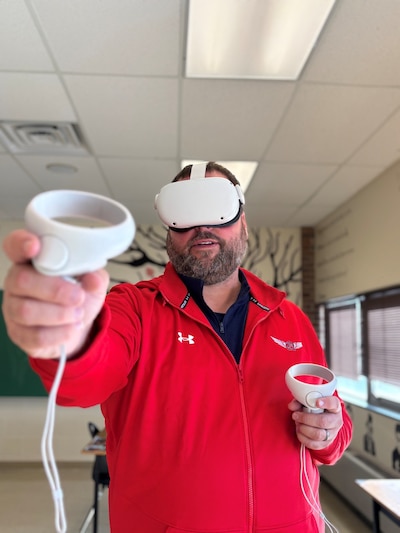

Rosser has been a teacher for 22 years and is the program coordinator and a teacher at Quest. He spoke with Chalkbeat about his career, his favorite lesson on political affiliation, and connecting with students.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How and when did you decide to become a teacher?

I decided to become a teacher after working at Teen Ranch, a juvenile detention center, during my college summer breaks. It was the first time that I found a calling that wasn’t about me … and even greater, was bigger than me. It was the first time I wanted to be “better” for the sake of helping others. I knew that teaching was what I was meant to do.

What’s your favorite lesson to teach and why?

My favorite lesson to teach about political affiliation through a political compass quiz. The political compass quiz asks students numerous questions about their ideology. At the end, it places them on a political compass scale that shows their leanings based on their belief system. As an educator, it isn’t about whether they identify with left or right leaning politics. It’s about their ability to articulate why they identify with a respective party. It forces students to think about what they believe and support that belief with sound rationale. It’s not teaching them what to think, but how to think.

After completing the test, students submit their results anonymously. I compile the responses and present them on a political compass chart, along with graphs and pie charts that display historical data from previous years’ students. This data allows students to identify trends and make inferences about the data. Engaging students through their direct participation in the political compass test draws them.

Additionally, we critically examine the validity of the political compass test itself. We ask important questions: What biases might exist in the test? What motivations could someone have for creating it? Were any questions slanted to favor one side over another?

This unit defines my teaching philosophy in several ways. I believe that the driving force of learning lies in questioning. We must strive to understand the world around us and identify how we fit into it. Each of us should have a set of principles guiding our behavior, and those principles should be consistent across all situations. Discourse is crucial, but even more important is understanding how to engage in discussions that lead to resolution.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your classroom (or your school)?

I don’t like to think of it as something separate. That being community and classroom. The classroom is the community; the community is the classroom. As educators, we get wrapped up in our four walls, our curriculum. Those are obviously important, but if students can’t see parts of their community in the classroom, and if my community can’t see the impact we are having in classrooms then we have failed. We work to remove those barriers. I work with great students and families, but with working with at-risk youth they have few mentors that drive the community. Connecting them to the community is crucial to helping them see their future success in it. That is true with our learning community and the community of North Branch at large.

How do you approach news events in your classroom? Please provide an example.

I think you have to approach current events understanding that not everyone perceives an event the way you do. Fake AI-generated news on social media platforms makes it difficult. People’s social media algorithm feeds them news similar to their previous clicks. It has divided us more than ever. The first step is to sift through what is “news”. By that, I mean, what can we confirm to be true. The 24-hour news cycle can make it difficult as well with evening reputable news sources wanting to break information on the story. We start there. What is real? What do we know? How might perspectives on the event be different? How can we respectfully discuss it, acknowledging different perspectives, and feeling our perspective heard?

How do you develop relationships with students who have struggled in a traditional school setting?

In my experience, developing relationships with at-risk learners is more difficult because they don’t particularly care about the ethos. They don’t care about what you have accomplished. They want to know what you can help them accomplish. Their path is full of well-intentioned adults who are successful with most learners, but fail to connect with them. You have to care consistently and relentlessly. They have to see that you aren’t going away. You have to value what they value. You have to incorporate it in your approach. It can’t be one-sided with the student being expected to meet you even in the middle, not at first. But more than the individual relationships, it begins with a culture. If you have a school with a strong, inclusive culture that will get you over the first hurdle.

How will you use your voice as Michigan Teacher of the Year to advocate for teachers and for students?

My message to students is to take advantage of every opportunity. We live in a country where all doors are open to you. Your decisions in school can keep them open or start to close them.

My message to all teachers: “You Are Enough!”

The challenges we face in education can often feel overwhelming. We are frequently told that we don’t do enough — whether by society, parents, community members, or even administrators. The most painful critiques come from our students.

Many students face daily challenges that are unfathomable to most. You owe it to them to put forth the best version of yourself. Your efforts are enough.

I feel like a failure, at least at some point during each day. Some days I know I have done everything in my power. Some days I feel like a fraud. Being recognized as Michigan Teacher of the Year has not changed that. YOU ARE ENOUGH!

Tell us about your own experience with school and how it affects your work today.

My own high school experience was very positive. I was a leader on my sports teams, captain and MVP of some. I was president of the student council. This gave me a very narrow view of what the high school experience was. I built leadership skills in so many ways. Early in my career, my view of students was that if they couldn’t achieve the same it was their lack of effort. I didn’t understand the many variables that kept them from the experience. More so, I didn’t fully understand that many of my students didn’t value those same things. The contrast between my experience and my students’ experiences was so stark it led to a lot of failure as a teacher early on. I was blessed to have great mentors to follow. I evolved and adapted to remain relevant in my students’ lives.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received, and how have you put it into practice?

The best advice that I received was that you have to let people try and fail. You can’t save them from every lesson they need to learn. Failure is the greatest teacher. When you rob a student of failure, you steal an opportunity to grow.

What’s one thing you’ve read that has made you a better educator?

I think one of the most influential books that I have read as an educator is “Detroit Divided.” The book was very eye-opening. Being from a small, rural community growing up, I tended to view the world as very black and white, right and wrong. There is much more gray than we care to admit. It showed me there was a deeper layer to any subject. While the book is a study of historical race relations in the Detroit Metro area, the theme can be applied in so many ways across social classes.

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.