Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to keep up with NYC’s public schools.

A tentative budget agreement announced on Friday will see additional dollars funneled to New York City’s free preschool program for 3-year-olds, but falls short of the full restoration sought by child care advocates.

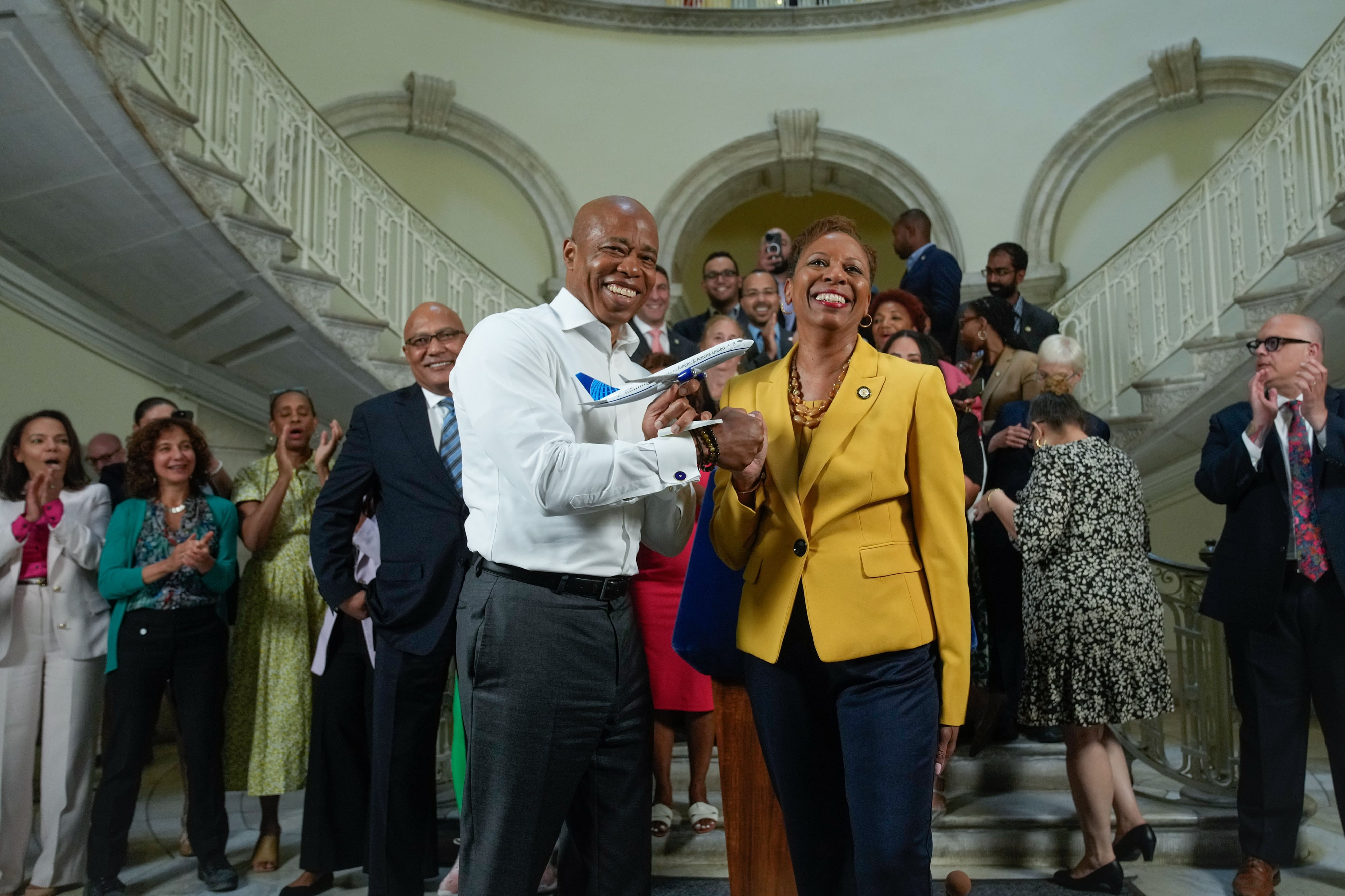

The deal on a total $112.4 billion city budget comes just days shy of the July 1 deadline and follows months of negotiations between City Council and Mayor Eric Adams’ administration. The turbulent budget process has seen Adams direct several rounds of cuts and restorations to the Education Department’s budget, as New York City braces for the expiration of billions of dollars of one-time federal pandemic relief money.

Officials did not say how much funding in total would be allocated to the city’s Education Department during the Friday announcement. In April, the mayor’s proposal devoted $32.2 billion to the city’s schools. That proposal represented a 2.4%, or $808 million, decline in funding for the next fiscal year.

Still, the city’s contribution to the Education Department’s budget — which also includes federal and state dollars — is set to rise by at least $1.6 billion. However, that additional funding isn’t enough to offset the $2.4 billion drop in federal funds.

The final budget represents a significant win for advocates who feared City Hall would institute deep spending reductions on top of expiring federal aid. But in the end, Adams dialed back the worst of the cuts and found hundreds of millions in city money to replace federal dollars.

“We began the year sounding the alarm,” wrote Kim Sweet, the executive director of Advocates for Children, an organization that represents high-need families and pushed hard for funding restorations. “We appreciate that the budget deal includes more than $600 million for critical education initiatives currently supported with expiring federal funds.”

Preschool programs see partial funding restoration

The budget agreement will see an additional $20 million invested in the city’s program for 3-year-olds to add seats for families without 3-K placements, as well as an additional $25 million — that will join an existing $15 million, for a total of $40 million — to expand days and hours at more preschool programs and help fill vacant 3-K and pre-K seats, according to city officials.

It will also add $30 million to increase funding for preschool special education seats. Children with disabilities have languished without placements despite a vow from Adams to provide universal access, as required by law. Adams had already agreed to replace $56 million in federal funding that he had previously directed to stabilize the preschool special education system, and another $25 million to create more seats and help provide other services like speech therapy.

City officials said the additional funding would guarantee every child with a disability a seat, though it remains to be seen if that promise will translate into reality — as the shortage of seats and related services has persisted for many years.

Under the budget agreement, a working group will also seek to develop reforms to the early childhood system, officials said.

The city budget “balances fiscal responsibility and taking care of working class New Yorkers,” the mayor said.

But the budget agreement won’t fully reverse the cuts that early childhood programs have faced this year. The city’s preschool system has taken center stage in budget negotiations, with council members and advocates pushing for further investments.

Adams put forward a plan in April that would replace $92 million of expiring federal funding for 3-K with city and state funds, but that plan did not restore a separate $170 million of city funding that was previously cut from early childhood programs. The mayor repeatedly argued the cuts were necessary because the city was wasting money on thousands of unfilled preschool seats.

Though the council initially sought a full restoration of the $170 million cut, Finance Committee Chair Justin Brannan acknowledged on Friday that “some of the numbers are aspirational,” conceding that vacant seats were an issue and the early childhood system needed deeper reforms.

“We needed to do more than just restore those cuts,” he said. “We needed to be smart about it, because you have a system right now that’s got a wait list and lots of vacant seats, so it needs reform … just throwing money at the problem wasn’t going to fix it.”

Despite cuts to the early childhood system, the mayor has promised every family who desires a seat in the city’s prekindergarten and 3-K system will receive one.

Still, last month, some families said they didn’t receive a spot in any program they applied to — or were admitted to a program that was far from home, posing severe logistical challenges. Officials later said many seats remained open and the city would work with families who were not initially admitted to find nearby open seats.

Council Speaker Adrienne Adams stressed that offering a 3-K seat to every family will require more funding from state sources. “We cannot afford to do this work alone,” she said.

Despite added funding, concerns over preschool, other programs persist

The looming fiscal cliff has also placed the fate of several other education programs in limbo. Those include roughly 400 contracted school nurses — some of whom provide care at buildings that previously lacked a school nurse — as well as Promise NYC, a program that offers subsidized child care for undocumented families.

The budget deal will see $25 million invested in Promise NYC, a roughly $9 million increase, though it was not immediately clear on Friday whether it would provide funding for school nurses.

Though child care advocates were pleased to see some funding restored, many remained concerned over the state of the city’s early childhood system. The sector has struggled under Adams, faced with payment delays that have hobbled many programs. Additionally, the city has not yet solved the longstanding salary disparity issue, where teachers in privately run but publicly funded pre-K programs earn significantly less than their counterparts teacher 3- and 4-year-olds in public school programs.

“The early childhood education system in New York City is complicated — the needs of children and families are not,” said Nora Moran, the director of policy and advocacy at United Neighborhood Houses. “We continue our fight to ensure there is a seat for every young New Yorker in our early childhood education system, and we urge the City to invest in our center-based early childhood workforce by bringing them into parity with their public school counterparts working the same jobs with the same credentials — something this budget fails to address.”

Budget process marked by repeated cuts and restorations

In recent months, the mayor has announced a series of budget cuts and investments as the city worked to fill sizable gaps left by the expiring federal relief funds — further clouding the already complicated process through which the city determines its more than $112 billion budget.

In November, the Education Department cut roughly $550 million from its budget as Adams directed a sweeping round of citywide reductions. Another round of cuts in January slashed an additional $100 million from the budget, though those cuts were less severe than had been previously anticipated.

Separately, the Adams administration has worked to find city and state dollars to replace funding for programs currently propped up by federal funds.

In April, the mayor announced the city would use more than $500 million of city and state funds to plug holes in the Education Department budget created by expiring COVID relief funds. And earlier this month, the mayor announced an additional $127 million would help reverse budget cuts at some schools that have faced enrollment losses, fund restorative justice programs that encourage peer mediation and other non-punitive methods of resolving conflicts, and restore hours for the city’s popular Summer Rising program.

Though some education programs that were previously propped up by federal funding will have dedicated city funds that persist beyond the next fiscal year, others — like a roughly $92 million expansion of 3-K, the Learning To Work program that supports students at risk of dropping out, and the Project Pivot program that partners schools with community organizations to reduce violence — will need to be renegotiated during the next budget process, teeing up future education funding fights.

City Council is expected to formally vote on the budget deal on Sunday.

Michael Elsen-Rooney contributed reporting.

Julian Shen-Berro is a reporter covering New York City. Contact him at jshen-berro@chalkbeat.org.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.