For Newark’s class of 2020, senior year was memorable — but not in the way they expected.

The coronavirus pandemic forced them to spend the final months of their K-12 careers in quarantine, with text messages replacing the banter in hallways and cafeterias, and bedrooms standing in for classrooms. Prom and senior trips vanished, and Thursday’s citywide graduation ceremony will happen virtually, with students donning their gaps and gowns at home.

The future is equally uncertain. No one knows when college campuses will fully reopen, and when — or if — many jobs will return. Meanwhile, recent police killings of Black people have sparked a national reckoning with racism and police brutality that many students find upsetting but urgently needed.

The disruptions could have stopped the class of 2020 in their tracks. Instead, they took their finals, committed to colleges, and pressed on. Newark’s senior class is overflowing with stories of resilience and excellence. Here are four of them.

Taking risks to achieve her goals

When Melanie Gonzalez Castillo began her freshman year at Barringer High School, she had just arrived in the United States from Mexico. She didn’t speak English.

She enrolled in bilingual classes at Barringer, which has a large immigrant population. She was nervous about attempting to speak English in front of her new classmates. But she forced herself to try.

“I said that if I really wanted to learn, I just had to take some risks,” she said. “If people laugh at me, it doesn’t matter.”

No one laughed. Instead, her teachers and peers embraced her, and Gonzalez Castillo flourished. She managed Barringer’s soccer team and was elected president of the National Honor Society, twice. She became a dance leader and Sunday school teacher at her church, and tutored other students in math. She even joined a public speaking program.

This spring, she was admitted to her dream school: Villanova University.

“I came here focused on my goals,” said Gonzalez Castillo who lives with her sister, father, and stepmother in Newark while the rest of her family remains in Mexico. “I’m sacrificing so much time with my family, so it has to be worth it coming here and all the effort.”

On Thursday, she will give a recorded graduation speech as Barringer’s valedictorian. She plans to share a lesson she has learned during the presidency of Donald Trump, who has maligned Mexican immigrants.

“Ignorant misconceptions that people have about who you are don’t define your potential,” said Gonzalez Castillo, who is graduating with a 4.2 grade point average. “Go out and just take on the world.”

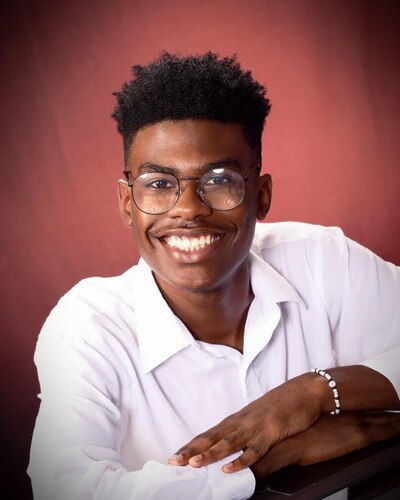

Pushing through adversity

The coronavirus has been cruel to Jamirr Baker, a star student at University High School.

The pandemic strained his family’s finances, forcing them to move in with his grandmother and aunt, and disrupted his mother’s job as a classroom aide. Now he and his sister help his mother with her new job delivering medicine for a pharmacy.

A math whiz, Baker thrived in school while also running track and competing on a step team. The pandemic separated him from his friends and teammates.

“I miss my team, I miss doing hurdles, I miss stepping,” he said. “Even teachers that are annoying — I miss them.”

But the worst news came last month. Baker had won a full scholarship to Holy Family College, a small school in Wisconsin with a program in actuarial science, which Baker plans to study. Then the college announced that the pandemic had dealt its budget a fatal blow: It will permanently close after this summer. In an instant, Baker’s college plans evaporated.

“I feel like everyone else knows where they’re going,” he said last week, “and I’m stuck.”

Yet like so many Newark students whose lives have been upended by the pandemic, Baker is pushing ahead. He’s reaching out to other colleges where he was accepted, including Howard University, to see if he can still enroll. And as he graduates with a 4.05 GPA, he’s holding fast to his dreams.

“It’s been put on pause because of the pandemic, but I feel like everything’s going to come together,” he said. “I really have hope for myself.”

Changing the system

Kutorkor Kotey was 11 years old when her family moved from Ghana to Newark. Her mother, who works in food service at a hospital, always made it clear why she took her two daughters to America.

“She brought us to this country for a reason: to excel,” Kotey said. “So that’s what I’m going to do.”

After attending Chancellor Avenue School, she was admitted to Bard High School Early College, a selective Newark magnet school. There she joined the National Honor Society, the multicultural club, the debate team, the Abbott Leadership Institute at Rutgers University-Newark, and the prestigious LEDA program, which aims to send high-achieving students from under-resourced backgrounds to top colleges. She also found time for an entrepreneurship program that helped her create a business selling ties, bowties, and suspenders made of Kente cloth.

Her hard work paid off: She will attend Princeton University this fall with a financial aid package covering all costs.

Still, the pandemic has created uncertainty. Princeton’s summer prep program for first-generation college students will occur online, making it harder to form friendships and adjust to campus life. And Kotey is still unsure whether fall classes will happen in person and if she’ll move into a dorm or stay home. “Everything is so weird right now,” she said.

Meanwhile, she has been closely following the worldwide protests that began with the killing of George Floyd, a black man in Minneapolis, by a white police officer. Having studied slavery and the civil rights and Black Power movements at Bard, she knows that state-sanctioned violence against Black people is older than America. But so, too, is the Black struggle for freedom.

“At the end of the day, the system was never meant for us,” she said. “The power lies in the hands of white men — that’s what needs to change.”

Embracing positivity

Vashu Patel still cringes at the memory of freshman year history class.

He was new to West Side High School and to the country, his family having recently emigrated from Kenya. Now he was straining to understand world history as taught from an American perspective in an American accent.

“That first test was obviously a nightmare,” he said. “I got an F.”

Things quickly turned around. He got the hang of American schooling and started racking up A’s. He joined the soccer and bowling teams and an NGO club, which recently hosted a video chat with nonprofit workers in Somalia. He felt his “stress just disappear” during “Lights On,” West Side’s celebrated evening program that gives students a safe space for sports, art, and socializing. And his dry sense of humor won him plenty of friends.

“I’ve not seen a lot of bad people in this country or in my school,” he said. “Except maybe the freshmen.”

In the fall, he’ll attend the New Jersey Institute of Technology, where his tuition is fully covered. He plans to study computer science after an advanced manufacturing class at West Side sparked his interest in coding. He expects his first semester will be online, “but then I will get out of this lockdown and start going to college like a real man,” he insisted.

Patel’s father works in a duty-free shop at the Newark airport and his mother runs their home. They recently learned that Patel is West Side’s valedictorian. They were overjoyed, if also a little shocked.

“This son who couldn’t get a 50 in math in Kenya suddenly becomes a valedictorian here,” said Patel, who earned a 4.4 cumulative GPA. “They were really proud.”

In light of the pandemic and the protests, his graduation speech will focus on “embracing positivity.”

“Yes, there will be tough times,” he said. “But they’ll go away soon.”