Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

Until her junior year, Brooklyn high school student Afag Sidahmed never enjoyed history classes.

“I was so sick of learning about Europeans,” she said. Her courses rarely focused on Black history, with the exception of Martin Luther King Jr.

But this year, a new course offered at her school, the Urban Assembly Institute of Math and Science for Young Women, has changed her feelings about the subject.

“When I heard about AP African American Studies — and the word African was in there — I was like, ‘Wow, I am taking this class,’” she said.

In 2022, the College Board rolled out its first Advanced Placement course in African American studies through a pilot program at 60 schools across the country. This year, the program expanded to nearly 700 high schools nationwide, with 59 of the city’s schools offering the course locally.

Next year, the course will officially launch, allowing any high schools to offer it. Nearly 160 additional high schools in New York City have already expressed interest in the course, though that number will likely shift as schools develop their plans for the next school year, officials said.

The materials covered in the class have spurred controversy in some states. Last year, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said the state’s schools wouldn’t teach the class and alleged it violated a state law that restricts how race and racism are taught. And when the College Board later released a revised curriculum that had removed much of the criticized content, others protested the organization had buckled under political pressure and watered down the course.

Still, despite being enmeshed in a national political dispute, educators in the city and across the country have emphasized the vital role the class can play in schools and the value it can bring to students.

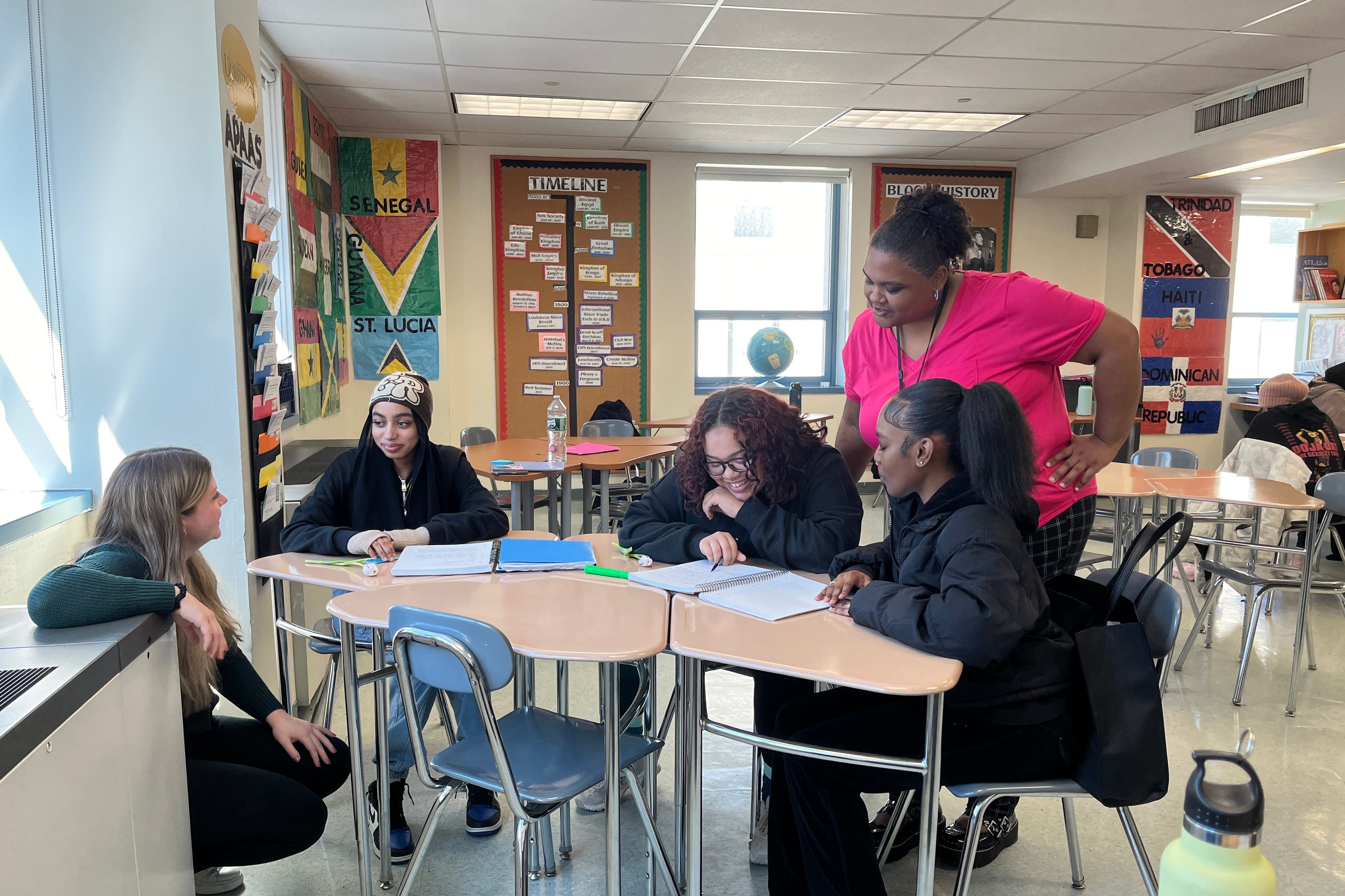

At the Institute of Math and Science, 32 students across two classes are taking the course, both taught by teachers Kelly Preston and Martine Mercier. Inside their fifth-floor classroom, the walls are decorated with a timeline of Black history that spans thousands of years, and the flags of nations in Africa and the Caribbean. A class constitution encourages students to ask questions, value each other’s opinions, and express any disagreements respectfully.

For Preston and Mercier, the focus of the class has been on student-led discussions and engagement. Typical lessons rely almost entirely on students analyzing primary sources in small groups, instead of more-traditional lectures.

“Kids should be active agents of learning,” Preston said. “They’re not passive absorbers taking in what we tell them. They can create that understanding for themselves, and we want them to feel that agency, and feel empowered in their educational experience.”

Students look to primary sources

In one February class, Preston and Mercier used a hypothetical scenario to segue into a lesson on the Great Migration, a period in the 20th century when millions of Black people moved from the rural South to urban areas in other parts of the country.

Students considered what conditions would prompt them to leave their school for another — whether they’d do so based solely on negative treatment, or if a viable alternative school would be needed to pursue a new environment.

Afterwards, students turned to historical documents, discussing in groups of three or four. Preston and Mercier walked between tables, listening in, posing additional questions, and urging students to explain the reasons for their answers.

Mercier said she and Preston are prioritizing “having the students not always look to us to affirm whether they’re correct or not, but look to each other and look to other sources to affirm what they’re thinking.”

Alizett Tavarez, an 11th grader at the school, explained how she inferred the meaning of the Great Migration through clues from paintings by Jacob Lawrence, a 20th century American painter whose work documented aspects of the Black experience.

“The first thing that caught my eye was how in each of the paintings they have signs that show Chicago, New York, and St. Louis,” she said. “The next picture said tickets, tickets, tickets. It made me assume they were traveling north.”

During the discussion, students often turned to other figures and moments in Black history, drawing connections to Harriet Tubman, Black Wall Street, the Harlem Renaissance, and more.

When Preston and Mercier asked students to consider why so many individuals chose to migrate north, one student spoke up.

“For real freedom,” said Esha Azam, a 10th grader. “Because after slavery ended, the South created the Black Codes, literacy tests, and Jim Crow laws,” she added, referring to various laws that states adopted to restrict the rights of Black Americans to vote or own property, for example, and to enforce racial segregation.

More powerful than just an exam

The AP course pilot is one of several ways New York City educators are working to broaden the scope of how Black history is taught in schools.

Sonya Douglass, a professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College and director of the Black Education Research Collective, helped develop a pre-K-12 Black studies curriculum that has been offered recently across roughly 10 districts as part of a pilot program. Douglass and others worked to develop the curriculum with the Education Equity Action Plan Coalition, a group of educators, nonprofits, and government leaders.

“So far, we have seen a lot of enthusiasm among educators, community members, and students — the older ones of which say, ‘This is long overdue,’” she said. “What we’re really excited about at the K-12 level is basically generations of young people who will have access to this information.”

The AP African American studies course has prompted further discussion and excitement among local communities, Douglass said. For educators who are tackling the material for the first time next year, it’s critical to approach it with “cultural humility,” she noted.

“No matter your background, even if you are of African descent, many of us don’t know this history,” she said. “Just taking that learner’s stance is so important.”

Preston and Mercier have also shared advice for educators in recent months, speaking about their experience leading the class on a local panel with other Brooklyn schools, and at the national College Board Forum in November.

The two educators suggest teachers who are new to the course embrace the work and trust their students.

“It’s not easy to roll out a brand new course — especially one that centers stories and narratives that haven’t always been highlighted,” Preston said. “It’s a lot of learning and unlearning you’ll need to do. … But really, trust the kids. The kids can do this. They can interrogate sources. They can create understanding for themselves. They can have meaningful, effective conversations.

“You just have to figure out how to support them in doing it,” she added.

Kiri Soares, principal of the Institute of Math and Science, praised Preston and Mercier for developing a successful model for the course in its first year at the school. But Soares noted she’s worried fewer students will be able to take the course if it isn’t able to count as a U.S. history credit toward a student’s graduation requirements. (The city’s Education Department said the class is credited as a humanities elective.)

Soares’ hopes for the class hinge less on the results of the AP exam in May — which will be offered for the first time this year — and more on what students can gain from the content covered within it.

“My goal in this course in particular is to have them see themselves written into history,” she said. “That is a disruptor to the history that their families have had, and it’s pretty amazing and more powerful” than a top score on an exam.

For some students at the school, the class has accomplished just that.

“It always ties back somehow to your roots,” Alizett said. “You always learn more than you expect.”

“You definitely learn about your ethnicity in the classroom,” added Amna Sobahi, an 11th grader. “Like I don’t even need a DNA test anymore — I have Ms. Kelly.”

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.