Sign up for Chalkbeat New York’s free daily newsletter to get essential news about NYC’s public schools delivered to your inbox.

New York City students in juvenile detention often show up with deep learning challenges and frequently don’t get the support they need to catch up, according to a new analysis of city data.

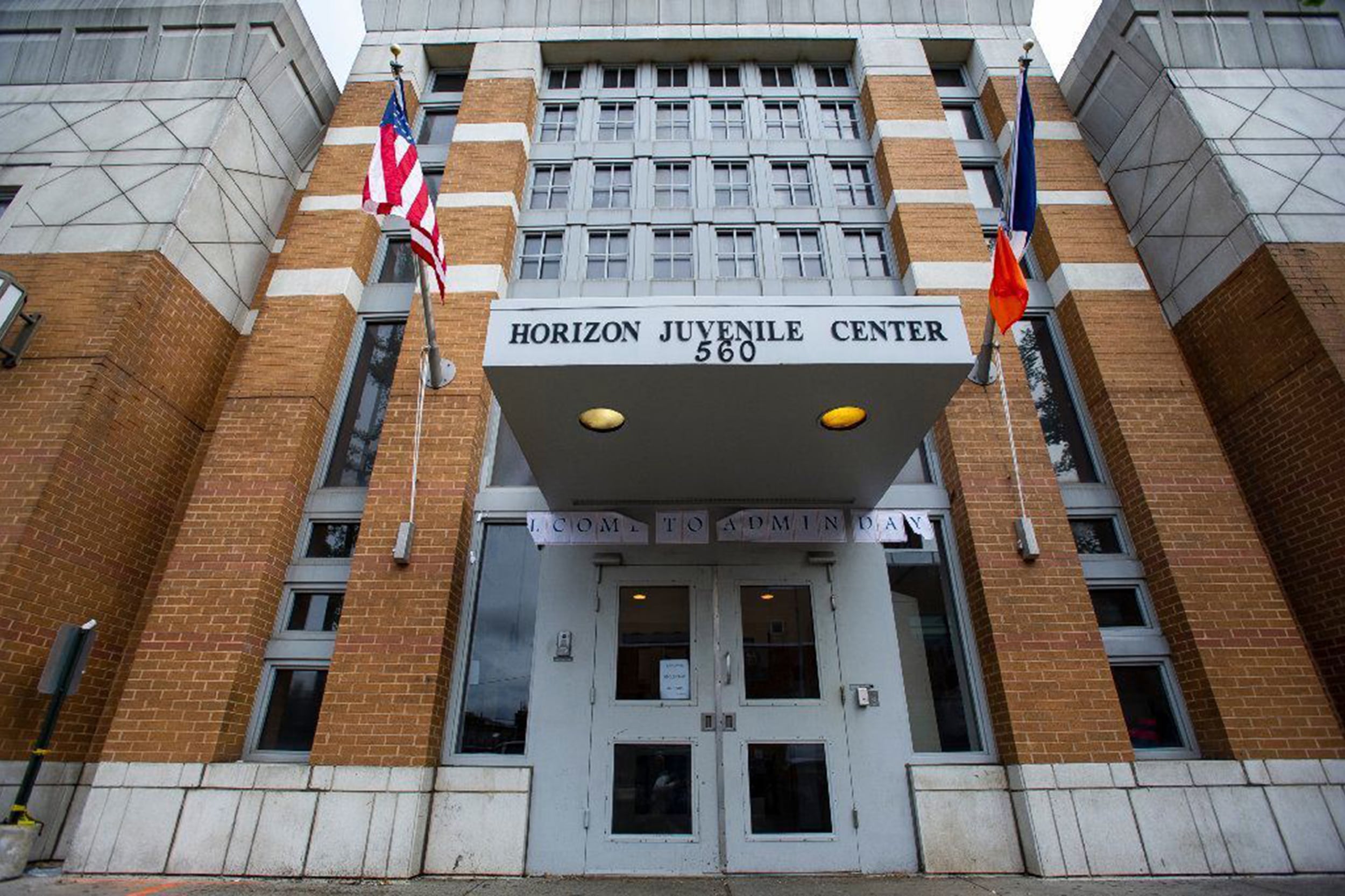

Court-involved youth held in juvenile detention facilities and group homes managed by the Administration for Children’s Services, the city’s child welfare agency, are entitled to schooling through an Education Department program called Passages Academy.

Those programs tend to receive little public scrutiny, though they serve some of the city’s most vulnerable students. In 2023, City Council passed a law requiring officials to release a trove of data about the program. A report released Monday by Advocates for Children, a group that helps families navigate the school system, includes the first detailed analysis.

“Too often these young people continue to struggle to access the educational services and supports that could help them succeed, both while in detention or placement and after returning home,” the report says.

Here are five takeaways from the report:

Black boys are overrepresented, and so are students with emotional disabilities

Over the past two school years, 1,850 students enrolled in Passages Academy. More than 60% were Black, more than 92% were boys, and virtually all were from low-income families, according to an enrollment snapshots from October 2023 and 2024. (About a quarter of all children in middle and high school are Black and 78% come from low-income families.)

Nearly half of all students in Passages had a disability, more than twice the rate across the school system.

Students in juvenile detention were also far more likely to be classified with an emotional disability: 18% of students enrolled at Passages received that classification compared with just 1% for students in middle and high schools across the system, according to the report.

Students arrive with significant learning challenges

When students arrive in juvenile detention, they are often far behind their peers in reading and math. On average, students at Passages who were assessed in reading scored in the 10th percentile in 2023-24 and the 18th percentile the following school year. Math scores were similarly low.

Education Department officials said they’ve expanded efforts to identify students with reading challenges, such as dyslexia. Teachers across the program are receiving additional training to catch students up.

They don’t always get the extra help they’re entitled to

Students with disabilities are entitled to new learning plans that spell out what services they will receive while within 30 days of arriving at a Passages program. But officials failed to provide the plans on time for nearly 17% of eligible students, according to figures for the last two school years.

The Education Department did not provide statistics on what percentage of required special education services were actually delivered, even though that data was required to be released under the City Council law. Officials said it is difficult to collect those figures because students move in and out of the program frequently.

English learners, a group that represents about 12% of Passages students, also struggled to access the support they need. Nearly a quarter of those students received no English as a new language instruction while they were in custody during the past two years, the report found.

The report suggests that some students in secure detention facilities are not always given access to instruction. In 2023, Gothamist reported that some classrooms were sometimes used as cells or for sleeping accommodations.

“If they’re not actually getting to Passages then they’re not getting an education — period,” said Rohini Singh, director of the school justice project at Advocates for Children and a co-author of the report.

Education Department officials acknowledged there are gaps in services and said they are launching afterschool and Saturday programs that include speech therapy and small-group reading instruction at two Passages sites beginning next month.

“We appreciate the advocacy from our partners with Advocates for Children, and we take these concerns extremely seriously,” Education Department spokesperson Onika Richards wrote in an email.

A spokesperson for the Administration for Children’s Services said the agency helps coordinate tutoring. They also help students earn high school equivalency diplomas or complete college coursework, as some people in secure detention are 18 or over and not legally required to attend school.

Once released, students often struggle to reconnect with school

The report details multiple examples of families receiving little or inadequate support enrolling in school once their child was released from detention.

After one 14-year-old student was discharged, his mother visited a nearby school in the Bronx to enroll him. But because her son was not physically with her, the school refused. The teen was not allowed to leave their home at the time under the terms of his release.

“The failure to connect [the student] and his mother with any resources that could assist with the transition back to school upon his release placed them in an impossible situation,” according to the report.

Even when students do enroll in traditional schools once they’re released, their attendance rates are often abysmal. More than half of students discharged over the last two years were absent on at least half of all school days in the two months after they returned to a traditional school. (Those figures only include students who transitioned to city public schools and stayed for at least 10 days.)

Richards said the Education Department is working “to ensure court-involved youth receive the comprehensive transition support they deserve.”

Beefing up support could help make a dent, advocates say

Advocates urged the Education Department to take several steps to prevent students from getting tangled up in the court system in the first place, including expanded mental health and special education support.

And they called on the city to beef up transition services to help families enroll in schools once their children are released from detention. Singh noted that many students might be good candidates for transfer schools, which generally enroll students who are older and behind in credits, though it can be challenging for families to navigate that enrollment process.

More broadly, she said the city must expand access to services for students while they are enrolled at Passages, especially among students with disabilities.

“Our hope,” Singh added, “is the administration will take a closer look at these students and make sure they receive interventions while they’re in custody.”

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering NYC public schools. Contact Alex at azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.