This story was originally published on Sept. 16 by THE CITY. Sign up here to get the latest stories from THE CITY delivered to you each morning.

The number of homeless youth who were denied shelter in the city shot up this year, with more than 1,100 young people sent back to the streets between January and July of 2024 — a historically high number driven by the asylum-seeker crisis, advocates say.

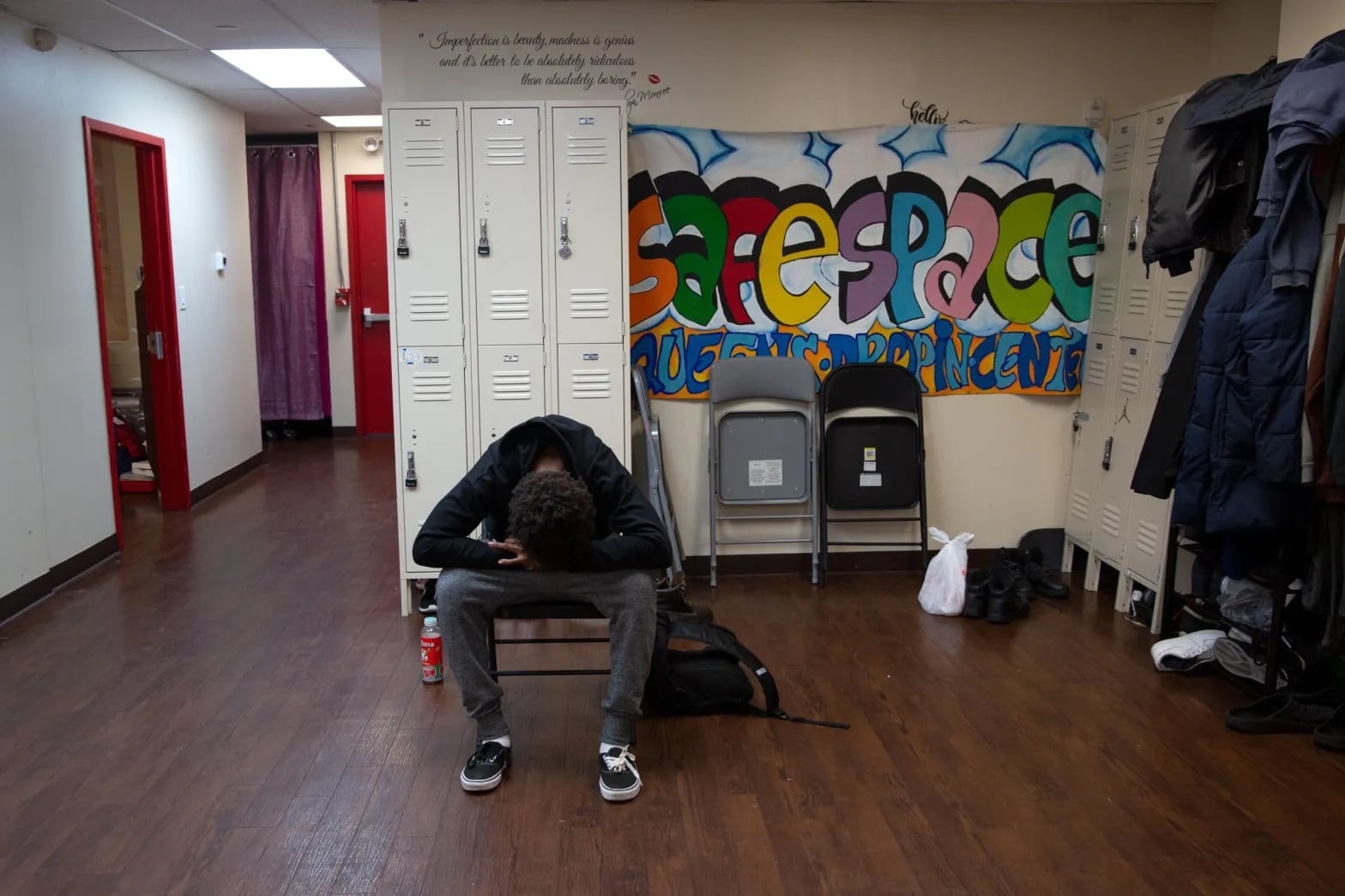

New data, released Thursday by the Department of Youth and Community Development, shows a steady increase in “youth not placed,” meaning shelters and drop-in centers operating under city-funded contracts couldn’t locate a bed for runaway and homeless youth between the ages of 16 and 24.

The statistics have grown steadily more dire.

In the first six months of the year, 1,127 young people could not be placed in any beds, data shows, without anyone declining a bed. That’s up from the 234 young adults who requested shelter and were not placed between July 1 and Dec. 31, 2023, including four who declined it.

In the first six months of 2023, only nine young adults were denied beds, including two who declined shelter.

There are 789 available beds through DYCD-funded runaway and homeless youth providers, and 338 separate beds for homeless young adults, according to the city.

Mark Zustovich, a spokesperson for DYCD, noted in a statement that the agency helped more than 500 young adults move into their own homes, although he did not specifiy during what time frame.

“While this report indicates that DYCD’s runaway and homeless youth system was fully utilized at the beginning of the calendar year, in the final two months of the reporting period, the number of young people not able to access an RHY youth shelter bed dropped significantly,” he said in a statement.

The city figures show a decline from a high of 363 young people turned away in January down to 54 in May and 58 in June.

While noting that the city does not track immigration status of shelter youth, he said, “the influx of asylum seekers contributed to the increased demand.”

Zustovich also said that “most” people unable to access youth beds were adults who have access to the city’s main homeless shelter system.

“DYCD providers continue to connect all young people to available resources or refer them to other programs so they get the critical services they need,” he added.

The department produces this report twice a year by law, detailing the age, gender and sexual orientation, if known, of every young person turned away and from a city-funded site.

The sharp increase shows there is demand for shelters designed to house youth, which are often in smaller settings with more services even for those eligible to enter an adult shelter, according to advocates.

The data contrasts with Mayor Eric Adams’ assertion that nobody — including asylum seekers — is going without shelter. The report does not say where they believe the young people go after being turned away from shelter.

“Contrary to what the mayor is saying — numbers going down, people not being regulated to the streets — that statement is clearly not holding true for young people,” Jamie Powlovich, the former executive director of Coalition for Homeless Youth, told THE CITY.

Settlement oversight expired

In 2020, a legal settlement by a federal judge guaranteed 16- and 17-year-olds who sought shelter would get beds at age-appropriate city facilities. The settlement came following a class action lawsuit filed a decade ago by the Legal Aid Society, which sought to get young people the same right to shelter as adults.

The settlement, however, didn’t extend to 18- to 24-year-olds, who, the report shows, represent a large share of those turned away from any shelter beds.

The monitoring period for that settlement expired at the end of 2023, which may have also caused the increase in street homeless, noted Theresa Moser from Legal Aid Society’s Juvenile Rights Project. It’s likely a combination of that expiration and an overall increase in youth homelessness and asylum seekers pushed the numbers of people turned away from shelter up, she said.

“We do see a lot more asylum seekers who are finding their way to DYCD programs and there may be an increase in other young people who are also seeking that program,” she said.

Eight months after being sworn into office in 2022, Adams released a plan to end youth homelessness boosted by a $15 million federal grant to make it easier for homeless youth to find homes.

The administration committed to fund a new street outreach program targeted toward youth, the creation of 20 jobs for youth who experienced homelessness, and 102 new units of “rapid rehousing” for youth and young adults, according to the Mayor’s Office.

“New York City has always been a place for those seeking refuge and acceptance, including young people, many of whom are fighting discrimination, bigotry, or family rejection,” he said in August 2022.

“To every young person in our city: We have your back, we’re looking out for you, and the entire city is ready to help you chart your future.”Other efforts to make it easier for young people to find permanent housing, however, have been squelched by the Adams administration, including a City Council measure that would have made rent-subsidy vouchers available to residents in the youth shelter system.

The City Council and Legal Aid sued the Adams administration to implement the bills, but last month a judge sided with the mayor’s team.