Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and s tatewide education news.

For years, Indiana lawmakers tried but failed to change how schools handle issues related to race, sexuality, parental rights, and more.

In 2025, they finally succeeded.

As the Trump administration advanced conservative priorities through executive orders and other moves, state lawmakers have banned schools and teachers from implementing certain concepts about race and identity, including that a person should be blamed for “actions committed in the past.” That’s something they have tried to do since 2022.

They’ve also required school boards to post their sex education materials online, and codified parental rights over their children’s health care and education — two more ideas that didn’t make it through the legislature in past years.

The result is a suite of new social-issue laws affecting public schools that will go into effect in July, which could chill classroom speech and lead teachers to avoid topics “that could cause offense,” said Jonathan Friedman, an official at PEN America, which supports protections for freedom of expression.

“Across a number of states, it’s clear that the election of Trump has given legislators a green light to unleash education bills of their liking with fewer brakes and fewer boundaries,” said Friedman.

Despite the momentum, not all social-issue legislation made it over the finish line this year.

For example, a wide-ranging bill to ban teaching that racism and exclusion are part of the national identity died in committee. Another controversial bill to allow chaplains to serve as public school counselors that passed the Senate did not receive consideration in the House.

Here’s what these new laws will require of K-12 schools and teachers.

Ban on teaching ‘personal characteristics’ echoes DEI orders

Indiana lawmakers have tried since 2022 to pass a law limiting discussions of race and racism in schools.

While the terms for the ideas they’ve targeted have changed — from critical race theory and divisive concepts to diversity, equity, and inclusion — the bills have generally sought to ban teaching that any person is superior to another based on their personal characteristics or should feel guilty for historical events based on those characteristics.

But the proposals have faltered in the past in the face of intense criticism from educators and others who say the language would chill classroom discussions of history.

This year, however, SEA 289 passed into state law against the backdrop of federal and state orders banning DEI practices throughout the public sector. Those practices, Republican leaders have said, constitute unlawful discrimination.

The original bill introduced this year would have required schools to post curricular, instructional, and training materials related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and nondiscrimination, as well as race, ethnicity, and sex. It also would have banned schools from compelling students or teachers to “affirm, adopt, or adhere” to beliefs that a person’s character or relative worth could be determined by their “personal characteristics,” or that they could be blamed for past actions based on those characteristics.

As passed, the new law prohibits public schools from requiring employees to attend training sessions that include these ideas. It also says teachers can’t “implement” any of these ideas or “compel” students to do so — a slight departure from past bills that said teachers couldn’t “promote” these concepts during instruction.

It’s not yet clear how educators, schools, and parents will interpret this language,

said Chris Daley of the American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana. It’s possible, he said, that people could use it to target teachers who teach lessons that a parent objects to.

However, he said the language indicates a teacher would need to “clearly go beyond just including information about these topics in a lesson” in order to run afoul of the law. For example, a teacher would have to require students to take an action, such as writing a report.

Furthermore, the far-reaching law prohibits state employers and schools from making hiring, admission, and scholarship decisions based on a person’s personal characteristics, like race, religion, and national origin. (The law specifically allows privately funded college scholarships based on personal characteristics.)

As part of these revisions to the original legislation, the law changes the criteria for the Next Generation Hoosier Minority Educators scholarship fund, replacing the requirement that a teacher candidate is Black or Hispanic with a requirement that they work in an underserved county — listed as Allen, Marion, Lake, St. Joseph, or Vanderburgh counties.

The scholarships, established in 2023, provide up to $10,000 per year of college for high-achieving students who commit to teaching in Indiana.

Sex ed: School must post material, teach consent

Under SEA 442, Indiana now requires schools to publicize more information about their human sexuality instruction, if they teach such courses at all.

Sex education is not required in any school other than instruction on HIV/AIDS, and under the new law, it remains optional.

But school boards in districts that choose to provide the instruction must post all of the relevant learning material online. The law states that schools can’t use any sex ed curriculum that hasn’t been approved by their school boards, which is true of curriculum on other topics, too.

The original Senate version of the bill went a step further and required school boards to also approve information about whether a male or female teacher would teach the course, and whether male and female students would be taught together.

The new law requires schools to put that information in the consent form sent to parents before sex ed instruction takes place.

Critics of the law pointed out that Indiana law already allows parents to review sex ed curriculum materials and opt their students out of any such instruction.

“Transparency is already the expectation,” said Cindy Long of the Indiana Association of School Principals at a hearing on the bill.

Supporters, however, said the law makes it easier for parents to find the information.

The law also says schools that do teach sex ed must show a medically accurate, age-appropriate presentation of fetal development as part of the course. They must also teach the importance of consent in sexual relationships.

Social-emotional learning not required for teacher training

HEA 1002 includes dozens of changes to education code that would reduce schools’ workload, said Rep. Bob Behning, the Republican chair of the House education committee.

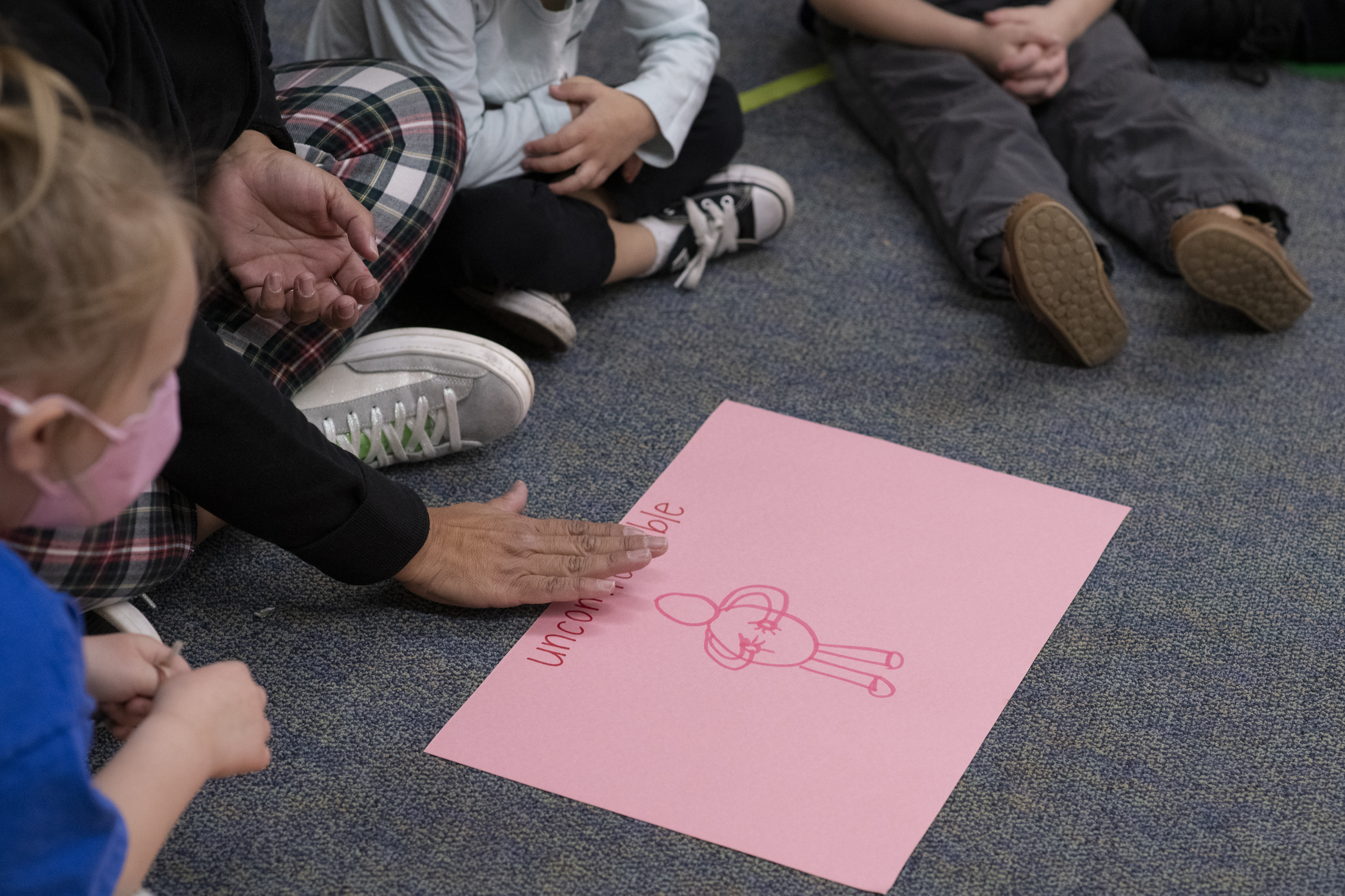

But one of the most controversial provisions drops state guidelines that teacher preparation programs include training on social-emotional learning, cultural competency, and restorative justice. These terms that have come under fire from conservative groups that say they teach children values that might be contrary to what they learn at home.

Originally, this language — added as a Senate amendment late into the legislative process — also stripped requirements related to positive behavioral intervention and trauma-informed care, too. But those provisions were restored by a conference committee led by Behning after public outcry.

Critics said practices targeted by the bill are considered best practices that reduce suspensions, expulsions, and behavioral incidents in classrooms, while supporting academic achievement.

Russ Skiba, an Indiana University professor emeritus whose research has found that Black students face higher rates of exclusionary discipline than white students, said changes in the way teachers learned about discipline practices in the early 2000s had a notable impact on reducing disparities. New federal and state guidelines did too, he said.

“The legislature has an important effect just in saying something ought to be focused on,” Skiba said, citing the science of reading as another example. “Suspensions and expulsions went down because of leadership from the top.”

Republican lawmakers defended the changes, saying that they didn’t ban any practices but only removed requirements.

Behning, who declined an interview about the law, notably authored a 2015 law that provided grants for schools to train teachers in alternative methods for student discipline, including “positive behavioral intervention and support, restorative practices, and social emotional learning.”

Lawmakers prioritize parental rights in student records law

Indiana lawmakers also this year passed a parental rights law with implications for schools.

SEA 143 says governmental entities may not “substantially burden a parent’s fundamental right to direct the upbringing, religious instruction, education; or health care” of their child, unless there is a compelling governmental interest.

Though the law had the support of many GOP lawmakers, some argued it could be interpreted to actually give the government more clearly defined rights over parents. Other critics raised concerns about the law’s treatment of minors’ constitutional rights.

The law specifies that schools cannot advise a child to withhold information from their parents, or deny parents access to information related to a child’s health care, or “social, emotional, and behavioral well-being.”

Though many of the examples offered in support of the law concerned state agencies like the Department of Child Services, some speakers at public testimony also wanted it to apply to when a student chooses to go by a different name or gender identity at school. A law passed in Indiana in 2023 already requires schools to notify parents when their students wish to make these changes.

At the same time, parents are prohibited from using the law to access a “medical treatment, service, or procedure” for the child that has been banned in Indiana, such as an abortion or gender-affirming care.

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.