New York City families aren’t expected to find out until the end of August how many days a week their schools will provide in-person learning.

The number of days students will report for in-person instruction will depend on their enrollment and building capacity, as most schools will only be able to have about nine to 12 children in a class at a time since students are supposed to keep six feet apart.

Schools will likely struggle with staffing since smaller classes require more teachers — an especially tricky proposition given that school budgets are constricting. In some ways, schools that are among the most popular — and therefore overcrowded — might become victims of their own success and end up with the least amount of in-person instructional time. Other areas of the city that struggle with overcrowding, including many immigrant communities like Sunset Park and Flushing, might also face a tight squeeze.

The education department is asking principals, in consultation with their school communities, to pick among different scheduling options that would place most students inside buildings anywhere from one to three days a week. With more than 1,800 schools, though, the education department will allow school leaders to propose models that work better for their buildings, number of students, staffing realities, and teaching approach.

Ultimately, who goes to class, and how often, will also depend on how many students and educators want to return to in-person learning. Families can opt for fully remote instruction, and teachers and school leaders with health concerns can apply for permission to continue working from home.

But all of these moving parts could make it extremely difficult for schools to plan. Families, for instance, have between July 15 and Aug. 7 to enroll for full time remote learning — which is before they’ll know what their school’s schedule will be.

Teachers with health concerns who don’t want to report back to buildings can start applying for accommodations on July 15, and education department officials will start sharing those numbers with schools on July 23, union officials said. That could make it difficult for schools to plan their schedules, which are initially due on July 23, and must be finalized by Aug. 14.

Classes are scheduled to start Sept. 10.

Many other details remain murky about reopening plans. The education department did not discuss whether educators would be covering the same material with the different groups of students each week during in-person learning and what materials students would use during the remote learning days. Nor do city officials have a child care plan for working parents — including school staff — who are unable to stay home with their children on days they’re not attending schools.

“Working families who have multiple children attending different schools — or maybe even different grades at the same school — will be forced into an impossible juggling act,” Kim Sweet, director of the nonprofit Advocates for Children, said in a statement. “Schooling is inextricably intertwined with child care, and the two systems must be looked at together — not in isolation or as an afterthought.”

Christine Feliciano Barrett, an English teacher at Queens High School of Teaching in Bellerose, said she is eager to get back into a classroom, but still has a mountain of questions about how teachers will be expected to juggle in-person instruction, remote classes, and their own child care issues. She has four daughters who attend school on Long Island.

Barrett expects to have almost 200 seniors on her own roster next year, and the logistics of meeting both in class and online are daunting. Her small school doesn’t even have space for individual desks in most rooms, and instead seats students in groups, so it’s unclear how they’ll fit in socially distanced students.

“I’m open to going back in September. I’m not against it,” she said. “It’s just a lot more questions than answers at this point, and that’s frustrating because we have, what, eight more weeks?”

One big caveat: The city’s reopening plans must win state approval, and Gov. Andrew Cuomo said it was too early to confirm whether schools will open in the fall. The teachers union also said without federal funding to cover the costs of enhanced cleaning and help schools meet other protocols, buildings won’t be able to reopen.

The city outlined these three models for elementary, middle and high school — plus two options for schools that serve students with disabilities.

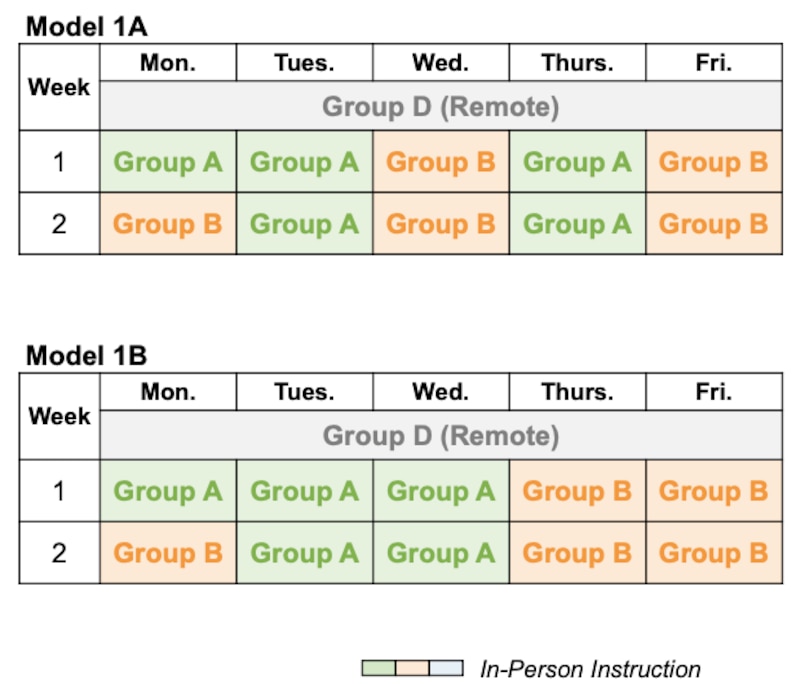

For schools that can host at least 50% of their students at a given time, students will be divided into two groups.

Each would go to school twice a week on alternating days, or with two days in a row. For example, one group would attend on Tuesdays and Thursdays, with the other going Wednesday and Fridays. Or, one cohort would attend every Tuesday and Wednesday, and another would attend every Thursday and Friday.

Each group would go to class for one additional day every other week by alternating on Mondays.

This would equal a total of five days of in-person instruction and five days of remote learning every two weeks.

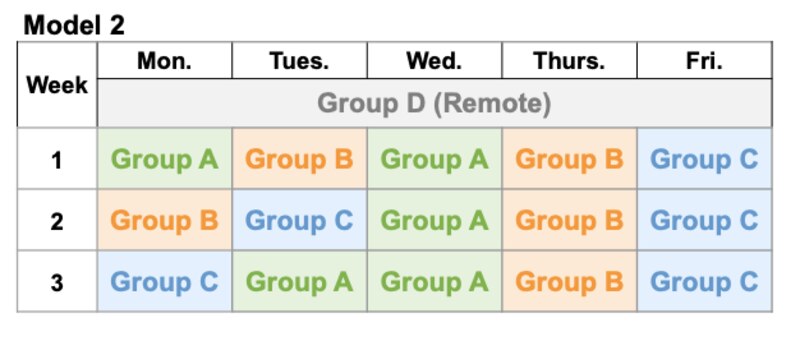

For schools able to hold about a third of their students at a given time, children would be divided into three groups.

Each group would have one day a week they attend consistently. Every two weeks, each group would attend a second day, but the third week, would attend only one day.

For example, a student on a Thursday schedule, would attend Monday and Thursday one week, Tuesday and Thursday the next, and just Thursday the week after that.

This amounts to a total of five days of in-person learning and 10 days of remote learning every three weeks.

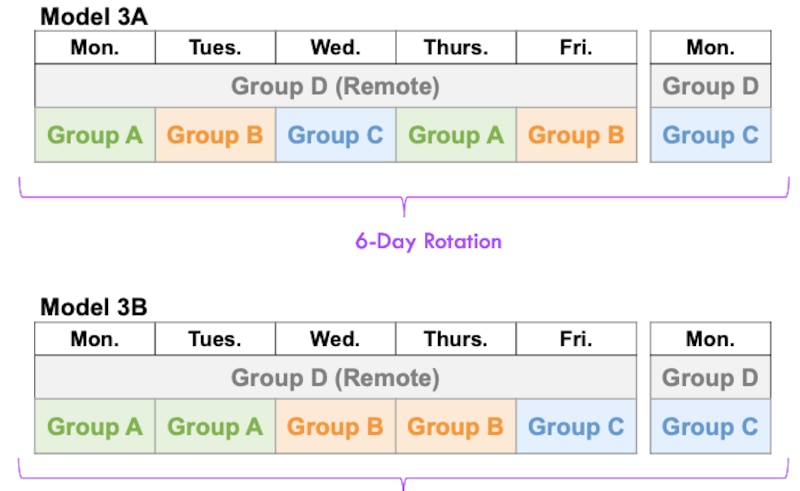

Here’s a second option for schools that can only fit about a third of their students at a time.

Students would again be divided into three groups that would have five in-person learning days every three weeks — but with a different pattern than the previous option.

In this model, students would attend school twice every six days, while doing remote learning for the other four days. For instance, one group of students might attend on Monday and Tuesday one week, then the following week on Wednesday and Thursday, then only on Friday, the week after that.

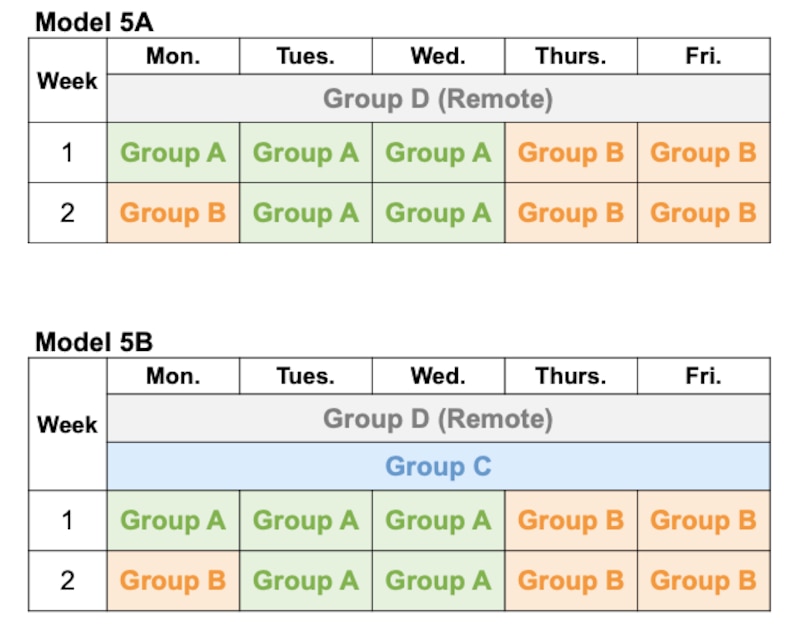

District 75 schools could alternate weeks.

District 75 schools serve children with the most complex disabilities. There are two different schedules proposed for these schools.

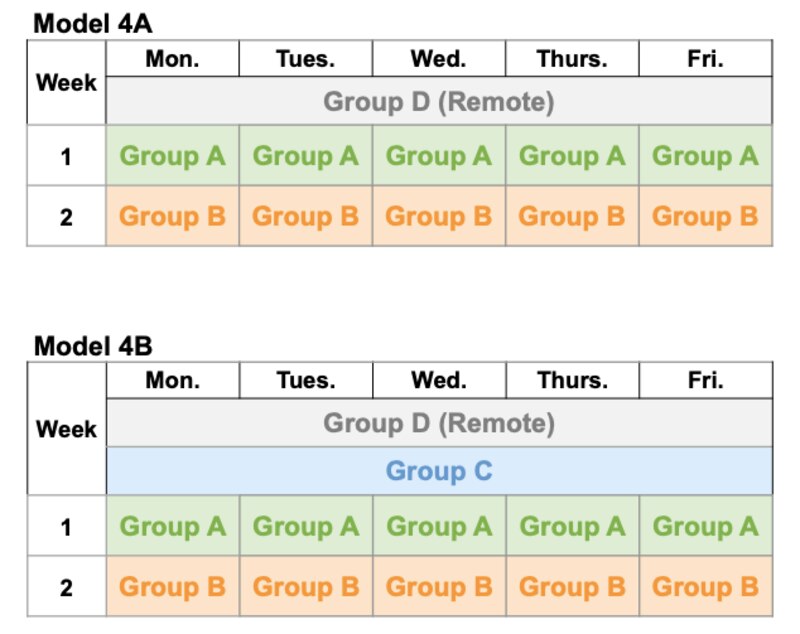

One model would break students into two groups, each alternating full weeks in school.

A variation of this model would include three groups of students, with one group attending school full-time. The other two other groups would continue to alternate one full week in-person and one one week of full time remote learning.

Or, District 75 schools could assign students to consistent days in-person, with alternating Mondays.

The second model available for District 75 schools would alternate groups of students on consistent days, while rotating Mondays — similar to the model for other elementary, middle and high schools.

For example, one group would attend on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, and another would go to class in-person on Thursdays and Fridays. Each group would be in school for a total of five days and doing remote learning for five days every two weeks.

A variation of this schedule would allow for a third group of students to attend class daily, while the other two groups would continue to rotate Mondays and attend school on their consecutive assigned days.